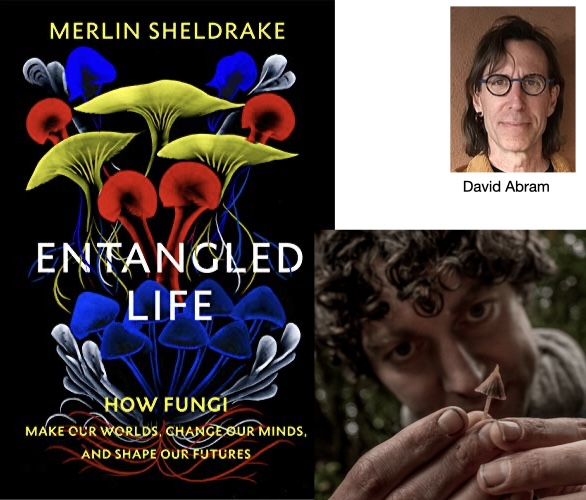

A friend of mine, the philosopher and magician David Abram, used to be the house magician at Alice’ s Restaurant in Massachusetts (made famous by the Arlo Guthrie song). Every night he passed around the tables; coins walked through his fingers, reappeared exactly where they shouldn’t, disappeared again, divided in two, vanished into nothing. One evening, two customers returned to the restaurant shortly after leaving and pulled David aside, looking troubled. When they left the restaurant, they said, the sky had appeared shockingly blue and the clouds large and vivid. Had he put something in their drinks? As the weeks went by, it continued to happen — customers returned to say the traffic had seemed louder than it was before, the streetlights brighter, the patterns on the sidewalk more fascinating, the rain more refreshing. The magic tricks were changing the way people experienced the world.

A friend of mine, the philosopher and magician David Abram, used to be the house magician at Alice’ s Restaurant in Massachusetts (made famous by the Arlo Guthrie song). Every night he passed around the tables; coins walked through his fingers, reappeared exactly where they shouldn’t, disappeared again, divided in two, vanished into nothing. One evening, two customers returned to the restaurant shortly after leaving and pulled David aside, looking troubled. When they left the restaurant, they said, the sky had appeared shockingly blue and the clouds large and vivid. Had he put something in their drinks? As the weeks went by, it continued to happen — customers returned to say the traffic had seemed louder than it was before, the streetlights brighter, the patterns on the sidewalk more fascinating, the rain more refreshing. The magic tricks were changing the way people experienced the world.

David explained to me why he thought this happened. Our perceptions work in large part by expectation. It takes less cognitive effort to make sense of the world using preconceived images updated with a small amount of new sensory information than to constantly form entirely new perceptions from scratch. It is our preconceptions that create the blind spots in which magicians do their work. By attrition, coin tricks loosen the grip of our expectations about the way hands and coins work. Eventually, they loosen the grip of our expectations on our perceptions more generally. On leaving the restaurant, the sky looked different because the diners saw the sky as it was there and then, rather than as they expected it to be. Tricked out of our expectations, we fall back on our senses. What’s astonishing is the gulf between what we expect to find and what we find when we actually look.

- Sheldrake, Merlin. Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures. Illustrated edition. New York: Random House, 2020. pp 15f