This post continues with a discussion (begun here) of Nancy Fraser’s analysis,

I like to think in images so have prepared a few for this post. If you find them confusing then stick with the words. If they’re confusing then read the original article linked above.

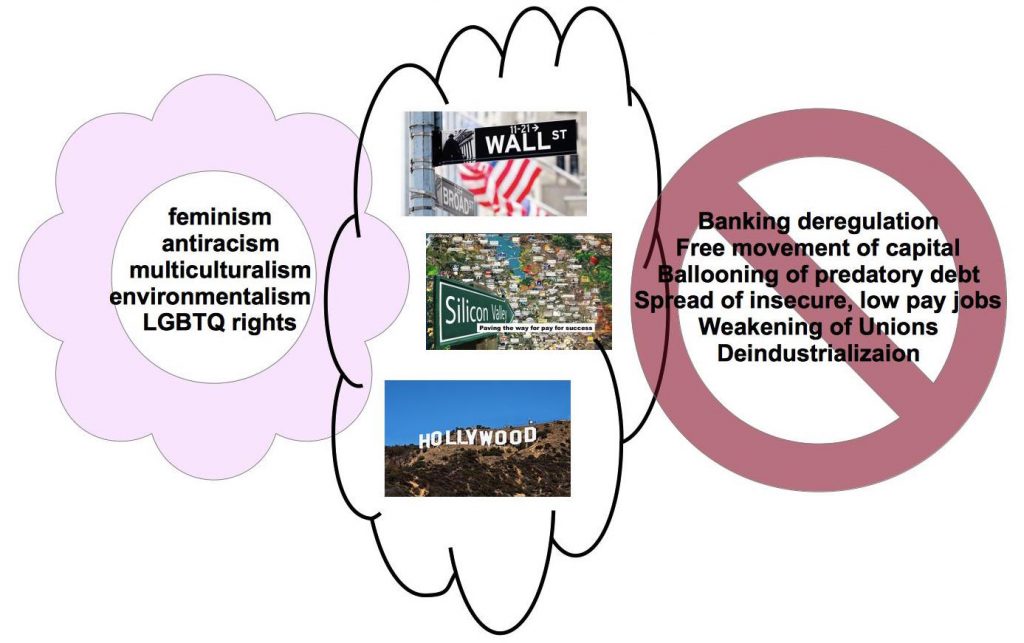

Here is the essence of the previous post. The hegemon of the “progressive neoliberal bloc” is the “most dynamic, high-end “symbolic” and financial sectors of the U.S. economy”. It maintains its power by persuading the lower and middle classes that its values are the “common sense” view of the world. Gender and racial equality, for example, are promised to become the conditions for economic fairness and prosperity for all. That this message is a myth hiding a darker reality for most people was explained in the previous post.

This segment of economic rulers promoted the values of feminism, antiracism, etc, promising a more prosperous society for all but in fact delivering what was the inevitable result of their economic goals. They promised that progressive values were in sync with the new economy of deregulation and that everyone would prosper from deregulation all round. See the previous post for details. The reality was different, though, as per the diagram that shows the “values of recognition” on the left and the results of the other set of values, those of “distribution of wealth” on the right.

“The Progressive Liberals”

These were the winners under first Reagan, then especially under Clinton and Obama.

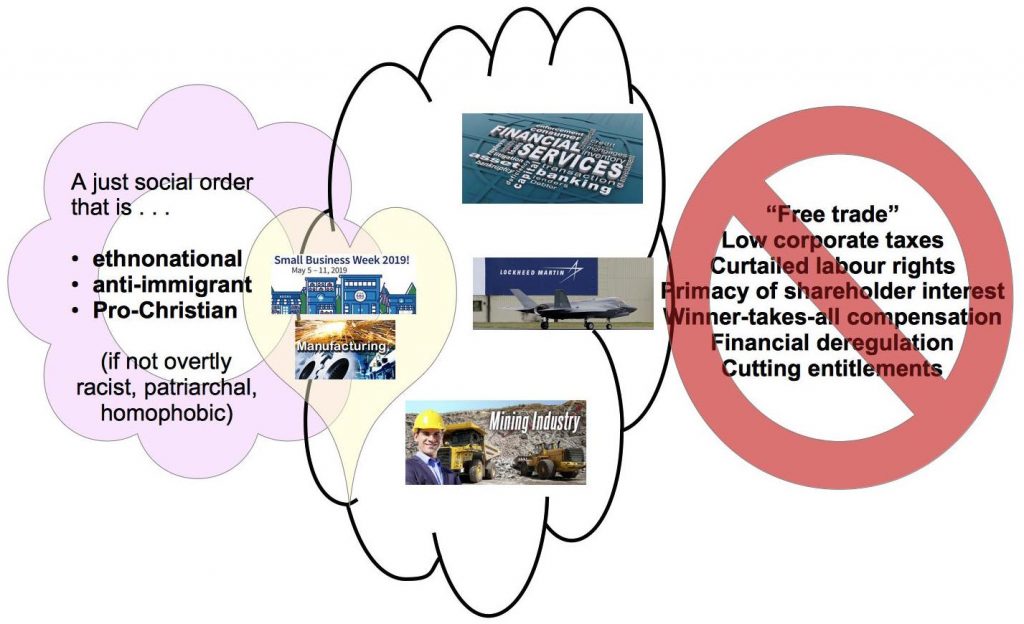

But there is always a but. Another sector of economic rulers, those who found the Republican Party to be more supportive of their interests, were not so coherent in their presentations at the time. They had pretty much the same values of distribution of wealth as the “progressive liberals” but a different set of values of recognition, or esteem, of who was worthy and deserving of recognition. Nancy Fraser calls these the “regressive neoliberals”.

Sectoral emphases aside, on the big questions of political economy, reactionary neoliberalism did not substantially differ from its progressive-neoliberal rival. Granted, the two parties argued some about “taxes on the rich,” with the Democrats usually caving. But both blocs supported “free trade,” low corporate taxes, curtailed labor rights, the primacy of shareholder interest, winner-takes- all compensation, and financial deregulation. Both blocs elected leaders who sought “grand bargains” aimed at cutting entitlements.

But the “regressive neoliberals” appealed to a different voting bloc. Their primary make-up consisted of the financial sector, the military manufacturing and extractive energy industries. But they usually spoke not directly as the weapons and oil and coal industries, but as supporters of “small business and manufacturing”. That front was far more appealing to a wider constituency. And as for their “recognition values”, these appealed to

- Christian evangelicals,

- southern whites,

- rural and small-town Americans,

- and disaffected white working-class

Nancy Fraser does not see the above constituency as necessarily natural allies with “libertarians, Tea Partiers, the Chamber of Commerce, and the Koch brothers, plus a smattering of bankers, real-estate tycoons, energy moguls, venture capitalists, and hedge-fund speculators”, but seems to think that the fact that they are all “bundled together” is, by and large, an “uneasy” alliance for now. In other words, Fraser sees hope for shifting the affections of the above four groups (evangelicals, southern whites, disaffected working class and small town Americans) into a more positive populist movement. But that’s getting way ahead of ourselves at this point in the discussion.

“The Regressive Neoliberals”

(The racism is, of course, flatly denied by most. See Strategies of Denial of Racism.)

Consequences of neoliberal politics (from Reagan to …)

I was about to conclude that heading with “Obama”, but then remembered that Trump himself has done a complete about face since his election and fully implemented (or simply allowed it to continue with even fewer restrictions) the neoliberal program himself.

Here is Fraser’s summary of the consequences:

Decaying manufacturing centers, especially the so-called Rust Belt, were sacrificed. That region, along with newer industrial centers in the South, took a major hit thanks to a triad of Bill Clinton’s policies: NAFTA, the accession of China to the WTO (justified, in part, as promoting democracy), and the repeal of Glass-Steagall. Together, those policies and their successors ravaged communities that had relied on manufacturing. In the course of two decades of progressive neoliberal hegemony, neither of the two major blocs made any serious effort to support those communities. To the neoliberals, their economies were uncompetitive and should be subject to “market correction.” To the progressives, their cultures were stuck in the past, tied to obsolete, parochial values that would soon disappear in a new cosmopolitan dispensation. On neither ground—distribution or recognition—could progressive neoliberals find any reason to defend Rust Belt and southern manufacturing communities. (my emphasis)

Thus far we have set out the scenario that is to usher in Trump.

Continuing . . . .

Fraser, Nancy. 2017. “From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump—and Beyond.” American Affairs Journal 1 (4): 46–64. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2017/11/progressive-neoliberalism-trump-beyond/