The second chapter of The Letters of Paul in their Roman Literary Context: Reassessing Apostolic Authorship (LP) by Nina Livesey (NL) challenges the general assumption among New Testament scholars that we have seven authentic letters of Paul, all written in the first century to real communities. If there is one yardstick for any historical reconstruction that I have repeated too many times to remember it is the necessity for independent confirmation of any claim we find in the sources. So it is with happy reassurance that I read NL beginning her discussion thus:

Scholarship that seeks to establish and provide facts about Paul, such as those found in Pauline biographies and chronologies, relies on the “authentic” letters themselves and thus lacks external verification. It also uncritically assumes that autobiographical statements of the inscribed letter sender (the Apostle Paul) are historically reliable. . . .

That Paul was active in the mid-first century CE is nearly undisputed within modern Pauline scholarship. Yet other than internal sources – the letters themselves and the book of Acts – evidence of Paul’s first-century activity is entirely lacking. . . . Scholarship on Pauline communities functions to reify these groups. Without credible evidence, it simply assumes their historicity, and appears to be merely filling a historical vacuum. (73 — bolded highlighting is mine in all quotations)

The letters speak of churches meeting in homes. NL suggests that these home settings rhetorically contrast with the hostile synagogue. Nor might it be merely accidental that we are given only the vaguest accounts of these communities: their exact locations and makeup are left to the readers’ imaginations.

NL attributes the strong interest in mining Paul’s letters for biographical information to the demise of the view that the Acts of the Apostles has much value as a historical source. But when we turn to studies of Greek and Latin letters outside biblical studies, we find little reassurance that the letters can yield much reliable information. NL draws upon classicist studies to inform us in depth in an appendix of the demanding education required to prepare a person to be able to write persuasively, and the gift of persuasion was very much what the curriculum was designed to achieve. Authors were taught the skill of presenting a type of character as an author and also the skill of creating imaginary audiences. With a knowledge of how literary education of the day trained pupils it becomes naive to assume that a face-value reading of an ancient letter necessarily reflects an exchange between a “true” author and recipient.

Pauline scholars have often written about the letters as if they are in effect a form of immediate and direct communication, open and honest as if the writer were in the presence of other persons and speaking directly to them. But again, that is an uninformed view. Letters like any other literary craft are never “natural”. The composer is always creating a type of persona that suits the purpose of the letter. More detail can be found online in one of the works NL references, Michael Trapp’s Greek and Latin Letters. See in particular pages 4-10, 27, 34, 37-44. (I have already mentioned another work that helps to inform NL’s discussion – Patricia Rosenmeyer’s Ancient Epistolary Fictions.)

The latter is central to ancient rhetorical theory, which grounds ancient epistolary theory. Ancient epistolary theorists recommended/advised authors to stylize their letters in such a way that their “presence” was made known and felt. As trained rhetoricians, these epistolary theorists likewise recognized a conceptual distance between an author and an author’s work, understanding that the former was always in full control of the latter. Letters are no different from other ancient written forms: they are authorial products that seek to persuade. Letters cannot on their own stand in for personal presence.

Moreover, only a constructed self is present in a letter, not a “real self”. (82)

In other words, we have no prima facie reason to assume that the Paul of the letters is any more genuine than the Paul in The Acts of Paul and Thecla or in the Acts of the Apostles.

NL indeed argues that our Paul of the epistles is a fictional character.

We have no external evidence of Paul; no noncanonical or non-extracanonical sources refer to him. While to argue against Pauline authorship based on a lack of outside evidence of Paul could be construed as an argumentum e silentio – and proving or disproving his existence is not possible – his absence from contemporaneous Hebraic, Greek, and Roman sources is nonetheless telling. (83)

Why “Paul”?

The Roman name “Paulus” is . . .

also largely unattested as a cognoman (a nickname) in the ancient world. As a nomen gentilicium (family name), it belongs to noble patrician families inside Italy. (83)

At this point NL footnotes two essays by Professor of Classics Christine Shea [CS]: a 2008 Westar conference paper, “Names in Acts 2: Our Little Roman, Paul”; a cameo essay in Smith and Tyson’s Acts and Christian Beginnings, “Names in Acts”. The former paper in turn cites H. Dessau’s 1910 paper that I have translated and made available here. Shea notes:

Alternate names and name-play are standout features of Acts, as they often are in Greek, Roman and Hebrew traditional tales:

- Stephen (=crown — the first martyr)

- Damaris (=wife)

- Felix (=happy)

- Porcius Festus (=pork)

- Theophilus (=god lover — the “ideal reader”)

- Jesus acquires the name Christ

- Simon is also Peter

- Mark is either Mark or John

- Joseph is called Barsabas and Justus

- Joses was renamed Barnabas

- Simeon was called Niger

- Barnabas becomes Zeus and Paul Hermes (Acts 14)

- Crispus is also called Sosthenes (Acts 18)

- the false prophet Bar-Jesus is also called Elymas when he opposed Paul/Saul

- Let’s not overlook the career of the persecutor Saul in Acts strongly echoes the Old Testament’s narrative of King Saul persecuting David – as was noted as early as the writings of Jerome and Augustine.

Name changes may be associated with a change in status such as transfer from an outgroup to an ingroup. Whatever the background, Acts certainly appears to consider names of symbolic importance.

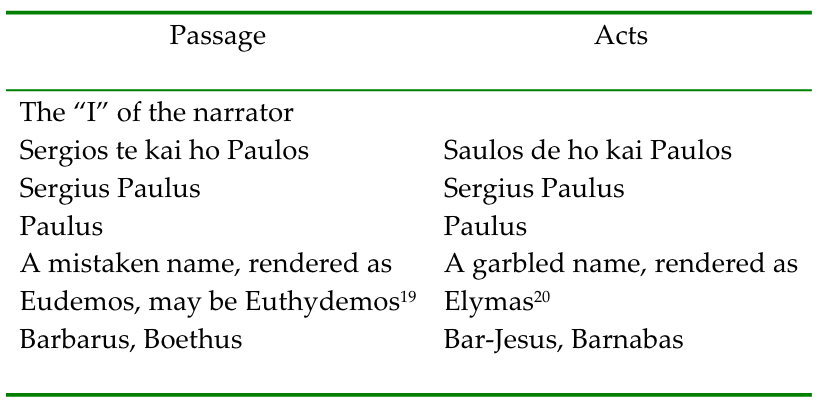

Around 162 CE the physician Galen (who was trained not only in medicine but also in philosophy more generally) came to Rome and wrote of some of his earlier experiences. In one of them he informs us of an episode with a prominent Roman (also schooled in Aristotelian philosophy) in Asia Minor, the city prefect Sergius Paulus, except that he introduces him as Sergios te kai ho Paulos [Σέργιός τε καὶ ὁ Παῦλος — easily mistaken as speaking of “Sergius and Paul” instead of “Sergius also named Paul”]. This Sergius Paulus was amazed at Galen’s fulfilled prophecy about a friend’s course of a disease and recovery and invited Galen to meet with him. Another who also wanted to speak with Galen was one named Barabus, an uncle of the emperor. Acts 13 speaks of Sergius Paulus seeking to meet one described as “Saul also called Paul” [Σαῦλος δέ, ὁ καὶ Παῦλος] as a result of impressive news about his activity in Cyprus. CS has drawn up a chart to show how well Galen’s “cast of characters lines up with Acts 13”:

My earlier post presents a detailed case for the name of the apostle Paul (changed from Saul) being in some way “borrowed” (as an honorific) from Sergius Paulus.

CS proposes the following possibility:

12 By the way, it is by no means certain that we can place a Sergius Paulus at the court of Sergius Paulus on Cyprus in Acts. There are several inscriptions which may or may not have bearing on the historicity of Paulus’ prefecture on Cyprus: (1) IGRR 3.935=SEG 20.302 is a fragmentary imperial decree on sacrifices which appears to mention a member of the imperial family of the 1st cent. CE. For many years commentators were content to restore the lines to name Claudius the emperor and to identify the Quintus Sergius named with the Sergius Paulus of Acts. Now, however, the emperor’s name has been restored as Gaius (Caligula), and the dating no longer works. (2) IGRR 3.930 appeared to name a Paulus as prefect, but now the position has been restored as dekaprotos, an office only known since the reign of Hadrian. Thus this proconsul Paulus served on Cyprus ca. 126 CE. . . . .

14 The fifth-century uncial ms Sinai Harris App. 5 (077 in Aland) contains just Acts 13.18-29. This seems to suggest that this episode circulated separately, apart from the Cyprus episode.

Now it seems to me that all these explanations [of commentators seeking to discern history in Acts 13] suffer from a hidden agenda: the desire to find every single word of the Pauline story in Acts historically accurate and consonant with what else is known about Paul from the letters, etc. However, although we can never inarguably place the Paul of history in the court of Sergius Paulus on Cyprus, we can certainly place the text which names Paul for the first time in close conjunction with the text that mentions Sergius Paulus.12 If we stepped back a bit from a pursuit of the historical Paul and were content to propose a solution that would deal with the history of the text, I think the explanation that in fact the text is about Sergius Paulus and “Paulus” in the text refers to Sergius would have more currency.

How would such an argument go? Let’s try this: there is a tale in common circulation about a Sergius Paulus. In this tale Sergius is called “Sergios te kai ho Paulos” apparently a common formula in Greek for indicating a Roman’s gens-name (nomen gentilicium) and cognomen. Someone, perhaps not too familiar with Greek or with Roman patricians, comes along and translates this formula as “Sergius and Paul” and thinks that there are two characters in the tale and that one of them is the letter writer. Bingo! The tale becomes associated with Paul.14 What kind of text might have generated this confusion?

The kind of text, CS suggests, is Galen’s:

Also Sergius Paulus [Sergios te kai ho Paulos], who not long after was appointed as a prefect over us, and Flavius, a consular already trained in Aristotelian philosophy, just as Paulus was, came to visit Eudemus. To them, Eudemus, recounting all that he had heard from me, said that he was grieved and affected by the prediction made regarding future developments and was observing how they would unfold.

When, around the same hour, those things also happened as had been previously predicted, Eudemus himself marveled and revealed my predictions to all those who visited him. These visitors were almost all individuals who excelled in both rank and learning in Rome.

When Boethus heard that I was highly skilled in anatomical investigation, he asked me to explain something about the voice and respiration—how they occur and through what instruments. After learning my name, he even told this to Paulus, who himself, upon becoming aware of me, asked me to explain something to him as well. He said that he was in need of an understanding of what is observed during dissections.

Similarly, Barbarus, the uncle of the emperor Lucius, who governed the region of Mesopotamia, also desired instruction from Paulus. Later, Severus, who was then holding the consulship and was also versed in Aristotelian philosophy, showed interest. (Translation from pp 611f http://archive.org/details/b29339339_0014.)

The Galen passage cannot be dated earlier than 162 CE, “but pieces of literary flotsam might attach themselves to the narrative any time until the texts are presumably frozen in the 4th century (at the earliest).” (CS 13)

Paul, before his conversion and as Saul, has long been associated with King Saul who persecuted David. More recent scholars have further discerned in that persecutor Saul allusions to King Pentheus who is the persecutor of the god Dionysus in Euripides’ play, Bacchae. Some have further identified the second part of Saul’s career, the time from his conversion, with the god Dionysus who turns the tables on Pentheus and is also well known as the conquering god. The author of Acts appears to have switched role models for his Saul-Paul character: first he is based on the persecutor of Dionysus and after his conversion he is modeled on Dionysus himself. The allusions such as these and many others come to focus on this episode in Acts 13. Though NL discusses a range of them, they are too many and detailed to include in this post.

The question that comes to my mind is this: If the author of Acts had a historical figure to draw upon then why would he or she have turned to the characters of myth and fiction as guides for how to create Paul?

Such is part of a wider ranging discussion by NL.

It seems likely that the new name “Paul” signifies the character’s first act of conversion of a prominent Roman official, whose name he then inherits. The adoption of a non-Jewish name likewise mirrors his mission to the gentiles (89 — with acknowledgement for this insight to NL’s student Caroline Perkins)

In the next post I will pick up NL’s analysis of how the various characters in Acts are echoed in the epistles.

Galen. Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia. Edited by Karl Gottlob Kühn. Vol. XIV. Lipsiae : C. Cnobloch, 1827. http://archive.org/details/b29339339_0014.

Livesey, Nina E. The Letters of Paul in Their Roman Literary Context: Reassessing Apostolic Authorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024.

Shea, Christine R. “Names in Acts.” In Acts and Christian Beginnings: The Acts Seminar Report, edited by Dennis Edwin Smith and Joseph B. Tyson, 22–24. Polebridge Press, 2013.

Shea, Christine R. “Names in Acts 2: Our Little Roman, Paul.” In Westar Fall 2008 Conference, 7–17. Santa Rosa, CA, 2008.