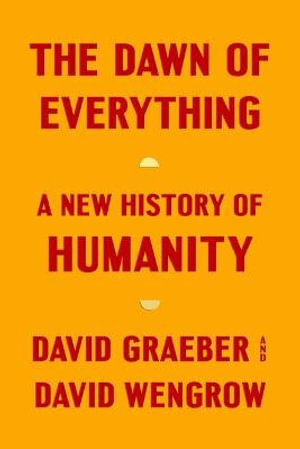

When reading about Herod the Great recently I was reminded at one point of my recent post about The Dawn of Everything. Herod prided himself on showering the poor with free food — following the “bread and circuses” custom of aspiring and established political leaders in Rome.

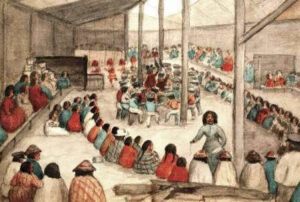

Northwest Coast societies, in contrast, became notorious among outside observers for the delight they took in displays of excess. They were best known to European ethnologists for the festivals called potlatch, usually held by aristocrats acceding to some new noble title (nobles would often accumulate many of these over the course of a lifetime). In these feasts they sought to display their grandeur and contempt for ordinary worldly possessions by performing magnificent feats of generosity, overwhelming their rivals with gallons of candlefish oil, berries and quantities of fatty and greasy fish. Such feasts were scenes of dramatic contests, sometimes culminating in the ostentatious destruction of heirloom copper shields and other treasures, just as in the early period of colonial contact, around the turn of the nineteenth century, they sometimes culminated in the sacrificial killing of slaves. Each treasure was unique; there was nothing that resembled money. Potlatch was an occasion for gluttony and indulgence, ‘grease feasts’ designed to leave the body shiny and fat. Nobles often compared themselves to mountains, with the gifts they bestowed rolling off them like boulders, to flatten and crush their rivals.

So far so good. The authors towards the end of the book describe the archaeological evidence of the first Mesopotamian city, Uruk, and the evidence for the temple complex there accommodating the poor:

It is often hard to determine exactly who these temple labourers were, or even what sort of people were being organized in this way, allotted meals and having their outputs inventoried – were they permanently attached to the temple, or just ordinary citizens fulfilling their annual corvée duty? – but the presence of children in the lists suggests at least some may have lived there. If so, then this was most likely because they had nowhere else to go. If later Sumerian temples are anything to go by, this workforce will have comprised a whole assortment of the urban needy: widows, orphans and others rendered vulnerable by debt, crime, conflict, poverty, disease or disability, who found in the temple a place of refuge and support.

One wonders, of course, about the possibility that these people were slaves. Graeber and Wengrow note,

There is a possibility some were already slaves or war captives at this time (Englund 2009), and as we’ll see, this becomes much more commonplace later; indeed, it is possible that what was originally a charitable organization gradually transformed as captives were added to the mix.

From here, we move on to the question of how authoritarian societies arose and to quote a portion of what I covered in an earlier post,

The shorter version of Steiner’s doctoral work . . . focuses on what he calls ‘pre-servile institutions’. Poignantly, given his own life story, it is a study of what happens in different cultural and historical situations to people who become unmoored: those expelled from their clans for some debt or fault; castaways, criminals, runaways. It can be read as a history of how refugees such as himself were first welcomed, treated as almost sacred beings, then gradually degraded and exploited, again much like the women working in the Sumerian temple factories. In essence, the story told by Steiner appears to be precisely about the collapse of what we would term the first basic freedom (to move away or relocate), and how this paved the way for the loss of the second (the freedom to disobey). . .

What happens, Steiner asked, when expectations that make freedom of movement possible – the norms of hospitality and asylum, civility and shelter – erode? Why does this so often appear to be a catalyst for situations where some people can exert arbitrary power over others? Steiner worked his way in careful detail through cases . . . Along the journey he suggested one possible answer to the question . . . : if stateless societies do regularly organize themselves in such a way that chiefs have no coercive power, then how did top-down forms of organization ever come into the world to begin with?

You’ll recall how both Lowie and Clastres were driven to the same conclusion: that they must have been the product of religious revelation. Steiner provided an alternative route. Perhaps, he suggested, it all goes back to charity. In Amazonian societies, not only orphans but also widows, the mad, disabled or deformed – if they had no one else to look after them – were allowed to take refuge in the chief’s residence, where they received a share of communal meals.

Bread and circuses, charity . . . and the rise of tyrants. The message to me is the importance of allowing everyone to participate in the distribution of their needs.

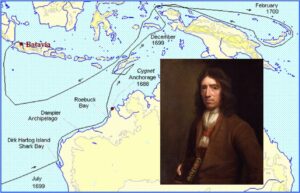

Graeber, David, and David Wengrow. The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021.