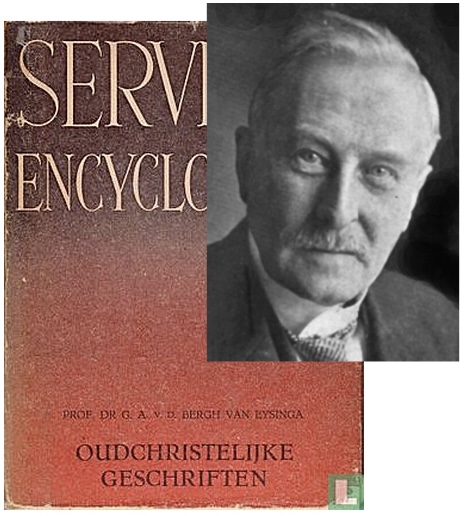

The following is by the “Dutch Radical” Gustaaf Adolf van den Bergh van Eysinga (1874-1957). I have translated it from the Dutch with the assistance of machine translators. The 1946 Dutch work from which this chapter (#4) on Galatians is an extract is available at https://archive.org/details/eysinga-servieres/mode/2up

The following is by the “Dutch Radical” Gustaaf Adolf van den Bergh van Eysinga (1874-1957). I have translated it from the Dutch with the assistance of machine translators. The 1946 Dutch work from which this chapter (#4) on Galatians is an extract is available at https://archive.org/details/eysinga-servieres/mode/2up

Bergh van Eysinga, G. A. van den. De Oudste Christelijke Geschriften. Servire’s Encyclopædie. Den Haag: Servire, 1946. pp 115-120

The bolding highlight is, as usual, my own.

115

Paul’s Letter to the Galatians

The well-known peculiarity of Paul’s letter is also found here, when Paul appears to be writing alone and with a staff of brothers (1: 2, 8 ff.). In order to reconcile the contents of this letter with the accounts of Paul’s travels in Acts, the Roman province of that name was assumed to be Galatia in the address, which encompassed much more than Galatia in the narrow sense, so that in this letter Paul would have been addressing congregations in Lystra, Derbe, etc. Schürer has rightly called this hypothesis a curious fallacy of criticism and sought the Galatians of the letter in Galatia proper, the central plateau of Asia Minor, the old Celtic country, the area of the river Halys. Nowhere does it appear that the inhabitants of Pisidia and Lycaonia were ever called Galatians. How could a letter with this address intend to exclude the actual Galatians? But then the great difficulty arises, that Paul, who is regarded as the founder of the Galatian churches (1: 6-9), has according to Acts never been to that mountain country. Furthermore, we are surprised by the assumption that they were susceptible to Pauline preaching and were considered to be very high as churches (3: 1-5), yes, even that they were able to understand this letter, which cannot be expected from an uncivilized mountain people. Loman therefore compared this letter to these readers with “Hegel for the Atchinese”. Supposing, however, that a short time ago they had been able to understand and agree with the profound Pauline Gospel, how can they now suddenly fall away and how can these spiritual Christians – not one, but all of them – become the prey of “someone” or “some” who are zealous for circumcision (l:6f; 3:1; 4:8-11; 6:12f)? How could they thus thwart Paul’s whole missionary work among them? As long as he was with them, everything went well (4:18), but as soon as he leaves, all those convinced Pauline Christians in all those Galatian congregations suddenly want to get circumcised.

116

Contrary to the tolerant spirit we know from elsewhere, where Paul becomes all things to all people to win them over for the Gospel (1 Cor. 9:19ff), this letter contains numerous vehement statements. Right from the start (1:8), there is a curse, and it is repeated (1:9); the designation: “foolish Galatians” (3:1,3); the words: “if you let yourselves be circumcised, Christ will be of no benefit to you” (5:2); “you who seek to be justified by the Law have severed yourselves from Christ; you have fallen from grace” (5:4). The sharpest statement is: “Oh, that those who are troubling you would even mutilate themselves (i.e., castrate themselves; Calvin found this too harsh and translated it as ‘perish’)” (5:12). However, everything said about this falling away is so vague that it could apply to many situations. When a specific circumstance is hinted at, the situation does not become any clearer: Paul had not intended to stay in Galatia, but illness forced him; “it was because of an illness (not: despite) that I preached to you” (4:13). Surely, it requires an extraordinary effort of body and mind to convert a foreign people, in an extensive land with many cities and without a specific center. Does this happen just incidentally and because of “illness”? People have speculated about the nature of this illness, thinking of epilepsy, malaria, leprosy; also an eye disease as a result of the stoning in Lystra (Acts 14:19). But illness or weakness is the traditional phenomenon that accompanies the gifts of the man of God, so that he does not boast in himself (cf. 2 Cor. 12:7ff).

If the writer wants to express the participation of the Galatians in Paul’s suffering, he falls into tremendous exaggeration: they received him as an angel of God, as Christ Jesus himself (4:14). How did these pagan-thinking and feeling people come to this not-so-obvious idea? Subsequently, it is said that they would have gouged out their eyes and given them to him, if that had been possible (only the word “necessary” would have made sense here), then it seems to be spoken to a small circle of intimate friends. However, one must not forget that Paul writes this to the congregations of Galatia! A clear proof of the artificiality of the whole. The conversion of Galatia is depicted as a miracle of God, and the Apostle as a superhuman being.

117

The historical part of the letter (1:6-2:21) contains a defence of Paul’s independence, but the whole is a fervent plea for the doctrine of justification by faith and not by works of the Law. Yet, something is always taken back from the sharpest statements. When Paul, 17 years after his conversion, goes to Jerusalem, it happens by higher guidance (2:2), but also out of fear of objections from some (2:1-10). He bitterly criticizes the Apostles there; he considers himself their superior and wants no fellowship (2:6), yet he presents his Gospel to them for judgment, and they force nothing upon him, indeed, they extend the hand of friendship to him (2:9). When Paul was converted by a revelation of Christ, he consulted none of those who were Christians before him (1:17). Allard Pierson drew attention to the improbability of this fact by the following parallel: a younger contemporary of Plato, born in Southern Italy, who as a fervent Sophist had rejoiced deeply over Socrates’ death, but comes to different thoughts a few years later, now realizes that thinking, feeling, teaching, living like Socrates, identifying completely with Socrates, is the one necessary thing. What does he do now? Quickly travel to Athens, where Plato and Alcibiades still live, who have seen, heard, and known Socrates? None of that. He travels to Egypt, stays there for three years, writes and speaks lifelong about Socrates and is considered by a gullible world to be the most credible witness about the wise man, the most reliable interpreter of his teachings and intentions!

The work of an earlier Pauline follower in the spirit of Marcion has been moderated in this letter by a more temperate, Catholicizing Paulinist. This dual origin is evident from the dual naming of the Rock Man, who is alternately called Cephas and Peter; and the capital of the Jews, which is referred to as Hierosalem and Hierosolyma. “Abraham’s seed” is used in one place (3:7, 29) as a title for believers, and elsewhere for Christ (3:16). There is only one Gospel, the Pauline one,—thus says the original, uncompromising author; there are two Gospels, for the more Jewish-tinged one is also recognized,—thus says the Catholic editor, who offers something for everyone (1:6). Alongside the sharp opposition to circumcision, there is indifference to this practice (5:6; 6:15). Although the Galatians are immediately instructed in the Pauline Gospel, they are expected to have a thorough knowledge of the Old Testament and especially the Law.

118