My earlier posts on M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History were not my favourites. Negatives about assumptions and methods tended to predominate. But I would not want that tone to deflect readers from the many positives and points of interest in the book. Chapter four discusses Jesus’ genealogies in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke in the context of genealogies in ancient literature and culture more generally; chapter five looks at Jesus’ divine parentage in the same contexts. Litwa offers a treasure chest of citations for further informed reading to flesh out many of his points. In this post I only follow up a tiny handful.

My earlier posts on M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History were not my favourites. Negatives about assumptions and methods tended to predominate. But I would not want that tone to deflect readers from the many positives and points of interest in the book. Chapter four discusses Jesus’ genealogies in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke in the context of genealogies in ancient literature and culture more generally; chapter five looks at Jesus’ divine parentage in the same contexts. Litwa offers a treasure chest of citations for further informed reading to flesh out many of his points. In this post I only follow up a tiny handful.

Litwa refers to a work of Plato that mocked as sheer vanity and ignorance the claims of those who prided themselves in being able to trace their family tree back many generations to someone great like Heracles. But Litwa follows this up by evidence that many of the hoi polloi failed to heed Plato’s admonition. The historian Polybius, for example, made it clear that many readers indeed did love to read about lineages that demonstrated a prominent origin of a heroic protagonist. I have followed up the citations Litwa offers quote both views here:

And when people sing the praises of lineage and say someone is of noble birth, because he can show seven wealthy ancestors, he thinks that such praises betray an altogether dull and narrow vision on the part of those who utter them; because of lack of education they cannot keep their eyes fixed upon the whole and are unable to calculate that every man has had countless thousands of ancestors and progenitors, among whom have been in any instance rich and poor, kings and slaves, barbarians and Greeks. And when people pride themselves on a list of twenty-five ancestors and trace their pedigree back to Heracles, the son of Amphitryon, the pettiness of their ideas seems absurd to him; he laughs at them because they cannot free their silly minds of vanity by calculating that Amphitryon’s twenty-fifth ancestor was such as fortune happened to make him, and the fiftieth for that matter. In all these cases the philosopher is derided by the common herd, partly because he seems to be contemptuous, partly because he is ignorant of common things and is always in perplexity.

The historian Polybius confesses he writes for a limited audience in Fragment 9:

For nearly all other writers, or at least most of them, by dealing with every branch of history, attract many kinds of people to the perusal of their works. The genealogical side appeals to those who are fond of a story, and the account of colonies, the foundation of cities, and their ties of kindred, such as we find, for instance, in Ephorus, attracts the curious and lovers of recondite longer, while the student of politics is interested in the doings of nations, cities, and monarchs. As I have confined my attention strictly to these last matters and as my whole work treats of nothing else, it is, as I say, adapted only to one sort of reader, and its perusal will have no attractions for the larger number. I have stated elsewhere at some length my reason for choosing to exclude other branches of history and chronicle actions alone, but there is no harm in briefly reminding my readers of it here in order to impress it on them.

Since genealogies, myths, the planting of colonies, the foundations of cities and their ties of kinship have been recounted by many writers and in many different styles, an author who undertakes at the present day to deal with these matters must either represent the work of others as being his own, a most disgraceful proceeding, or if he refuses to do this, must manifestly toil to no purpose, being constrained to avow that the matters on which he writes and to which he devotes his attention have been adequately narrated and handed down to posterity by previous authors.

You can get a taste of Roman mythical genealogical work from around the era of the gospels at a Classical Texts Library: Hyginus, Fabulae: and another by (Pseudo-)Apollodous on the same site.

But then Litwa reminds us that a post-Pauline letter condemned particular interest in genealogical lines:

Pay no attention to mythoi and endless genealogies (1 Tim. 1:4)

Elite males spent a great deal of time and money “discovering” and advertising their noble ancestors.15

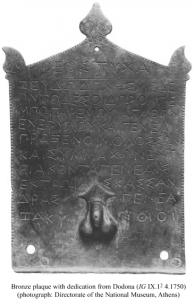

15. The ability of a genealogy to express male (productive) power is highlighted by the presence of a penis with testicles etched onto a genealogical inscription found at Dodona (in western Greece). In this inscription, a certain Agathon of Zacynthus recorded the link of proxeny between himself and the community of Molossians on Epirus through the mythic ancestress Cassandra, the Trojan prophetess. See further P. M. Fraser, “Agathon and Kassandra (IG IX.12 4.1750),” Journal of Hellenic Studies 123 (2003): 26-40

Litwa does not draw attention to the point, but this passage, although post-Pauline, must surely have been penned before our canonical forms of the gospels of Matthew and Luke found wide acceptance. He does, however, point out the close association of myths and genealogies in both this pastoral epistle and in the words of Polybius (quoted above). Good reason underlay the association. Genealogies were very often social constructs (with various tweaks and outright fabrications) to make political points. Litwa explains:

Genealogies show that the line between mythos and historiography is often quite thin. About 100 BCE, the grammarian Asclepiades of Myrlea divided the historical part of grammar into three categories: the true, the seemingly true, and the false. There is only one kind of false history, said Asclepiades, and that is genealogy. It is genealogy that he expressly called “mythic history” (muthike historia). In his system, genealogies were even less true than the stories presented in comedy and mime. (p. 79)

Litwa discusses other historians (Herodotus, Livy, Josephus) and literati (Aristophanes, Hyginus, Cicero) who mocked lofty genealogical claims. Nonetheless, they carried serious import, too, as when the kings of Sparta established their right to rule by tracing their families back to Heracles himself. The Spartans were not alone in such “legitimizing” genealogical claims. Alexander claimed descent from the last native Pharaoh of Egypt, the family of Julius Caesar claimed descent from Aeneas of Troy, and therefore also from the goddess Venus, and so forth. The Roman emperor Galba claimed descent from Jupiter. Another emperor better known to many of us, Vespasian, was well known to have had relatively humble origins and accordingly mocked certain flatterers who attempted to assign a lineage back to Heracles.

What of that “little problem” in the gospels that trace Jesus’ genealogy through to Joseph who was not, according to the story, the literal father of Jesus? No problem, Litwa points out:

Yet when we compare other mythic genealogies, these kinds of hitches did not seem bothersome to the ancients. The Greek biographer Plutarch, for instance, fleshed out the genealogy of Alexander the Great. Plutarch recorded the common tradition that Alexander, through his father, Philip, was a descendant of the god Heracles. One would think that this impressive genealogy would be ruined by the fact that, according to widespread perception—and Plutarch’s own report—Philip was not Alexander’s biological father. Plutarch himself narrated that Zeus impregnated Alexander’s mother, Olympias; and Olympias supposedly acknowledged this point directly to the adult Alexander.

Yet these conflicting reports did not seem to impose cognitive dissonance. A concept of dual paternity was possible. As most people in the ancient world knew (and perhaps believed on some level), Alexander’s real father was the high God Zeus, though he was also the “son of Philip.” (p. 84)

Litwa suggests that the evangelists responsible for the genealogies of Jesus in our Gospels of Matthew and Luke were creating a “mythic historiography” that had a strong appeal to certain readers and served to exalt the status of Jesus in a way comparable to the myths or legends associated with other potentates.

And yet the point of a genealogy is to show that an author was at least trying– despite innacuracies — to use the tropes of historiography. (p. 79)

Divine Conception

After the above, this Jew of Celsus, as if he were a Greek who loved learning, and were well instructed in Greek literature, continues: “The old mythological fables, which attributed a divine origin to Perseus, and Amphion, and Aeacus, and Minos, were not believed by us. Nevertheless, that they might not appear unworthy of credit, they represented the deeds of these personages as great and wonderful, and truly beyond the power of man; but what hast thou done that is noble or wonderful either in deed or in word? Thou hast made no manifestation to us, although they challenged you in the temple to exhibit some unmistakeable sign that you were the Son of God.”

(Contra Celsum 1:67)

Heroes were almost by definition descended from divinities. Litwa refers to a select few Greek names that are actually taken directly from Celsus’s cynical comparison with Jesus (Contra Celsum 1.67): Perseus, Amphion, Aeacus, Minos. Litwa reminds us of Origen’s record of Celsus attempting to argue that Jesus was no different in this respect from other mythical figures. Here I think Litwa is quite correct (as he also is in his view of the inspiration for the genealogies of Jesus) when he writes:

It is not that the evangelists borrowed from the stories of Perseus, Heracles, or Minos to present their idea of divine conception. Stories of divine conception were culturally common coin in the ancient Mediterranean world and could be independently imagined and updated in distinct ways. (p. 87, my emphasis)

Here I think Litwa trips over his earlier criticism of one particular point by Richard Carrier, the relevance of the Rank-Raglan hero classification. In chapter one Litwa wrote (pp. 35-37):

The Hero Pattern

Carrier frequently appeals to what is called “the hero pattern.” This pattern was explored by Otto Rank in Germany (1909) and more thoroughly by Lord Raglan in England (1934). Raglan’s pattern includes twenty-two events in a kind of abstract heroic “life”:

1. The hero’s mother is a royal virgin.

2. His father is a king and

3. Often a near relative of his mother.

4. The circumstances of his conception are unusual, and

5. He is also reputed to be the son of a god.

6. At birth an attempt is made, usually by his father or his maternal grandfather, to kill him, but

7. He is spirited away and

8. Reared by foster parents in a far country,

9. We are told nothing of his childhood, but

10. On reaching manhood, he returns or goes to his future kingdom.

11. After a victory over the king and/or a giant, dragon, or wild beast,

12. He marries a princess, often the daughter of his predecessor, and

13. Becomes king.

14. For a time he reigns uneventfully and

15. Prescribes laws, but

16. Later he loses favor with the gods and/or his subjects and

17. Is driven from the throne and city, after which

18. He meets with a mysterious death,

19. Often at the top of a hill.

20. His children, if any, do not succeed him.

21. His body is not buried, but nevertheless

22. He has one or more holy sepulchers.Although it is enticing to apply this pattern to Jesus (a task that Raglan avoided but that Carrier takes up), its theoretical value is questionable. Even if it gives an air of universality, this pattern is hardly cross-cultural. It is based on European heroes and specifically the myth of Oedipus. Raglan based his work on James George Frazer’s notion that a king-killing ritual lies behind the pattern. Yet such a cross-cultural ritual never seems to have existed.

There are yet deeper problems. Although no hero perfectly conforms to the pattern, the pattern itself encourages mythicists to hunt for similarities between incredibly wide-ranging figures, skating over differences based on locality, time, and culture. Claimed similarities are sometimes forced (the fudge factor). Carrier avers, for instance, that though Jesus failed to marry a princess, he took the church as his bride. Yet here we are on the level of Christian allegory, at second remove from the gospel stories.

In the case of Jesus, moreover, the pattern ignores major elements of his life. What would Jesus be without his incarnation, his works of wonder, the resurrection, and so on? Other elements of Raglan’s pattern contradict the gospel accounts. Jesus’s mother was a peasant. His father or grandfather did not try to kill him. He was not raised by foster parents. Jesus did not attain his kingdom on earth (in one version, he denied that his kingdom was of this world; John 18:36). He did not lose favor among those who killed him. His killers, depicted as elite Jews and Romans, never actually favored him. Finally, all gospel stories agree that Jesus was buried.

It is unlikely, then, that the gospel writers thought of this or any other holistic pattern to construct their narratives about Jesus. Instead, they called to mind their own native (Jewish) mythology. If there is any mythology historically connected to early Christian mythology, most scholars would opt for Jewish lore. Yet in this case we encounter the same problem. No matter how similar two stories may be, we do not know if story “x” ever caused Christian story “y”—and it is simplistic to think so.

Everything about Litwa’s argument here is strained and simply lacking fundamental appreciation of the significance of the Rank-Raglan model, apparently the spinoff of a determined effort to undermine Richard Carrier’s application of it to Jesus. Let’s forget Carrier and just return to the RR model itself. RR did not suggest by any means that any author was somehow consciously, deliberately, attempting to make a hero figure conform to such a list of characteristics. RR never suggested that literature was filled with figures who conformed to virtually every point in the list. And Carrier himself explicitly said his allegorical analogies were mere asides and not central to his argument. (See a fuller discussion in Review, part 2 (Damnation upon that Christ Myth Theory!) : How the Gospels Became History / Litwa. No, the RR model applies culturally — exactly as Litwa himself argues for the influence of other cultural phenomena. To repeat Litwa’s own words with appropriate modification:

It is not that the evangelists borrowed from the stories of [heroes fitting a certain type of characteristics identified by Rank-Raglan]. Stories of [such figures] were culturally common coin in the ancient Mediterranean world and could be independently imagined and updated in distinct ways. (p. 87)

Origen’s Celsus expressed his criticism with vivid crudity (Contra Celsum 1:39):

I do not think it necessary to grapple with an argument advanced not in a serious but in a scoffing spirit, such as the following: “If the mother of Jesus was beautiful, then the god whose nature is not to love a corruptible body, had intercourse with her because she was beautiful. . . ”

Here Litwa responds with the interesting detail that by the time of the Christian writings there were alternative “philosophical” notions of divine conception. Litwa, page 88,

As attitudes toward divine sex changed by the first century CE, so did stories told about divinely caused births.

If the evangelists bypassed Plato’s words on the relevance of genealogies being traced back to great heroes and divinities, they certainly conformed with Platonic thought when it came to the divine conception of Jesus. Taking up Litwa’s citation of a passage from Plutarch I quote a section of Table Talk, VIII, 717-718:

Tyndares the Lacedaemonian replied, “ It is fitting to celebrate Plato with the line,

He seemed the scion not of mortal man, but of a god.

But I suspect that begetting is no less inconsistent with the immortality of the divine than is being begotten. For it, too, is a kind of change, and a vicissitude. . . . I am reassured when I hear Plato himself naming the uncreated and eternal god as the father and maker of the cosmos and of other created things. They were created not through semen, surely ; it was by a different potency that God begot in matter the principle of generation, under whose influence it became receptive and was transformed.

[A quote from Sophocles] Sophocles seems to be alluding to the notion that “wind-eggs” (laid without previous copulation) were the result of impregnation of the female by the winds. (The “passing of the winds” is through the hen’s body.). . . . Plutarch is, of course, comparing the hen’s unawareness with that of a mortal woman impregnated in a mystical or spiritual way, by a god. (Loeb edition pages 116-117)

The hen knows not the passing of the winds.

Except when brooding-time is near.And I do not find it strange if it is not by a physical approach, like a man’s, but by some other kind of contact or touch, by other agencies, that a god alters mortal nature and makes it pregnant with a more divine offspring.

Many readers will be aware that the word for wind in the gospels is pneuma, a word that can also be translated as breath or spirit. Plutarch, likewise, uses the same word in both senses in his works.

When Plutarch wrote his Life of Numa and was obliged to explain a myth that he had fathered a child through a goddess, Plutarch was emphatic that the goddess was not by any means succumbing to any kind of physical lust. Like Mary, it was his virtue that made him favoured by a deity:

And there is some reason in supposing that Deity, who is not a lover of horses or birds, but a lover of men, should be willing to consort with men of superlative goodness, and should not dislike or disdain the company of a wise and holy man. But that an immortal god should take carnal pleasure in a mortal body and its beauty, this, surely, is hard to believe.

Litwa is right to note the coherence of these ideas with Luke 1:35

The angel answered, “The Holy Spirit will come on you [Mary], and the power of the Most High will overshadow you. So the holy one to be born will be calledthe Son of God. . . .”

How does wind or breath or spirit come to replace semen as the begetting agent? Here Litwa finds the answer in Aristotle. Aristotle asked what it was about the semen that produced generation and concluded that semen contains something spiritual, a spiritual power:

Supposing it is true that the semen which is so introduced is not an ingredient in the fetation which is formed, but performs its function simply by means of the dynamis which it contains. . . . .

In all cases the semen contains within itself that which causes it to be fertile—what is known as “hot” substance which is not fire nor any similar substance, but the pneuma which is enclosed within the semen or foam-like stuff, and the natural substance which is in the pneuma ; and this substance is analogous to the element which belongs to the stars. (Generation of Animals, II. 736-739)

Litwa is not suggesting that the evangelists themselves directly turned to Aristotle for the idea but rather that Aristotle’s influence was more broadly cultural:

This is not an argument that the evangelist “borrowed” from Plutarch or from other historicized Greek myths. The similarities between Luke and Plutarch are not due to a genetic link but to a shared intellectual culture. It was a common, culturally shaped set of theological conceptions that shaped what would be appropriate and plausible in a story of divine conception. (p. 92)

Litwa acknowledges the clear debt Luke’s nativity story has to well-known narratives of Sarah and Hannah in the Jewish scriptures. The most he can allow for the influence of ideas about the way divinities could beget humans without direct sexual intercourse (as we have seen explained in Plutarch) is that “Luke” “indirectly and subconsciously emulate[d] Greek mythic templates.” No doubt. I am sure Litwa is correct. The evangelists were products of their time. Judaism was not hermetically sealed off from the broader Greco-Roman culture.

If the genealogies of other past heroes and current rulers raised questioning eyebrows among more sophisticated readers of the day, the way Jesus was divinely conceived was at least compatible with sophisticated explanations for traditions that past greats like Plato had been divinely conceived. Satirists like Lucian mocked the notion expressed so seriously by Plutarch but the evangelists evidently considered it passable fare for their readers.

Litwa’s larger argument is that the gospel narratives conformed to widespread ideas of what was often expected in historical works and of what were considered plausible explanations for certain miraculous tales. I have attempted to present as fairly and fully as is reasonable in a blog essay Litwa’s arguments and I do find the details fascinating. Whether Litwa’s larger argument can be sustained I will leave to the consideration of those who read the information he sets out.

| To order a copy of How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths at the Footprint Books Website with a 15% discount click here or visit www.footprint.com.au

Please use discount voucher code BCLUB19 at the checkout to apply the discount. |

Litwa, M. David. 2019. How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Again, of course, all of this is steeped in blood magic.

I have read a great deal of history and it is a very rare occurrence that greatness, as bestowed by history ran in families: the few I can think of were Winston Churchill’s line, William James and his immediate family, maybe the Darwins’.

Also, if one traces one genealogy back seven generations to someone famous and one is a tailor, do we hear about that? Probably not. The genealogy argument is almost always made by someone begging for some reflected glory.

As always, sir, your posts are interesting and thought provoking. I wish you a healthy and prosperous new year!

Thank you for your wishes. I’ve had a bit of bad luck lately — health, family and even freak tech issues have conspired to keep me absent from writing longer than I ever wanted. Best wishes to you and all readers.

To add to Litwa’s stuff on divine conception:

King and Messiah as Son of God: Divine, Human, and Angelic Messianic Figures(Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2008), Adela Yarbro Collins, John J. Collins

It seems Io may have been a virgin. Io’s son Epaphos was said to be the same as Apis/Osiris. The Apis bull was born to a virgin cow.

Wandering in Ancient Greek Culture(University of Chicago Press, 2005), Silvio Montiglio

Theophrastus of Eresus: Sources on biology(Brill, 1994), Robert Sharples, Pamela M. Huby, William Wall Fortenbaugh

Glad you mentioned the light of the moon touch. I had removed references to that aspect to try to limit the length of the post.

Tag: Midrash

About the Divine Conception: The book of Ruth

Luke 1

30 Then the angel said to her, “Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God.

Ruth 3

11 And now, my daughter (Ruth), do not fear. I (Boaz ) will do for you all that you request, for all the people of my town know that you (Ruth) are a virtuous woman

Luke 1

35 And the angel answered and said to her, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Highest will overshadow you;

Luke 1

38 Then Mary said, “Behold the maidservant of the Lord! Let it be to me according to your word.”

Ruth 3

9 And he (Boaz ) said, “Who are you?” So she answered, “I am Ruth, your maidservant. Take your maidservant under your wing,

Tag: Midrash

About the genealogy:

Matthew 1

5 Salmon begot Boaz by Rahab, Boaz begot Obed by Ruth, Obed begot Jesse,

6 and Jesse begot David the king.

To return to ‘Numa’ ch.4 : “Yet the Egyptians make a distinction they think not implausible that while it is not impossible for a spirit of a god to come close to a woman and make her pregnant..” Plutarch uses the present tense to indicate a belief held by some (not by himself) to be a current possibility. Who the ‘Egyptians’ might be is unspecified.

An intriguing tale occurs in Plutarch’s ‘Lysander’ ch.26, regarding the general’s attempt to change the Spartan lawcode to enable him to qualify for kingship. Entirely sceptical and hypothetical- it is a plan, never executed, alleged against Lysander post mortem- it nevertheless demonstrates Plutarch’s conception of what sufficient people in his time were prepared to believe and act upon, not just those of the fifth century:, given his presupposition of cultural continuity in the cult at Delphi :

“There was a woman in Pontus who declared that she was pregnant by Apollo. Many disbelieved her, as was natural, but many also accepted it, so that many notable persons took an interest in his upbringing. ..Lysander manipulated many distinguished champions of the tale, who brought the story of the boy’s birth into credit without raising suspicion. They also brought back another response from Delphi [planted by Lysander], and caused it to be circulated in Sparta, which declared that sundry very ancient oracles were kept in secret writings by the priests there, and that it was not possible to get these, nor even lawful to read them, unless someone born of Apollo should come after a long lapse of time, give the keepers an intelligible token of his birth, and obtain the tablets containing the oracles [forged by Lysander]. The way being thus prepared, Silenus [the boy, by now a young man] was to come and demand the oracles as Apollo’s son, and the priests who were co-conspirators were to insist on precise answers to all their questions about his birth, and finally ‘persuaded’ that he was the son of Apollo, were to show him the writing. Then Silenus..was to read aloud the prophecies, especially the one relating to the kingdom, for the sake of which the whole scheme had been invented…”