This post is a sequel to Not Finding the First Jesus, Look for the Last. What follows assumes one has read that post.

It is the orthodox view that Jesus came in order to fulfil the Jewish Scriptures, but he did so in a manner that defied the expectation that the messiah would conquer the enemies of the Judeans. I have suggested that this view of Jesus arose in a wider context of ideas whereby a Jesus or Saviour figure came to overthrow the works of the Old Testament creator and lawgiver god.

My view is built on Nina Livesey’s argument for Paul’s letters being produced by one of the several “Christian schools” that existed in Rome in the second century. As I pointed out in my previous post, I have found it difficult to understand how the kinds of teachings we associate with “gnosticism” — arguing that Jesus did not have a flesh and blood body, that the Jewish god was evil, that creation itself was evil — arose from what we know of our gospels and letters of Paul. But as per my previous post, I think that the relationship between those “gnostic” ideas and the ideas of orthodox Christianity makes sense if we set orthodoxy as the latecomer.

As Livesey points out, Paul’s letters, arguably critical of “Judaism”, arose at a time when Jews or Judeans were seen as having caused horrific losses to Roman military power in the Bar Kochba war of 132-135 CE and were themselves being severely punished. I would extend the time when Jews (and Jewishness) were widely abhored to the decades before when under the emperor Trajan there were widespread Judean revolts and massacres throughout the eastern part of the empire. (One might compare the widespread loathing of the “troublous” Palestinians – and Muslims – in Israel and the West today.) This was also the time when we see the emergence of “gnostic” or similar types of teachings arguing that the Jewish Scriptures testified to an ignorant (or even evil) god whose rule only promised death.

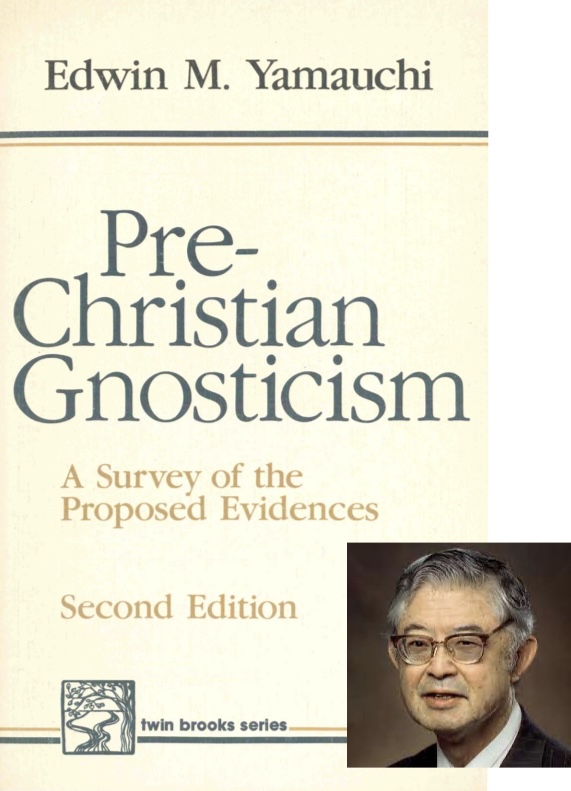

But there is an argument that “gnosticism” emerged after Christianity. This argument denies that there was any kind of Jewish gnosticism before the gospels and letters of Paul. Edwin Yamauchi pointed out…

But there is an argument that “gnosticism” emerged after Christianity. This argument denies that there was any kind of Jewish gnosticism before the gospels and letters of Paul. Edwin Yamauchi pointed out…

A major difficulty in accepting a Jewish origin for Gnosticism is to account for the anti-Jewish use which most Gnostics seem to have made of these elements. The anticosmic attitude of the Gnostics contradicts the Jewish belief that God created the world and declared it good. . . .

Many scholars therefore believe that it was probably through the mediation of Christianity that these Jewish elements came to be used in such an antithetical way. (Yamauchi, Pre-Christian Gnosticism: A Survey of the Evidences, 2nd ed, p. 242f)

Then a few pages later,

Gnosticism with a fully articulated theology, cosmology, anthropology, and soteriology cannot be discerned clearly until the post-Christian era. According to Wilson, were we to adopt the programmatic definition of Jonas ‘then we must probably wait for the second century’. Hengel would concur: ‘Gnosticism is first visible as a spiritual movement at the end of the first century AD at the earliest and only develops fully in the second century.’ (p. 245)

Both of these objections fall by the wayside if we place the whole game in the second century. Anti-Jewish ideas are readily understandable in a world that saw Jews as hostile to humanity “and the gods” and deserving of the bloodshed they were suffering. That is, in the times of Trajan (110s) and Hadrian (130s).

The second objection cited above expresses the point I am making: that yes, we are looking at second century developments.

It is not altogether coincidental that scholars who assume a Gnostic background for New Testament documents in some cases also adopt very late dates for these books, because late dates for these documents would make a stronger case for affinities with Gnosticism. Thus Rudolph dates Colossians to AD 80, Ephesians to the end of the first century, and both the Pastoral and the Johannine Epistles to the beginning of the second century. Koester dates the Pastorals to as late as between AD 120 and AD 160. (pp. 192f)

And why does Koester date the Pastorals to the middle of the second century? In large part because it is believed that it would have taken decades for Paul’s first century church assemblies to have evolved into the authoritarian episcopal structures that those letters indicate. But as Livesey has pointed out in her recent book, the “home gathering” situations of the letters is a rhetorical device aimed at building a sense of community among readers. They are not documenting a historical situation.

There is no independent evidence that dates any of our New Testament writings earlier than the middle of the second century. Yamauchi acknowledges that a second century date for the gospels and letters would make the possibility of a “pre-Christian” gnosticism more likely. I think the argument goes beyond mere chronological ordering of sources, though. That returns me to the point I was making in my previous post.

In coming posts I may (as much for my own benefit as anyone else’s) post notes on various teachers who appear to me to have preceded (proto-)orthodox Christianity and whose followers appear to have engaged with the new gospels and Pauline writings.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

If the NT writings cannot definitively be dated before the 2d C, that still leaves open the question of what form Christianity took in the 1st C, or, I suppose, whether it had much form at all. As far as I can tell, the claims of Neronic persecution of Christians (blaming them for the fire, etc.) can neither be proven nor disproven. We have, as I mentioned in a previous comment, the Book of Revelation; and I don’t know what evidence exists for dating of that document, but its Jesus Christ is an avenging Messianic figure unrelated to the gospel Jesus or the crucified Pauline one. If this predates the Gnostics, then there was a pre-Gnostic Christianity, but I don’t know how “orthodox” it would be considered.

If we align with Witulski’s Hadrianic date for Revelation, we have a Jewish Christianity that denounces “wayward Christians” in the 130s. The account of Nero’s persecution is surely suspect for the reasons Doherty et al have listed.

I can see nothing that obliges us to date any form of Christianity earlier than the second century.

Well, you have an existing Jewish Christianity that is addressing itself to 7 existing Christian churches, the members of which have had time to stray. ?

Yes, if we are looking at the 130s for Revelation, then looking back on erstwhile associates from the 110s allows ample “time to stray”.

I think that the Letter to the Hebrews has the strongest likelihood of being a 1st century CE Christian text, if any Christian texts were from that time. This is because even as it strains to argue that Jesus as hevenly high priest and sacrifice is superior to any Earthly Temple, it treats the Temple in Jerusalem as still standing, without even any forshadowing that the temple would be destroyed.

Labels inevitably conceal uniqueness. There were any number of disenfranchised Jewish sects in late 2nd Temple ‘Judaism’. Standard objections to a natural Christain origin are based upon a ridged institutional from of Judaism and dismiss the widely diverse species of Jewish worship. Qumran elevated an exiled priest to be the inspired reinterpretor of the sacred texts, they certainly included extensive typologically derived symbolism, known only to insiders. It’s even possible they thought of him in terms of divinity. The Alexandrian school certainly embraced the concept of concealed divinity at work on earth. It really is a small leap from the concept of the Logos/power of God embodied in Melchizedek, Aaron or Enoch, to the same being embodied in Simon or a figure with the mystical/honorific name ‘Jesus’. The belief in disguised emanations of the ‘One’ is found centuries BCE. Did they fit a label “Gnostic”, IMO yes. My definition of Gnostic, if we need one, is the belief that the secrets of the divine were not to be found in the Temple cult (at Jerusalem or Abydos) but rather through revelation, syncretism and eisegesis.

AS I see it, the concept or idea of “Gnosis” goes back to the early Pre-Socratic Greek philosophers. “The One” was personified as “Logos” and “Sofia” but it’s just different names for similar ideas.

I’m sure I’ve made this comment previously somewhere on Vridar, but it bears repeating: Irenaeus knows and gives the names and places of the Simonians Menander, Basilides and Satornilus, and he claims that their teaching was a corruption of an earlier true Christianity, yet he is strangely silent about any opponents they faced from his own camp. No names and places of any from his own side who undertook to refute the three of them. And Justin too knows and mentions all three of those Simonians as belonging to an earlier generation but doesn’t mention a single Christian apologist who stood up to them. For the roughly 100-year period from the time of the alleged apostles till the time of Justin was there no anti-Simonian figure worth mentioning? It is as if Justin was the first. To my mind this silence and absence makes the best sense if in fact it was only around the time of Justin that proto-orthodoxy started.

Note that I no longer attribute the origin of Christianity to the Simonians. They were not Christians. They were people who believed in a Simon who wore, so to speak, many masks, only one of which was Jesus. Moreover, they did not claim to be Christians. According to Irenaeus, Basilidians said they were “no longer Jews, but not yet Christians” (“Against Heresies”, 1,24,6). But one of the groups whose beliefs and texts they decided to mess with was made up of believers in a Jesus (whether historical or symbolic), and the result was a number of Simonian writings that the proto-orthodox were able to subsequently modify and use to create their new religion. Simonian writings and the Septuagint were, in my opinion, the two largest sources the proto-orthodox tapped.

So, in hindsight, a more accurate title for my Simonian series of posts would be: “Christianity’s Debt to the Simonians”.

I’m coming to a similar conclusion — that the names Irenaeus gives us of early “heretics” are difficult to classify as “Christian”. They may have Jesus in their teachings, but there are other early “Christian” texts that either don’t or only scarcely mention “Jesus” — I’m thinking of the Shepherd of Hermas and Ascension of Isaiah. (I may be overlooking others.) In Irenaeus’s accounts, Jesus is given a pivotal role among these heretics as a saviour, but one has to at least ask whether the attention given to this Jesus is more to do with later (post Marcionite?) interest in the name of Jesus.

I like your observation that Irenaeus can appeal to no opponents of these early “heretics” — except for Peter contra Simon.

It is interesting though that the proto-orthodoxy did date Simon to the earliest stages of ‘Christianity’. It would seem they didn’t have to. Somehow they felt compelled to. Is there some reason to believe Simon wasn’t historical?

Neil, your most recent article in Vridar got me thinking…and researching. I

had recalled reading Dylan M. Burns work: (“Apocalypse of the Alien God. Platonism and the Exile of Sethian Gnoticism.” Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press. 2014) and other similar work.

But then I thought of the work of Asko Parpola and his brother Simo on the contacts between Mesopotamia and India. I suspect Egypt and China were also involved because of their common interest in studying “the Heavens” and the gods and goddesses they believed appearing therein as stars, planets, and constellations. Before even the invention of Cuneiform, all four civilizations used pictographic writing or scripts to record and later share their knowledge of Astronomy and religious ideas and practices with others. Only some of this pictographic writing has been deciphered but enough has been learned of the interaction of all four of these civilizations in what is now considered PREHISTORIC TIMES which indicates we have a whole lot more to learn about the “origins” of “Gnosticism” and “religion”.

I think anthropology has much to offer in understanding “spiritual/religious” developments — as societies progress through different stages there seem to be common rituals. I’d love to be starting life over and focusing on this aspect of ancient religions.

So are you considering that all the action is now happening in Rome?

Are there possible schools in Antioch, Alexandria and Athens and would the distances allow these cities do develop their own unique flavours that would then become sensational new ideas when inevitable exchange occurred?

I’ve always imagined Alexandria is the hot bed of Christian diversity, the primordial soup of religion, but it is a sort of inference based on limited evidence. Antioch likewise seems to have special prominence because of Acts ‘were first called Christians in Antioch’. Yet, while the Book of Acts may be useless history, you have to wonder why a ‘proto-orthodox’ writer would make this statement.

Also, would you think what NL calls ‘schools’ is the same as what Doherty calls ‘mystery cults’?

No, not only at Rome but evidence does point to Rome being a major centre to which would-be philosophers migrated. Jared Secord points out that anyone hoping to be recognized as “an intellectual” wanted to boast of having come from some prominent city capable of producing philosophers of some renown. So Antioch, Alexandria etc were all places of honourable heritage.

As for “mystery cults”, some philosophical schools seem to have imposed secrecy on their inner members (a tradition carried over from early Pythagoreans?) so I suppose they might be considered “mystery cults”. But many of the schools were also open about their teachings, sharing their publications and ideas for debate and (competitive) engagement.

This book may be of interest: “No longer Jews – The Search for Gnostic Origins”, by Carl B. Smith. The title, of course, is from what Irenaeus relays regarding the supposed Basilidean claim to be “no longer Jews, but not yet Christians.” But notice the “no longer” which implies they once were either born Jews or Jewish converts (proselytes).

Amazon gives this description of Smith’s book:

“After an extensive survey of the issues, Smith provides his own conclusions: first, that an early second-century dating for Gnosticism is most consistent with the historical details of the period; and second, that Egypt following the Jewish Revolt under Trajan (115-117 CE) provides a ripe context for Gnosticism’s most unique and definitive innovation, the rejection of the cosmos and the Creator God of the Jews. He argues that individuals closely connected with Judaism whether Jews, Jewish Christians, or gentile God-fearers may have responded to the rebellion by rejecting the God and religion that inspired this apocalyptic and messianic ferment. “No longer Jews,” they were now free to follow a higher God and way of life.”

Smith’s book was written in 2004, and so 30 years after Yamauchi’s. Yamauchi provided this blurb for it:

“The date of the origin of Gnosticism is still much disputed, even after the publication of the Nag Hammadi texts. There is, however, a general recognition by scholars of the significant Jewish elements in Gnosticism, though often used polemically, and a consensus that Gnosticism probably emerged in Egypt. Carl Smith presents a persuasive case for identifying the historical context which may have induced disillusioned Jews to contribute to the origins of Gnosticism in the revolt of the Jews in Cyrene and Egypt under Trajan. Even those who may not agree with Smith’s conclusions will appreciate the lucid manner in which he has expounded the issues and the evidences for emergent Gnosticism.”

Thus, “disillusioned Jews”.

Thanks, Roger. The book is happily available on archive.org: https://archive.org/details/nolongerjewssear0000smit

I would like to post a few observations of Smith since he engages with Pétrement and a Yamauchi and co bringing out additional insights.

His idea of “gnosticism” is specifically the opposition between the unknown highest god and the god of the Jews, and the related negative view of creation. Interestingly, he refers to Skarsaune’s note that the “incarnation” was a nonsense idea for both Jews and pagans, and that the Jewish idea that made sense was “adoptionism”, while the pagan idea was “docetism” — and since both of these are found among “gnostics”, we have our evidence both Jews and gentiles (Platonists) or at least Jewish-Platonists at the beginning of gnosticism.

Here is a passage I had been saving up for a post but I’ll use it here for now:

pp 146-150