I couldn’t resist. I had to add the evidence for the competition to the previous post. There with reference to Russell Gmirkin I set out the evidence for the biblical Garden of Eden being inspired by Greek literature. I know many would prefer I find something that adheres to a more conventional perspective, an account owes more to Mesopotamian traditions. So here are the closest scenarios from that part of the ancient world that I can find that might remind us of Genesis’s Garden of Eden. I will leave it to you to compare them with the Greek writings.

I couldn’t resist. I had to add the evidence for the competition to the previous post. There with reference to Russell Gmirkin I set out the evidence for the biblical Garden of Eden being inspired by Greek literature. I know many would prefer I find something that adheres to a more conventional perspective, an account owes more to Mesopotamian traditions. So here are the closest scenarios from that part of the ancient world that I can find that might remind us of Genesis’s Garden of Eden. I will leave it to you to compare them with the Greek writings.

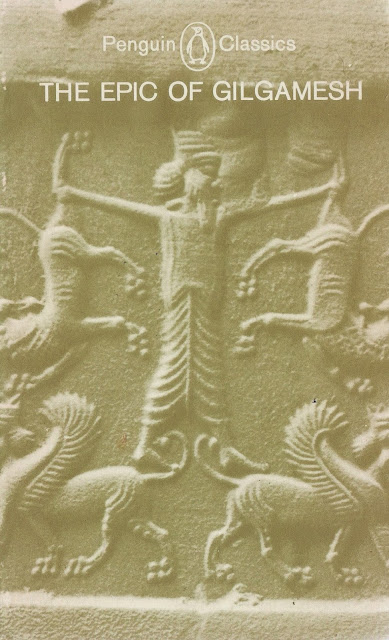

There was the garden of the gods; all round him stood bushes bearing gems. Seeing it he went down at once, for there was fruit of carnelian with the vine hanging from it, beautiful to look at; lapis lazuli leaves hung thick with fruit, sweet to see. For thorns and thistles there were haematite and rare stones, agate, and pearls from out of the sea. (Epic of Gilgamesh)

So Gilgamesh passes through a garden not for humans but for the gods on his way to see Utnapishtim, the Sumerian version of Noah.

There is a Sumerian description of “a land of immortality”, Dilmun:

In Dilmun the raven utters no cry,

The ittidu-bird utters not the cry of the ittidu-bird,

The lion kills not,

The wolf snatches not the lamb,

Unknown is the kiddevouring wild dog,

Unknown is the graindevouring . . ,

Unknown is the widow,

The bird on high . .s not his . . ,

The dove droops not the head,

The sickeyed says not “I am sickeyed,”

The sickheaded says not “I am sickheaded,”

Its (Dilmun’s) old woman says not “I am an old woman,”

Its old man says not ”I am an old man,”

Unbathed is the maid, no sparkling water is poured in the city,

Who crosses the river (of death?) utters no . . ,

The wailing priests walk not round about him,

The singer utters no wail,

By the side of the city he utters no lament.(Myth of Enki and Ninhursag, in Kramer, 144f)

In the Babylonian myth of Marduk humans are made to serve the gods:

In “A Bilingual Version of the Creation of the World by Marduk,” man is likewise made for the sake of the gods. There the gods solemnly proclaim Babylon as the dwelling of their hearts’ delight; but, in order to induce them to stay there, Marduk and Aruru create the race of men so that these might attend to the needs of the gods by building their sanctuaries and maintaining their sacrifices. According to a third version . . . humankind was brought into being because the gods desired to have someone to establish the boundary ditch and to keep the canals in their right courses; to irrigate the land to make it produce; to raise grain; to increase ox, sheep, cattle, fish, and fowl; to build sanctuaries for the gods; and to celebrate their festivals. All this man was to do for the benefit of his divine overlords, because “‘the service of the gods” was his ‘‘portion.”’ A similarity to this last tradition is found in the second chapter of Genesis, which mentions as man’s destiny the cultivation of the soil (vs. 5) and the development and preservation of the Garden of Eden (vs. 15). But this work obviously was in his own interest; the Lord God did not ask for any returns. (Heidel, p. 121)

Another story from the same region introduces humanity as wandering nomads apparently leading a brutish life until a god has pity on them and decides to “bring them home” to profitable employment serving the gods.

Nintur was paying attention:

Let me bethink myself of my humankind,

(all) forgotten as they are;

and mindful of mine, Nintur’s, creatures

let me bring them back,

let me lead the people back from their trails.May they come and build cities and cult-places,

that I may cool myself in their shade;

may they lay the bricks for the cult-cities

in pure spots, and

may they found places for divination

in pure spots!(The Eridu Genesis)

From Optimism to Pessimism

Thorkild Jacobsen discusses this text and notes the sharp contrast with the Genesis account of humankind’s beginnings:

In the “Eridu Genesis” moreover the progression is clearly a logical one of cause and effect: the wretched state of natural man touches the motherly heart of Nintur, who has him improve his lot by settling down in cities and building temples; and she gives him a king to lead and organize. As this chain of cause and effect leads from nature to civilization, so a following such chain carries from the early cities and kings over into the story of the flood. The well organized irrigation works carried out by the cities under the leadership of their kings lead to a greatly increased food supply and that in turn makes man multiply on the earth. The volume of noise these people make keeps Enlil from sleeping and makes him decide to get peace and quiet by sending the flood. (p. 140)

and

The “Eridu Genesis” takes throughout, as will have been noticed, an affirmative and optimistic view of existence: it believes in progress. Things were not nearly as good to begin with as they have become since and though man unwittingly, by sheer multiplying, once caused the gods to turn against him; that will not happen again. The gods had a change of heart, realizing apparently that they needed man.

In the biblical account it is the other way around. Things began as perfect from God’s hand and grew then steadily worse through man’s sinfulness until God finally had to do away with all mankind except for the pious Noah who would beget a new and better stock.

The moral judgment here introduced, and the ensuing pessimistic viewpoint, could not be more different from the tenor of the Sumerian tale; only the assurance that such a flood will not recur is common to both. (p. 142)

Heidel, Alexander. The Babylonian Genesis: The Story of Creation. Second edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963.

Jacobsen, Thorkild. “The Eridu Genesis.” In “I Studied Inscriptions from Before the Flood”: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11, edited by Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura, 129–42. Winona Lake, Ind: Eisenbrauns, 2018.

Kramer, Samuel Noah. History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Man’s Recorded History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981.

Sandars, N. K., trans. The Epic of Gilgamesh; Reprinted with revisions. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

One thought on ““Garden of Eden” : Mesopotamian Perspectives”