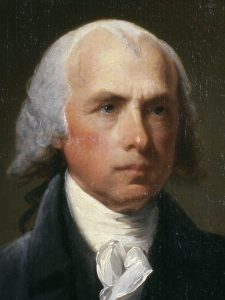

The first eight words in the alleged quotation below by James Madison, below, are false.

Here’s what Madison said about democracy:

Democracy is the most vile form of government . . . democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention: have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property: and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths. [The text in boldface is pure fiction.]

The Founders just didn’t trust the ordinary people and deliberately kept them at arm’s length, as can be seen from the way they drafted the Articles of Confederation and then the U.S. Constitution. (Arnheim 2018, p. 25)

Certain conservative authors insist these words from James Madison prove that the framers of the U.S. Constitution distrusted ordinary people and hated democracy. The above example comes from Michael Arnheim (Ph.D., ancient history) who is, according to the editors of the “for Dummies” series, “uniquely qualified to present an unbiased view of the U.S. Constitution.” (Arnheim 2018, back cover)

Uniquely qualified?

Dr. Arnheim provides no citation for the Madison quote, but you can find the true part in Federalist 10. Since so many versions and editions of the Federalist Papers exist, I’ll cite paragraph numbers rather than page numbers.

Before continuing, however, please be aware that the mischief does not begin and end with the fictional denigration of democracy. Conservatives will often, as Arnheim does, neglect to define the term, knowing that modern readers will conflate the common term “representative democracy” with Madison’s “pure democracy.”

We shouldn’t discuss terms like “constitution,” “republic,” and “democracy” as if they were simple English words. In the context of government, or in this specific case — a history of the U.S. Constitution — these are terms of art. We need to know how the authors at the time defined these terms in order to deal with them honestly. Fortunately, Madison et al. often gave perfectly concise definitions of the terms at hand. On the subject of democracy, he wrote:

From this view of the subject, it may be concluded that a pure democracy, by which I mean a society, consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert results from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party, or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is, that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives, as they have been violent in their deaths. (Federalist 10, para. 13, emphasis mine)

We can find several cases in the Federalist Papers in which the two main problems of “pure” democracies are discussed. In the first place, if the legislature is essentially the body of citizens (i.e., men of property, men of consequence) meeting together and voting publicly on all issues, then scaling it up to the size of a typical nation-state is impossible. Secondly, as Madison explains above, such governments are historically volatile and apt to make poor, even catastrophic, decisions.

“A republic — whatever that means”

Arnheim correctly states that Madison prefers the republican form of government over any other. But what exactly is a republic? Oddly, Arnheim looks to John Adams for a definition. Unfortunately, he can find only an unclear reference to the rule of law and how everyone in a republic is subject to this rule of law, not to a tyrannical monarch or an out-of-control parliament.

He notes that the Constitution itself guarantees that each state has a “Republican” form of government. But what does that mean, precisely? He writes:

There is no precise definition of Republican, but Adams’s views on the subject are a reflection of the Framers’ thinking (although Adams himself didn’t attend the Constitutional Convention, as he was serving as U.S. ambassador to Britain at the time). (Arnheim 2013, p. 28, emphasis mine)

You know who was at the convention? James Madison. I can’t understand why the so-called “Father of the Constitution” never took the time to explain the term.

Oh, wait. Of course he did.

A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure, and the efficacy which it must derive from the union. (Federalist 10, para. 14, emphasis mine)

In other parts of the Federalist Papers, the writers admit that the term republic has been applied to a broad swath of governments, some of which might better have been described as aristocracies with modest republican elements. But for the framers, their republic would be a government with representatives selected, via whatever means, by the people.

In fact, several of the founders did not shy away from the word democracy when describing the form prescribed by the Constitution. Arnheim seems to think that would be impossible. As noted above, he tells us Madison called it “vile.” I don’t believe Arnheim created this lie (most likely invented by Pat Buchanan in 2010), but he was quite comfortable with spreading it without checking the reference. The editors at Wiley also failed to catch the false quotation through two editions.

Arnheim writes:

The words democracy and democratic don’t figure anywhere in the text of the Constitution. In its original form, the Constitution was not democratic, and the House of Representatives was the only directly elected part of the federal government. The Constitution became democratic as a result of the rise of President Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party in the 1830s. (Arnheim 2018, p. 11)

The Founders didn’t trust the ordinary people. Democracy was a dirty word as far as they were concerned. (Arnheim 2018, p. 36, emphasis his)

Dirty words, done dirt cheap

His contention that democracy was a dirty word is at odds with the writings of Alexander Hamilton who, in a letter to Gouverneur Morris, acknowledged the shortcomings of direct democracy.

But a representative democracy, where the right of election is well secured and regulated & the exercise of the legislative, executive and judiciary authorities, is vested in select persons, chosen really and not nominally by the people, will in my opinion be most likely to be happy, regular and durable. (Hamilton 1777, italics his, bold emphasis mine)

James Wilson of Pennsylvania, a founding father who signed both the Declaration and the Constitution, used the terms democracy and republic interchangeably. To him, they meant essentially the same thing.

There are three simple species of government — [1] monarchy, where the supreme power is in a single person — [2] aristocracy, where the supreme power is in a select assembly, the members of which either fill up, by election, the vacancies in their own body, or succeed to their places in it by inheritance, property, or in respect of some personal right or qualification — [3] a republic or democracy, where the people at large retain the supreme power, and act either collectively or by representation. (Wilson 1896, p. 544, emphasis mine)

Did Wilson think democracy was a dirty word? Did he distrust ordinary people?

What is the nature and kind of that government, which has been proposed for the United States, by the late [constitutional] convention? In its principle, it is purely democratical: but that principle is applied in different forms, in order to obtain the advantages, and exclude the inconveniences of the simple modes of government.

If we take an extended and accurate view of it, we shall find the streams of power running in different directions, in different dimensions, and at different heights, watering, adorning, and fertilizing the fields and meadows, through which their courses are led; but if we trace them, we shall discover, that they all originally flow from one abundant fountain. In this constitution, all authority is derived from THE PEOPLE. (Wilson 1896, p. 35, emphasis mine)

Arnheim has shown himself to be uniquely qualified to present the modern conservative views of government, which are unabashedly antidemocratic, while studiously ignoring the actual texts written by the framers. In fact, he’s so often wrong, that I intend to use him as a kind of failed anti-text for the next couple of posts.

Arnheim, Michael T. W. 2018. U.S. Constitution for Dummies. Second edition. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Hamilton, Alexander. Letter to Gouverneur Morris, 19 May 1777. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0162

Madison, James. Federalist 10. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-10-02-0178

Wilson, James; James DeWitt Andrews, ed. 1896. The Works of James Wilson, Vol. I. Chicago, Illinois: Callaghan and Company.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

The essential component to our democratic/republican form of government is the limitation of governmental power. Those powers are clearly enumerated. The government can do X, Y, and Z, but may not encroach on individual rights beyond those stated powers.

Clearly, legislation and executive interpretation have gone well beyond the constitutional enumerated powers throughout our history, but that phenomenon has accelerated from the early 20th century onward. Now, the courts have essentially appropriated the powers of both the congress and the executive branches, further eroding individual liberty and the general welfare of the nation.

I think the essential component is the distribution of power. In federalism, powers are distributed between the states and the national government. Within the national government, the three branches control the separate “departments” (in the founders’ lingo) while keeping a check on the others. (And yes, the Constitution places strict limits on that national government.)

Right now, the legislative branch has rolled over and completely relinquished its authority as a contending power. It refuses to provide oversight. The courts may or may not be up for the task. I suspect they are not. The states may try to fight back, but the tasks ahead are enormous. The erosion feels unstoppable.

We are living in “interesting times.” I’m watching the brutal, unnecessary, unforced dissolution of a republic that I once served. What was once unimaginable now seems inevitable.

The “Founders” used the term “Levelers” to describe Democracy. They were Classicists. They believed that only those of the “right class (or was it “caste”?) had right to govern others.

It may be helpful to read Michael Parenti’s “Democracy For The Few”. You can probably find a PDF copy if you Google it online.

The big problem with democracy (in the broad sense of the word) if you’re a large property owner is that you’ll likely be outnumbered by non-property-owners. This then increases the probability that a democratic government will vote your property away from you.

(and this is *not* something they would have said out loud, or rather, if you’re expecting a new constitution to be adopted by plebiscite and the non-property-owners will be the vast majority of the voters, then you want to stay away from arguments unlikely to resonate with non-property-owners. Better to go on about the ever-expanding sequence of clusterfucks the Athenians got themselves into (cf. Thucydides) from democratic assemblies voting for Stupid Things…)

And it’s important to remember the context of the 1787 convention: Shay’s rebellion had just been suppressed, but it scared the absolute living shit out of the founders (Jefferson was one of the few who was all, “relax, this sort of thing is to be expected and we can trust The People to eventually do the right thing,” [I suppose I should probably look up the actual quote but I’m lazy]; problem being that he was off in France being the confederation ambassador getting all excited about what was happening with Louis XVI, and this particular input was not wanted anyway; never mind this was all before the French Revolution went sideways…). The priority was on establishing a stronger central government meaning a stronger national rule-of-law to better protect property rights.

The other important piece of context is that the first volume of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire came out in 1776 with subsequent volumes following in rapid succession like Harry Potter novels. There may have been a bit of delay getting it across the Atlantic but, make no mistake, it was on everybody’s reading list. Which meant nobody needed to go into detail on what a “republic” was; everybody had Rome on the brain.

… though I also think the case can be made that the founders were NOT trying to emulate the Roman Republic so much as the Roman Principate — specifically the initial part of Augustus’ reign where he was still being very careful in his Senate dealings and the framing of his own position so that he wouldn’t get knifed in the back the way his uncle Julius did…

which is why we have an Executive branch headed by a mini-emperor-like President rather than a pair of Consuls (also missing are the centuriate and plebian assemblies, tribunes, censors + associated machinery), and the question they spent the most time on was how you can keep enough power in the hands of the Senate and the People so as NOT to get stuck with a hereditary monarchy in which Tiberius/Caligula/etc can do whatever the fuck they want with no recourse. (You also have the history of the 2nd century AD where for a while it looked like Rome *was* finally starting to get out of the hereditary monarchy loop, and this persistant idea that if only Marcus Aurelius hadn’t screwed the pooch [in insisting that his {less capable} son succeed him] things might have turned out better.)

elections are obviously a piece of the puzzle, but they had no problem putting in arbitrary bullshit and messing with the formula to get the results they wanted — hence the electoral college, the 3/5 rule (so that the South could control the House while the North controlled the Senate), the structure and primacy of a Senate (chosen by state legislatures, not directly elected) on various matters (I think they really *did* want a House of Lords but establishing a new aristocracy was just NOT going to fly)…

…in short, I don’t think there’s any doubt that the founders (mostly) didn’t want majority rule. Where modern conservatives go off the rails is in thinking this is a feature rather than a bug.

OP: “…the modern conservative views of government, which are unabashedly antidemocratic, while studiously ignoring the actual texts written by the framers.”

And not correctly framing the pre-war, pre-constitutional competing liberal power structures.

See the first twenty minutes @ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FCShsGCkOP4

“The REAL Cause of the Revolutionary War”. YouTube. @AtunSheiFilms. 15 March 2025.

“QUOTE”

[19:18]

I see the 12 years of unrest and Discord from 1763 to 1775 as a growing rift between two competing liberal power structures. I think there was more variation of liberal government within the colonies themselves than between say New York and London but what set British liberalism apart was that it did double duty both as a government by capitalists for capitalists and as a seat of Imperial Power. The British government had additional responsibilities that the governments of the 13 colonies simply did not among them the defense and maintenance of a vast Global Empire up until the 7 Years War British and American power structures had been symbiotic mutually beneficial and broadly ideologically indistinguishable but following the French defeat their material interests no longer aligned.

Bankrupted by the war, Parliament asserted their economic and political superiority over the colonies instituting mercantilism abroad while enjoying the fruits of capitalism at home.

1. They began to enforce “Customs Regulations” which they had previously turned a blind eye to.

2. They outlawed Colonial paper money.

3. They ordered Colonial legislatures to provide funding for the regular military.

4. And of course, they levied horrifically un-popular taxes . . . during an economic downturn [that] hit the working class especially hard.

But the colonists first impulse was not to overthrow the government and declare independence. In the 1760s the goal was simply to coerce Parliament into repealing the new impositions.

Wealthy Coastal Merchants (for whom armed insurrection against the crown was as yet unthinkable), started boycotting British goods and sending formal petitions to London.

And while the merchants exerted polite but firm pressure on British economic interests, radical populist groups emerged from the ranks of lower middle and working class colonists, smugglers, mechanics, artisans and farmers who were angry about their increasingly desperate economic circumstances.

[21:34]

“/QUOTE”