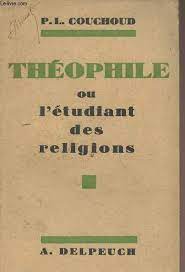

Here is one more passage from Couchoud’s Théophile. What I like about Couchoud’s expressed sentiments is his sympathy, his compassion for humanity, his tolerance (in a positive sense of that word) and understanding. The New Atheists like Richard Dawkins, Chris Hitchens, Sam Harris were angry, bitter, intolerant — and, I had to conclude, fundamentally ignorant about the nature of the religions they attacked and the reasons people believed in them. They created and attacked caricatures of both the faiths themselves and their adherents. At a certain level there was a truth behind those caricatures, and real harms have been committed by those religions, and I could to that extent laugh with their mockeries and feel some affinity with their disdain, but only at a superficial level. I was myself once deeply religious and had to admit that the religious believers in the world were, in fact, me. I was sincere, as far as I knew how to be sincere. I was, given my lights, as well intentioned as I knew how to be. I made horrendous mistakes, but in hindsight they were the result of ignorance, even if that ignorance was “ignorantly” self-induced, or from sheer weakness. If our own experiences are our primary guides to understanding “how others work”, I knew that there was something major lacking in the New Atheist attacks on religion. Couchoud, on the contrary, writes as a real humanist. If I was once a devout believer, I have no choice but to express the compassion and love Couchoud himself expresses for those who remain as constant reminders of ourselves.

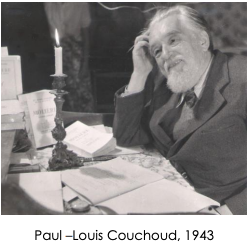

Paul-Louis Couchoud had the following essay published in 1928 — again from his Théophile (pp 216-219) — as introduced in the previous post. Again, it is a translation from the French.

REASONS NOT TO BELIEVE

In every era, apologists try to find new “reasons to believe.” But the reasons not to believe also multiply and gradually coordinate. It is useful to occasionally take stock of them.

Our culture is characterized by the growing importance of sciences that have humanity as their object. The naturalist-type scientist, whose object of study is nature, contrasts with the humanist-type scientist, well-versed in the methods of historical, philological, and psychological sciences. To both of them, Christianity does not appear in the same way.

The naturalist scientist, in a way, ignores it and is uninterested in it. They simply exclude from the scope of their science the simplistic and ill-founded solutions that the Bible seems to impose. After doing that, they are inclined to grant religion a special domain for which they feel, according to their education, respect or disdain.

The humanist scientist behaves differently. Religion is at the very center of their study. It has an inexhaustible interest for them. However, they do not grant it a special place among human phenomena. They examine it in its historical and psychological context. They do not seek to refute it, but they aim to describe its genesis. They bring it down from the absolute and place it in the conditioned.

In our times, the mindset of the humanist scientist tends to spread. Yet, more than that of the naturalist scientist, it is fundamentally incompatible with religious faith, especially with Catholicism. For anyone who undertakes free research of this kind and wants to maintain the integral faith defined by the Council of Trent, an internal crisis is either open or latent.

It will not take much effort, indeed, to discover the historical illusions and psychological illusions on which the majestic edifice of faith is built.

Let’s consider only three psychological illusions here.

Through this special state of meditation called prayer, can we change the course of things?

It is a very dear desire of humans. It was the driving force behind all magics and religions. It bravely defies experience. In fact, prayer is a beneficial and fruitful state, akin to inspiration. It has an impact on the person who practices it and sometimes on the world through them. But to believe that in the depths of inner silence, one touches a very powerful person, be it a saint or God, is nothing but a common illusion of duplication.

Do miracles occur in Lourdes or Lisieux that go beyond nature?

An eternal illusion, as old as humankind, to which one wholeheartedly lends oneself, as the taste for the marvelous is deeply ingrained in humans. Miracles around tombs belong to popular religion, older and more vigorous than Christianity itself. They only testify to an old human desire.

Is our self or, as they say, our soul, immortal?

This is the deepest and most industrious aspiration of humans. It has built the most beautiful mysteries and the most subtle philosophies. Does that mean it can change realities? Alas! Nothing in experience corresponds to this. Human wishes are of one order, and realities are of another.

Will it be said that these illusions are beautiful and comforting? That is a matter for discussion. In any case, a religion reduced to pleading for beauty and utility is sick. Christianity is condemned to be true or to perish slowly. For it cannot prevent men from standing up to it and saying: harsh, desolate, cruel, it is the truth we seek. And on it alone, we want to rebuild our moral life, build our society.

Against the revolutionaries who want to go all the way with free inquiry, today’s Christians are reduced to defending their traditions because they are ancient and beautiful. In this, they resemble the last pagans much more than the first Christians.

Do the others, the new men, harbor hatred or contempt for Christianity? Certainly not.

Christianity is of humanity. That is why it is precious to humans. It carries within itself an immense human heritage. It is by studying it in all its aspects, in all its depths, not to seek God but to seek humanity, that we will discover the future destiny of humanity.

The one who passionately examines Christianity not to seek God but to seek humanity is sometimes more full of broad sympathy toward it than the one who strives to believe but feels the burning restraint placed on their intellectual freedom and critical sense everywhere.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Re “The naturalist-type scientist, whose object of study is nature, contrasts with the humanist-type scientist, well-versed in the methods of historical, philological, and psychological sciences.”

Most people make the same mistake. Because history, politics, economics, etc. have adapted their descriptions to refer to themselves as “sciences,” people think they are. But they only did that to capture some of the shine from the natural sciences. When I was your there was a whole field of “Social Studies” but those got renamed as “Social Science” after a while. But are they.

The natural sciences have a final arbiter of what is and isn’t correct, nature. If you get something wrong, Mother Nature has been know to bitch-slap some sense into you. Scientist are often proven wrong (it is the way things work), and we find that out by querying nature.

Is there such a system for history or politics? (Hint: Nope.)

So, any distinction between “naturalist-type” and “humanist-type” sciences is specious at best, especially when it comes to religion. In our western religious traditions we have had thousands of years and the wealth of very wealthy churches to find the natural scientific explanations for church dogma and so far <cricket, cricket, cricket, . . .). This not due to some bias on the part of scientists, but rather there is nothing to be found.

I recall the story of the philosopher and the theologian. The two were engaged in disputation and the theologian used the old quip about a philosopher being like a blind man, in a dark room, looking for a black cat—which wasn’t there. “That may be,” said the philosopher; “but a theologian would have found it.” —Julian Huxley

Do you think there is a science that history and those in the humanities do use, like bayesian type analysis? Like what Carrier did in OHJ? I think so because, as Couchoud mentions in the latest exert you provided, they (we humanists in the liberal arts) examine the origins of religion. We can trace (especially faith-based) religion to our human nature and to our evolutionary impulses and developments. Maybe many don’t, like those in historical-Jesus studies, but many of us are scientists in the way we observe, hypothesize, test with corpuses and the tools of other disciplines, and then conclude about humanity with our examined results. What do you think about that?

Bayesian calculation is not an analysis. It is a simple formulation of a the probability of a particular outcome based upon known concrete data. It produces a concrete result. Estimating preconditions that seem reasonable has no part in what Bay’s formula is suitable for using.

fwiw, I compiled a list of posts addressing scholarly research into religion under the heading Religion – What Is It? Religion. I should update and expand it, though — for additional posts, see https://vridar.org/tag/belief-in-god/ and https://vridar.org/tag/religious-belief/

Nature can’t be fooled, but humans can.

The defiance of the four horsemen style is why they’re read, alas.

I don’t think morality without organized religion needs defense or advocacy. Religious freedom, though, always needs defenders.