By the time I finished reading Nanine Charbonnel’s penultimate chapter of Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de papier a queasy sense of déjà vu dragged my mind back decades to a time when I believed that the Bible was a coded book that needed “keys” to open up its true meaning to modern readers. Before Michael Drosnin‘s The Bible Code made its appearance I had memorized all “seven keys” that one particular cult said were required for “understanding the Bible” (according to that cult’s own doctrines, of course). So after I finished reading Nanine Charbonnel’s quite different approach to understanding the nature and origins of the gospels in which she does indeed raise the spectre of authors writing narratives whose meanings are hidden, I had to pause. Had I in one sense come full circle after all these years? What is the difference between Drosnin and Armstrong on the one hand and what Charbonnel [NC] was proposing on the other? Read on and see.

By the time I finished reading Nanine Charbonnel’s penultimate chapter of Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de papier a queasy sense of déjà vu dragged my mind back decades to a time when I believed that the Bible was a coded book that needed “keys” to open up its true meaning to modern readers. Before Michael Drosnin‘s The Bible Code made its appearance I had memorized all “seven keys” that one particular cult said were required for “understanding the Bible” (according to that cult’s own doctrines, of course). So after I finished reading Nanine Charbonnel’s quite different approach to understanding the nature and origins of the gospels in which she does indeed raise the spectre of authors writing narratives whose meanings are hidden, I had to pause. Had I in one sense come full circle after all these years? What is the difference between Drosnin and Armstrong on the one hand and what Charbonnel [NC] was proposing on the other? Read on and see.

The Key of Creative Multilingualism

One man’s fish is another man’s poisson captures in a humorous way what much of midrash is about: word games, double entendres, mixtures of languages. (By the way, that link is to Mal Webb’s page of his recording of the song that I first heard him sing at a Woodford Folk Festival.) The wordplay in gospel midrash is more serious, of course, with its ambiguities in the names and events making up the gospel narratives and their doctrinal themes and innovations.

NC earlier pointed out the multiple layers meaning in the inscription on the cross written in Aramaic, Latin and Greek. Similarly, the stories are told at multiple levels. (Another example: We read of Greeks making their appearance at the final feast of Jesus and are led to recall the prophecy that testifies of the hour the Son of Man is to be glorified — John 12:19-23.) To focus on one passage . . . .

Eli, eli . . .

We are familiar with the last words of Jesus on the cross where he quotes the first line of Psalm 22:

Matthew 27:46-67

About three in the afternoon Jesus cried out in a loud voice, “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?” (which means “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”). When some of those standing there heard this, they said, “He’s calling Elijah.”

Mark 15:34

And at three in the afternoon Jesus cried out in a loud voice, “Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?” (which means “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”). When some of those standing near heard this, they said, “Listen, he’s calling Elijah.”

But scratch the surface and interesting questions appear . . . .

One:

Two divergent religious traditions can be identified by the slight change of rhythm arising from where one places a single accent in one word translated from a Psalm spoken by Jesus on the cross: Depending on where one places the accent of lama (in lama lama sabachthani) we have either the Christian “Why [asking for God’s motivation] have you forsaken me?” spoken by Jesus on the cross or the Jewish “To what end [asking what will be the outcome] have you forsaken me (or exiled us)? The explanatory details of this difference are added at the end of this post.

Two:

There is something more serious: the meaning of the verb. One might be surprised that the phrase transcribed in Matthew’s Greek is “lama sabachtani” and not the Hebrew of the psalm text, i.e. “lama azavtani“? This is because the psalm is in Hebrew, and Matthew’s phrase in Aramaic. But there would be an error of translation, already made by the Septuagint2.

One can think that in the original midrash there was a play on words on this root, allowing the word to be read as meaning either “abandoned” or “glorified”, and that the translator of the Gospel, inspired by the Septuagint, did not see the play on words, and took up the translation of the Septuagint, giving exclusively to “AZaVtaNi” the meaning of “abandoned”.

(Translated from page 434 of Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de papier)

Three:

The authors of Matthew and Mark directly draw our attention to possible misunderstandings arising from similar-sounding words heard in the last words of Jesus on the cross. Jesus speaks the words of the “messiah David” but bystanders mishear him and think he is calling for the prophet Elijah. The author is drawing our attention to confusions arising from languages.

.

NC adds another pun that is indirect but perhaps meaningful: Is not Levi-Matthew the changer, the changer of language? If Matthew is the same as Levi in the Gospel of Mark we find there that he is identified as son of Alphaeus, a name meaning “change” — see one of the Vridar posts on puns in Mark. Here NC takes a glance (in a footnote) at another suggestion by Maurice Mergui:

Immediately after the healing of the paralytic, Jesus-Joshua called on Levi-Matthew.

Mk 2:14 – As he passed by, he saw Levi, the son of Alphaeus, sitting at the customs office, and said to him, “Follow me. And he got up and followed him.

Why is this Levi the son of Alphaeus (from the Hebrew root meaning to change, to switch, to convert money). Son of a money-changer, that should remind us of something. Money changers were among the merchants in the temple. Jesus drove the money changers out of the Temple. He drives their sons, the Levi, out of the Temple. This is (again and again) the leitmotif of the eschatological reversal (The first shall be last) that hides under the guise of an innocuous verse.

As he passed by he saw Levi, the son of Alphaeus, sitting at the customs office

“Passing by” here also means “forgiving” (Hebrew meaning of ‘avar). This is a repeat of the midrash quoted above: the proselytes will marry kohanim and be inside, while the Levites will be outside. At the end of time (but this clause is still absent and the verbs in the present tense) the election will be reversed. The Gentiles will “come in” and you Jews will be out.

(translated from Le Centurion indigne)

The Key of Gospel Emphasis on True Meaning

Plays on the above multilingual ambiguities are readily grasped once we have our attention drawn to them. There are other forms of multiple meanings with special attention directed to the lack of comprehension of outsiders. We find this theme stressed most bluntly in the Gospel of John.

The Gospel of John: staged misunderstandings

The evangelist relishes making the confusion public:

- John 2:19-21 — Exchange with the Jews: Temple is the Body and Rebuilding is the Resurrection (though what happens in the mind of a reader who recalls the metaphor of the people of God being the Temple?)

- John 3:3-4 — Exchange with Nicodemus: Born again is confused with Born from above

- John 4:10 — Exchange with Samaritan woman: running water and living water

- John 4:31 — Exchange with disciples: Food is Doing God’s will

- John 8:33-35 — Exchange with accusers of the adulterous woman: Slavery is subjection to sin

- John 11:11-13 — Exchange with friends of Lazarus: sleep is death

The Key of Narrative Interpretation

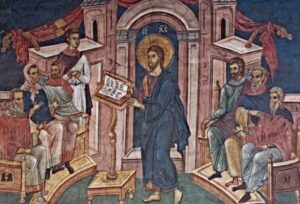

In contrast to the absence of subtlety in the Gospel of John, we find “consummate art” in the Synoptics. Notice Luke 4:21

In contrast to the absence of subtlety in the Gospel of John, we find “consummate art” in the Synoptics. Notice Luke 4:21

Now he began to say to them, ‘Today this scripture is fulfilled in your ears’

Here Jesus (whose name means “God saves”) is presented as reading the very prophet (Isaiah, the name likewise means “God is salvation”) who is the source of Luke’s less obvious agenda. That agenda is to proclaim that the time of the prophets and the accomplishment of the end-time on earth is being taught on this sabbath by the prophet Isaiah through Jesus, “Yahweh saves”. The passage being read is specifically addressing the place of gentiles among God’s people who have been suffering because of their sins, the time when all must be brought together under God. That being the beginning of Jesus’ preaching, the author of the Gospel of Luke draws it all to a fitting closure: Luke 24:27 Continue reading “Are There Really “Keys” to Understanding the New Testament? (Charbonnel continued)”