Continuing from:

- New Book Questioning Authenticity of Paul’s Letters

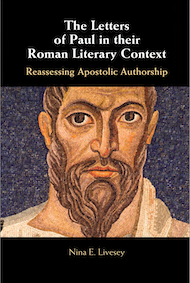

- Nina Livesey’s The Letters of Paul in their Roman Literary Context

This book argues that these seven letters* are … pseudonymous, literary, and fictional, letters-in-form-only. Their likely origin is Marcion’s mid-second-century speculative/philosophical school in Rome, the site and timeframe of our earliest evidence of a collection of ten Pauline epistles (c. 144 CE). Deploying the letter genre, trained authors of this school crafted teachings in the name of the Apostle Paul for peer elite audiences.

This study contributes to an important conceptual shift in our understanding of early Christianity. (2)

* – referring to the seven of the New Testament letters that are widely accepted as genuinely authored by Paul or his secretary: Romans, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, Philemon.

But how is the layperson, someone with an interest in Christianity but busy with other matters, to know “what’s what” about the sources? I am also mindful of the interest in the Christ Myth theory among several readers here and in the course of these posts I will point out where I believe some popular notions in that quarter might need rethinking.

Hopefully interested laypersons will find something to think about from this part review of The Letters of Paul in their Roman Literary Context.

A good place to start is getting our bearings on how we got to the position today where a core of the NT letters are considered to be genuine writings of Paul.

Scripture Status from the Beginning

To begin at the beginning, as NL does, we are not surprised to learn that notable Church Fathers such as Irenaeus and Tertullian (late second and early third centuries) appealed to their copies of Paul’s letters as if they were authoritative scripture. But is that how those (or the one) responsible for the letters meant them to be read? NL replies:

In that these authors are only at a slight remove, likely only several decades, from those responsible for the Pauline letters (see Chapter 4), it is reasonable to assume that their assessment of them as scriptural is how they were first envisioned to be. (36 – bolded highlighting is my own in all quotations)

Keep in mind that Irenaeus and Tertullian protested virulently against another prominent figure, Marcion, whom they accused of falsifying the letters. The actual words Paul supposedly wrote were matters of heaven or hell from the very first time we read about them in the external witnesses. That note does surely raise the question of how informal correspondence to scattered places could have been placed so soon on a par with Scriptures.

Criticism and Rescue

The European Enlightenment was the age of Isaac Newton, Mozart, Voltaire, Rousseau, Bentham, Locke and James Cook. The new rationalist spirit sought to discover what could be understood about Paul’s letters by examining what the letters indicated about the situation of the author and his addressees. It is worth noting some of the milestone critics for a better perspective on modern views:

Edward Evanson (1731-1805) proposed criteria and tests to determine the authenticity of the letters and their historical reliability.

His conclusion: All except for 1&2 Corinthians, 1&2 Thessalonians, Galatians and 1&2 Timothy were inauthentic. The only trustworthy gospel was that of Luke. Acts was also a useful guide to testing which letters were genuine.

As we too often find even among modern scholars, Evanson’s criteria and methods were often circular and more subjective than he might have liked to admit.

Wilhelm M.L. de Wette (1780-1849), assuming the letters to be genuine, laboured over reconstructing the historical setting of those to whom the letters were written along with teasing out clues that would allow a more graphic biography of Paul himself. This approach

serves to give the impression – without adequate evidence – of the realia of Paul, his communities, and the letters as genuine correspondence . . . . (41)

The reader is taken away from the main theological and doctrinal contents of the letters and ushered into a socio-historical-biographical world of Paul and his churches. The foundations of this world, however, are the letters themselves along with Acts, so again we encounter a circular process. The letters are understood in terms of the social world and persons and communities that are taken from the letters themselves.

De Wette had the imagination and gift to breathe life into Paul and his communities, their trials and successes, but alas, reading imaginatively into a text and seeing a life behind it is not the most disciplined of scholarship.

De Wette has won a more positive memory for his dissertation arguing that Deuteronomy was composed around the time of Josiah, not by Moses, in only a few dozen pages.

For at least one-hundred and thirty years, W.M.L.de Wette (1780-1849) has been cited in practically every scholarly discussion of the history of textual and source criticism of the Pentateuch . . . (Harvey/Halpern, 47)

You can peruse a translation of his Historico-Critical Introduction to the Canonical Books of the New Testament at archive.org.

Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792-1860)

F.C. Baur (not to be confused with Bruno Bauer) is a name many readers have heard of for good (or “not so good”, depending on your point of view) reason. His influence is still with biblical scholarship however much his views have been modified. Baur’s focus was on understanding Christian origins. He concluded that Christianity arose from a “spiritual insight” under the guiding light of Paul in reaction against an essentially legalistic Judaism led by the apostles James and Peter. For Baur, only four epistles were genuine: Galatians, 1&2 Corinthians, Romans (the Hauptbriefe). Those four were to be the platform from which to view Christian origins: Acts was unreliable as history.

Baur’s analysis, however, contained a fatal methodological flaw. He deployed circular reasoning. That is, “NT documents [the Hauptbriefe] are used to reconstruct early Christian history; the reconstruction of early Christian history provides the framework for the assessment of NT documents [the Hauptbriefe].” Otherwise put, Baur posits a great rift between Judaism and Christianity from reading the Hauptbriefe, and then relies on those same letters to confirm his historical reconstruction. (45f)

Further, NL points out that Baur came to his understanding of Christian origins largely as a result of his attachment to the notion that Judaism was a kind of primitive legalistic religion and Christianity a liberating spiritual one, along with the belief that ancient historical narratives almost by definition windows, however much darkened, into real historical events. There was also a prevailing view that history’s conflicts were stepping stones towards an overall advancement of human civilization.

Critics arose but in varying ways they embraced Baur’s assumptions — especially their high esteem for the person of Paul as a religious innovator. How to determine a letter’s authenticity? Four guidelines prevailed:

1. Did a letter fit the Christian-spiritual vs Judaism-legalistic model of Christian origins? This question led to the final conclusion, still accepted today, that seven of the letters are authentic: Romans, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, Philemon.

2. Did a letter conform to Pauline style?

3. Are there early external witnesses to a letter?

4. Did a letter agree with Acts?

Such guidelines have become standard to the extent that I think many lay readers accept them as reasonable grounds for assessing authenticity. NL prompts us to pause and think and take note that they cannot function as independent tests of authenticity.

Thus NL traces the emergence of criticism of Paul’s letters through to the current generally held opinion that seven are from the hand of Paul or his secretary. Paul is the pivotal genius responsible for the shape of Christianity.

The main point that NL is stressing is that the value of these letters since the Enlightenment rests on their historical veracity and what they reveal about the true historical situation of the early church.

I add a note here for those who rely on Paul’s letters for their view that Jesus began as a mythical figure who was later historicized. If we remove ourselves from Baur’s influence and consider the possibility that none of the letters are first century compositions and not written many years before the gospels, how securely can we maintain the interpretation that their author understood Christ to have been a heavenly and not an earthly figure? If he were writing around the same time as the gospels were appearing would we not expect some explicit evidence — whether in the gospels, letters or other sources — of a clash of the heavenly against the earthly career of Jesus? Might not the dearth of historical details of Jesus in the letters simply be a consequence of the author/s placing themselves as an independent voice in a post earthly Jesus time setting?

Genuine Letters?

In many ways Paul’s letters don’t look like other letters. Compare for a start the rambling openings in which the author asserts his authority and makes historical notes about the recipients on the one hand with the normal letter opening of the time on the other: “To Rufus, Greetings…” The foundational scholar on this question is the philologist Gustav Adolf Deissmann (1866-1937).

As with Baur, NL addresses the apologetic assumptions guiding the investigation. The letters look different, Deissmann explained, because they are written within a spontaneous spiritual fervour that cast aside formal literary discipline and wrote from the heart. (Another scholar attributed the “uniqueness” of the gospels to a similar origin.) The letters were “artless, personal, genuine, and [therefore] historically reliable” (57).

Deissmann and others scoured ancient personal letters especially from Egypt and the Levant for comparison, studying presentations and words used in known manuscripts and newly discovered papyri, to find “natural” settings for many of the details (biographical, structural, wording) thus “confirming” their genuineness.

For NL, the enormous scholarship undertaken in these studies was misdirected. For example, Paul’s letters are closer in length to the letter-treatises of upper class Romans like Cicero and Seneca than to any personal letters from the papyri.

So scholarship has ever since been seeking to find commonalities between Paul’s letters and other letter formats to establish that they are genuine letters, while at the same time putting their differences down to the unique situation of early Christian “spiritual life” and particular circumstances. We are asked to believe that the letters are genuine outpourings from the intoxication of “new beliefs”, especially the expectation of an apocalyptic return of Jesus. It is sometimes claimed that a letter of Paul is essentially a “directly spoken world” without literary artifice without any authorial attention to literary artifice. Such a view defies all that we otherwise know about any form of writing.

But biblical scholarship in some quarters at least has come to learn (especially, as I understand it, from anthropological studies) that new religions do not romantically erupt in a wave of spiritual fervour generated by new beliefs (such movements usually break out within established religions) but that rather, “in the beginning”, is ritual, practice. Myths come later to explain the rituals.

Deissmann posited an understanding of early Christianity that was ahistorical, and mythical. There was no Urchristentum as Deissmann (and Overbeck) imagined. Modern scholars of religion remark that rather than a concept or belief at a religion’s core, one finds instead practices. Only later is meaning applied to those practices. (64)

If beliefs and letters are not at the starting gate, what is?

The problem of positing “belief” as the seed and core of early Christianity is in part set out in an article available publicly (and cited by NL): The Concept of Religion and the Study of the Apostle Paul by Brent Nongbri. As further noted by NL, Nongbri draws upon “The Origins of Christianity Within, and Without, ‘Religion’: A Case Study”, which is the final essay in William Arnal’s and Russell McCutcheon’s The Sacred Is the Profane. The Political Nature of “Religion”. (The title is a reply to Mircea Eliade‘s pioneering The Sacred and the Profane of 1959.) Arnal and McCutcheon address the general isolation of biblical studies within the broader academy along with their all too often clearly flawed methodologies. “Religion” itself is largely a modern concept that has the unfortunate result of deflecting scholarly investigation away from specific practices, community behaviours and identities, that formed the real foundation of what became Christianity. Our focus on New Testament and related texts further blinkers us from other evidence that suggest quite different practices and tastes that can be discerned in archaeological remains and in what we know of other community formations. Indeed, it is suggested that the New Testament authors meant to impose a new textual understanding on the communities. The authors of these texts were literati who “viewed themselves as schools”. The texts constructed Jesus as an outsider figure who represented the communities themselves. They don’t mention Bruno Bauer but BB said as much more than a century and a half ago. In Arnal and McCutcheon’s words,

Speaking about Jesus as a particular type of social strategy was attractive for exactly the same reasons that, at the same time and among similar people, escapist novels, Stoic philosophy, and voluntary associations also flourished. (Sacred Is the Profane, 168)

I find it very easy to accept NL’s argument given what surely must have been many displaced persons looking for a clearer identity after the destruction of the Jewish way of life in Palestine and beyond as a result of the savage wars of Trajan and Hadrian to suppress Jewish uprisings. Not only Jews themselves but the gentile proselytes and “god-fearers” who had been attracted to “Judaism” would have been seeking a necessarily revised identity.

Continuing…..

Arnal, William, and Russell T. McCutcheon. The Sacred Is the Profane: The Political Nature Of “Religion.” New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Halpern, Baruch, Paul B. Harvey, and Wilhelm Martin Leberecht De Wette. “W.M.L. de Wette’s ‘Dissertatio Critica …’: Context and Translation,” January 1, 2004. https://www.academia.edu/1202115/de_Wette_diss_crit.

Livesey, Nina E. The Letters of Paul in Their Roman Literary Context: Reassessing Apostolic Authorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024.

Nongbri, Brent. “The Concept of Religion and the Study of the Apostle Paul.” Journal of the Jesus Movement in Its Jewish Setting: From the First to the Seventh Century 2 (2015): 1–26.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Paul’s letters in the 140’s? I would think theorizing them that far out would end up clashing with the dates of other documents. The gospels seem to be based on Paul’s letters, so I’m thinking dates that late would wind up contradicting other things of a known date. But I suppose it’s possible that the ways these documents were dated were dubious, maybe a big over haul in document dating needs to be done, but it would be important to make a case for such a radical overhaul of existing views. Not closed to the view, just wary that there’s a heavy burden of proof to be met.

“Might not the dearth of historical details of Jesus in the letters simply be a consequence of the author/s placing themselves as an independent voice in a post earthly Jesus time setting?”

Interesting hypothesis, could also solve mysteries like Paul saying earthly rulers are good, if this a fake written long after the fact when Christ’s death wasn’t freshly on anyone’s mind.

On the other hand, Paul saying things word for word the same as the gospel Jesus (without attribution) doesn’t quite make sense; if a faker were doing that to show how apostles took up delivering Jesus’ teachings, why didn’t Paul ever more explicitly let us know he was quoting Jesus?

On the contrary, I think it is the conventional view that lacks independent supports for the early dating of the letters — a heavy weight that and has been all too breezily accepted by the mainstream.

Even if the gospels postdate the letters that is not a problem given that our first secure independent evidence for the gospels is the second half of the second century. (Or if one must, though I would argue the point, usher in Justin as the earliest witness in the mid second century.)

Postdating doesn’t require decades between each document. A gospel could be written in response to a letter collection within the same year the letter collection is published.

NL, however, tends to side with those who see the letters and gospels in dialogue. They emerge together, and some form of the gospels preceding the letters.

Since the very first time I came across the fact/claim Marcion was the one responsible for gathering /finding(?) the initial collection Paul’s letters I have had my doubts about their authenticity, and whenever I come across another piece of information that chips away at the current mainstream view I always come back to the line from the film, Life of Brian – “They’re(He’s) making it up as they(he) goes along.”

Something tells me that, eventually it will all be revealed as fiction.

But if Marcion had invented the Pauline letters, why would he present as purified versions of corrupt earlier letters? Surely, if he had invented them, he would have claimed to be presenting secretly well-preserrved documents. Cf., e.g., the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham.

Gospels and Paul in dialogue? I am unsure of a good example or two of Paul responding to the gospels, it might be awfully hard to rule out the other way around.

I subscribe to the hypothesis that Paul’s letters and much more were outputs of Marcion’s workshops. What I still need to piece together is why would anyone forge letters from “Paul” if he weren’t a pre-existing authority. If Marcion’s group, however, was also responsible for gLuke (or proto-Luke) and the Book of Acts, those may have been the backstories giving flesh to the created character of Paul/Saul. It is good marketing to create a desire before fulfilling it.

So Marcion’s group issues some authoritative sounding forged letters and then follow up by filling the need of people for an answer to “Who is this chap, Paul?”

I have just finished an interesting book “Christ Before Jesus” in which they make what seems to me to be a strong case for most of the documents of the NT being after 144CE when Marcion first published his works. They also argue that a religion based upon a christ was already begun and the Jesus character inserted after the fact.

That was a question that I had a hard time answering, too. There is an alternative scenario, though. The name could have been constructed at the same time as the character — the same way Judas and the Twelve appear to have been constructed for literary-theological purposes. And/Or perhaps any name could have been chosen under which to write the letters — but the controversy that they generated, because of the party that they were coming from, led to opponents claiming to have the “TRUE Paul” with their versions of the letters — and the status, the reputation, of the figure grew as different parties used what had begun as a relatively “innocent” name in their war for domination.

I struggle with most reconstructions, they all seem to have problems.

If Marcion did publish a canon that contained Paul’s letters and a gospel, then that seems to be a core element to the issue.

But where does all this fit with other content? Hebrews, Revelations and Logos writers who do not even seem to know anything about Jesus?

Why does Justin Martyr seem to refer to ‘Memoirs of the apostles’? Why does he ignore Paul but consume ‘gospels’?

What about Papias and Hegesippus? If we are bringing everything into mid 2nd century, then these writings are only milliseconds from the Big Bang! In fact, you would have to be putting Papias before the Big Bang!

Why do rationalists ignore Papias? I don’t mean we should literally accept the apologists claim here, but we should not dismiss the evidence that there was a collection of early Christian myths that Papias collected?

What about the Yeshu stories that seem to bear some resemblance to the Jesus story? Who were these Nazarenes and why the attempt to re-interpret the term ‘Nazarene’?

What about Q? Did Matthew and Luke use this? Where does gThomas come into it?

What about Valentinus and Cerinthus and the so-called ‘gnostics’?

Then we have the obsession with ‘Pilate’, it seems to be a very defining distinction between ‘historical’ based concepts of Jesus and the vague heavenly descriptions.

These seem to be all loose ends, that need to be addressed. Most experts and armchair experts seem to focus on just one small part of the jigsaw and leave out the rest.

Revelation could well be a Bar Kochba era writing — pre-Pauline. Hebrews seems to me to fit with the kinds of epistles being written — typological — during the Trajan era.

Why does Justin Martyr seem to refer to ‘Memoirs of the apostles’? Why does he ignore Paul but consume ‘gospels’?

I am not convinced Justin knew the gospels. He writes a hodge podge of stuff that contradicts the gospels in many respects and otherwise assumes their narratives do not exist. Ideas and interpretations were certainly floating around, being explored, and some of his text seems to have been part of a wider discussion that did find its way into the gospels and Paul’s letters.

Decades, yes, but not milliseconds. 😉 But I don’t know when the “Big Bang” happened or even if it did begin with a Bang at all. Not likely, I suspect.

I don’t think the later testimonies about Papias are ignored.

All part of the debates at the time. I see a parallel with the newer hypotheses being proposed in relation to the Pentateuch. The various schools of thought were in debate and often responding to one another.

If there was a Q — but why not? GThomas is usually dated late pace Crossan.

Exactly. They fit right in. What was that world of thoughts from which “orthodoxy” eventually emerged. We tend to see it all through orthodox perspectives, but that means we are overlooking so much — especially non-literary data. We know that before “orthodoxy” became the monopoly institution there were very different Christianities in the second century. The cross, for starters, is not even on the horizon among some Christian evidence.

Not according to the Gospel of Peter. There Herod was the one who crucified Jesus. I’m not sure what you are thinking of when you speak of “obsession” with Pilate, though.

I have had my disagreements with Doherty and those disagreements have been carried over with Carrier. I think both have made a mistake of trying too hard to hang on to some core mainstream notions so as not to appear too “out there”. I think Detering and the Dutch Radicals have been closer to the mark all along.

“obsession with Pilate”

It may have come about much later, as I am thinking about the ‘Acts of Pilate’ and the fact that he gets a mention in the Niacene Crede. These are possibly later developments, but I wonder if this did start becoming an important aspect of Christian belief in the later 2nd century.

I imagine Pilate was picked out of obscurity as a historical book-mark to place Jesus in history, but his role seems to get amplified over time.

Given the Yeshu stories are set in a different time, it is one of the loose ends, the question of why this period of time was chosen.

One possibility I imagine is a solution I might tongue in cheek attribute to the Christian apologist Josh McDowell, who tries to argue that Jesus arrival at this time fulfills the prophecy of Daniel. I wonder if a second century Christian came up with the same calculation and concluded that this is the time period to look for a historical Jesus. (I cannot recall how contrived this calculation was)

Of course, with very little to use, they might have found a Nazarene legend and shoe-horned it into place.

I understand that Doherty and Carrier are limiting themselves to a time-line based on traditional assumptions that they themselves are pulling down. I will credit Doherty with a sense of awareness on this, while Carrier would prefer to dig in. I think it is understandable that they work from this direction. It is like Copernicus still working from the assumption that the Sun is the centre of the universe because it is not a hill worth dying on.

But given all the time and space now available from pulling down all the old assumptions, are you moving towards a more condensed starting point? Maybe not a ‘Big Bang’ but perhaps a ‘Cambrian explosion’ of Christian works.

As for the problem of the heavenly cult coming into disagreement with the historical cult. How big a problem is this? Should we expect conflict over this, because I am not sure. Consider that the ‘Luke’ writer presents a historical narrative to Theolophilus who is likely Theolophilus of Antioch (if we assume a 2nd century creation). Theolophilus is now not ignorant of the ‘historical’ narrative, but from all we have, he continues to write about the ‘logos’ and never about the historical Jesus. Luke’s work does not convince him! yet, it is the very copy that Theolophilus received and perhaps even commissioned that becomes the core of our later copies?

(Of course, I am taking great liberties above)

I prefer to see “Luke’s” Theophilus as one of the many names he concocts in Acts — it’s the name of the ‘god-loving’ reader. At least that interpretation is consistent with the author’s love of introducting punning names in the narratives. There’s no independent evidence to associate a historical person. I see our gospel narratives as evolving from but one of multiple schools of proto-Christians that were not made mainstream until very late second century at the earliest — more likely even later. Irenaeus was a latecomer, after all, who was looking back and criticizing the various schools that had been in existence before him.

In making their case for the 2d C. composition of at least 3 gospels, Britt & Wingo argue that Luke’s initial apostrophe is directed at a Theophilus who was (they say) bishop of Antioch from ca. 169-182 C.E., a pagan convert to Christianity who wrote Apology to Autolycus. I have no opinion on this claim, but just offer it.

Yes, that Theophilus is always in the back of my mind. Maybe we could ask a Bayesian to determine the likelihood he is THE Theophilus, but then we would still be left wondering. Is it relevant to the question that the author of Acts indicates he is a companion of Paul? If so, the bishop of Antioch must have known Acts was a fiction.

The other name that leaves me intrigued is the first gentile head of the Jerusalem church after the Bar Kochba war — his name is said to be Mark.

It has taken me until this year to realize that traditional dating of these books is based on a faulty premise, i.e., that dating is related to factual events. It’s not. It’s based on doctrinal agendas, just like the Council of Nicaea. Once you realize that the gospel story is fiction, the most obvious method of dating is to start with attestation of its existence, which begins in mid-2d C. with Justin. This source I mentioned clarifies a plausible theory for Luke (Evangelion plus additions by –as they claim–Irenaeus, who also pens Acts). But what is the theory for Proto-Mark? I’d really like to know. This source says some of it comes from Josephus, which means it can’t come before the 90’s. But how does Proto-Mark get into Marcion’s hands? Is it through Cerdo? Where does it start? Mark & Evangelion are supposedly more in line with doceticism. Matt. & John use the pseudonyms they use for apostolic authority, which becomes the desideratum in the mid-2d C. The revisions include the Davidic genealogy to avoid the Greek descent from the heavens type of thing. I would love some ideas about Proto-Mark.

Exactly so. Philip Davies established the same methodological point back in 1992 when addressing the Old Testament. (Not long before he died he was applying the same method

wrt the NT but if challenging the OT was tough enough, then how much more…..)

What was it that Justin knew? How authentic are his surviving claims about various gospel (canonical and noncanonical) snippets? Cassell’s in chapter 3 has left me in doubt that he knew our gospels: https://archive.org/details/supernaturalreli01cass

One of the hardest ideas for me to accept was the derivative character of Mark’s Gospel. The opening seems so right despite the challenging question: Why start a life of Jesus with John? — until one is reminded of the second century dispute over whether the OT was replaced by an antithesis or fulfilled with new meaning.

And is Mark’s gospel really opposed to the Twelve as Ted Weeden and Mary Ann Tolbert so peruasively argued? Are not the Twelve learning?

Should the name Simon as the leader of the apostles also takes on new significance in the wake of the Bar Kochba War even if some form of the character had not been invented that late?

One reason to place the crucifixion during the Prefecture of Pilate is because it puts it ~40 years before the destruction of the Temple. Jeremiah warned of the destruction of the Temple 39 years before the Babylonian destruction. Jesus’ protest at the Temple parallels Jeremiah and even quotes directly from it with the ‘hideout for thieves” line.

Mark doesn’t give an exact year for the crucifixion, but he could have intended it to be 39 years in parallel with Jeremiah.