For readers interested in a few notes from The Pity of It All by historian Amos Elon.

For readers interested in a few notes from The Pity of It All by historian Amos Elon.

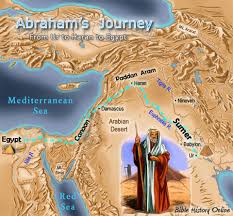

Herzl envisaged a modern Exodus organized on a “scientific” basis. He would go to the kaiser and say, “Let us depart! We are strangers here. We are not allowed to merge with the Germans, nor are we able to. Let my people go!” The kaiser would understand him; he was trained to understand great things. The Jews would depart, taking the German language with them; it would flourish in the new land, wherever that would be. Herzl was neither sentimental nor nostalgic when it came to the choice of a suitable territory: the homeland could be Argentina or elsewhere, preferably far from the imperial rivalries of the European powers. The place would be chosen by a committee of rational, scientific geographers and economists; the mass of Jews, however, would settle for whatever place they were offered. The new national home would not be “Jewish” but a multicultural, multilingual state like Switzerland, even though most citizens would probably con tinue to speak German. (285-86)

And the reaction to Herzl’s plan?

Bismarck never answered Herzl’s letter. Herzl was not surprised. . . . The reaction of most German and Austrian Jews to Herzl’s plan was hardly more forth coming. A Lovers of Zion movement of a few small, loosely organized proto-Zionist groups had existed, mostly in Russia and Romania, since the pogroms of 1882. In the West it counted no more than a dozen or so sympathizers in Cologne and a few romantically inclined Viennese Jews of Eastern European origin whose purpose was to help settle Russian and Romanian Jews as farmers in Palestine on a nonpolitical basis. . . . Nevertheless, in the fifteen years since its inception the project had attracted few candidates and was an economic failure. (286)

The reaction among Jews to Herzl’s plan ranged from ridicule to ignoring it to outright hostility.

Opposition to Herzl’s Zionism seemed more vehement in Germany than elsewhere in Europe. It was certainly more shrill. His program seemed to threaten German Jews to their very core, and German Zionists remained few and isolated for many years. Herzl tried in vain to interest Walther Rathenau in his cause. “The Jews are no longer a nation and will never become one,” Rathenau responded. German Jews were now a German tribe like Saxonians and Bavarians. “Zionist aspirations are atavistic.” (288)

The myth of an empty land waiting for a people without a land had not yet been born.

In Cohen’s opinion, the Jews’ task was “to go on living among the nations as the God-sent dew, to remain with them and be fruitful for them.” The Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums reproached the Zionists for assuming that the Arabs of Palestine would welcome an influx of Jews — one of the earliest warnings against the widespread assumption that Palestine had, in effect, no politically conscious native population; as a land with out people it was thought to be ideally suited for a people without a land. (289)

Up till 1909 nothing really changed.

With few exceptions, even those who were registered Zionists were “third-party Zionists,” that is, one Jew soliciting funds from a second so that a third might be able to settle in Palestine. German Zionists continued to be ardent German patriots. Their love of the fatherland was only “enhanced,” they proclaimed, by their love of the ancient Palestinian homeland: what they had lost there they had found again in Germany. The noted economist Franz Oppenheimer joined the Zionists despite the fact that his emotional and intellectual makeup, as he put it, was “ 99% Kant and Goethe and 1%Old Testament via Spinoza and Luther’s translation of the Bible.” In sum, few were touched personally by the cause, and even when they were, it was primarily as an activity “German Jews would lead and direct but in which the Jews of Eastern Europe must be the actors. (289-90)

From 1909 a new Jewish generation reacted differently to an evolving social situation in Germany but that’s another story.

Elon, Amos. 2002. The Pity of It All a Portrait of Jews in Germany 1743-1933. New York: Picador.