My earlier posts on M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History were not my favourites. Negatives about assumptions and methods tended to predominate. But I would not want that tone to deflect readers from the many positives and points of interest in the book. Chapter four discusses Jesus’ genealogies in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke in the context of genealogies in ancient literature and culture more generally; chapter five looks at Jesus’ divine parentage in the same contexts. Litwa offers a treasure chest of citations for further informed reading to flesh out many of his points. In this post I only follow up a tiny handful.

My earlier posts on M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History were not my favourites. Negatives about assumptions and methods tended to predominate. But I would not want that tone to deflect readers from the many positives and points of interest in the book. Chapter four discusses Jesus’ genealogies in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke in the context of genealogies in ancient literature and culture more generally; chapter five looks at Jesus’ divine parentage in the same contexts. Litwa offers a treasure chest of citations for further informed reading to flesh out many of his points. In this post I only follow up a tiny handful.

Litwa refers to a work of Plato that mocked as sheer vanity and ignorance the claims of those who prided themselves in being able to trace their family tree back many generations to someone great like Heracles. But Litwa follows this up by evidence that many of the hoi polloi failed to heed Plato’s admonition. The historian Polybius, for example, made it clear that many readers indeed did love to read about lineages that demonstrated a prominent origin of a heroic protagonist. I have followed up the citations Litwa offers quote both views here:

And when people sing the praises of lineage and say someone is of noble birth, because he can show seven wealthy ancestors, he thinks that such praises betray an altogether dull and narrow vision on the part of those who utter them; because of lack of education they cannot keep their eyes fixed upon the whole and are unable to calculate that every man has had countless thousands of ancestors and progenitors, among whom have been in any instance rich and poor, kings and slaves, barbarians and Greeks. And when people pride themselves on a list of twenty-five ancestors and trace their pedigree back to Heracles, the son of Amphitryon, the pettiness of their ideas seems absurd to him; he laughs at them because they cannot free their silly minds of vanity by calculating that Amphitryon’s twenty-fifth ancestor was such as fortune happened to make him, and the fiftieth for that matter. In all these cases the philosopher is derided by the common herd, partly because he seems to be contemptuous, partly because he is ignorant of common things and is always in perplexity.

The historian Polybius confesses he writes for a limited audience in Fragment 9:

For nearly all other writers, or at least most of them, by dealing with every branch of history, attract many kinds of people to the perusal of their works. The genealogical side appeals to those who are fond of a story, and the account of colonies, the foundation of cities, and their ties of kindred, such as we find, for instance, in Ephorus, attracts the curious and lovers of recondite longer, while the student of politics is interested in the doings of nations, cities, and monarchs. As I have confined my attention strictly to these last matters and as my whole work treats of nothing else, it is, as I say, adapted only to one sort of reader, and its perusal will have no attractions for the larger number. I have stated elsewhere at some length my reason for choosing to exclude other branches of history and chronicle actions alone, but there is no harm in briefly reminding my readers of it here in order to impress it on them.

Since genealogies, myths, the planting of colonies, the foundations of cities and their ties of kinship have been recounted by many writers and in many different styles, an author who undertakes at the present day to deal with these matters must either represent the work of others as being his own, a most disgraceful proceeding, or if he refuses to do this, must manifestly toil to no purpose, being constrained to avow that the matters on which he writes and to which he devotes his attention have been adequately narrated and handed down to posterity by previous authors.

You can get a taste of Roman mythical genealogical work from around the era of the gospels at a Classical Texts Library: Hyginus, Fabulae: and another by (Pseudo-)Apollodous on the same site.

But then Litwa reminds us that a post-Pauline letter condemned particular interest in genealogical lines:

Pay no attention to mythoi and endless genealogies (1 Tim. 1:4)

Elite males spent a great deal of time and money “discovering” and advertising their noble ancestors.15

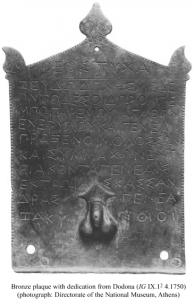

15. The ability of a genealogy to express male (productive) power is highlighted by the presence of a penis with testicles etched onto a genealogical inscription found at Dodona (in western Greece). In this inscription, a certain Agathon of Zacynthus recorded the link of proxeny between himself and the community of Molossians on Epirus through the mythic ancestress Cassandra, the Trojan prophetess. See further P. M. Fraser, “Agathon and Kassandra (IG IX.12 4.1750),” Journal of Hellenic Studies 123 (2003): 26-40

Litwa does not draw attention to the point, but this passage, although post-Pauline, must surely have been penned before our canonical forms of the gospels of Matthew and Luke found wide acceptance. He does, however, point out the close association of myths and genealogies in both this pastoral epistle and in the words of Polybius (quoted above). Good reason underlay the association. Genealogies were very often social constructs (with various tweaks and outright fabrications) to make political points. Litwa explains:

Genealogies show that the line between mythos and historiography is often quite thin. About 100 BCE, the grammarian Asclepiades of Myrlea divided the historical part of grammar into three categories: the true, the seemingly true, and the false. There is only one kind of false history, said Asclepiades, and that is genealogy. It is genealogy that he expressly called “mythic history” (muthike historia). In his system, genealogies were even less true than the stories presented in comedy and mime. (p. 79)

Litwa discusses other historians (Herodotus, Livy, Josephus) and literati (Aristophanes, Hyginus, Cicero) who mocked lofty genealogical claims. Nonetheless, they carried serious import, too, as when the kings of Sparta established their right to rule by tracing their families back to Heracles himself. The Spartans were not alone in such “legitimizing” genealogical claims. Alexander claimed descent from the last native Pharaoh of Egypt, the family of Julius Caesar claimed descent from Aeneas of Troy, and therefore also from the goddess Venus, and so forth. The Roman emperor Galba claimed descent from Jupiter. Another emperor better known to many of us, Vespasian, was well known to have had relatively humble origins and accordingly mocked certain flatterers who attempted to assign a lineage back to Heracles.

What of that “little problem” in the gospels that trace Jesus’ genealogy through to Joseph who was not, according to the story, the literal father of Jesus? No problem, Litwa points out:

Yet when we compare other mythic genealogies, these kinds of hitches did not seem bothersome to the ancients. The Greek biographer Plutarch, for instance, fleshed out the genealogy of Alexander the Great. Plutarch recorded the common tradition that Alexander, through his father, Philip, was a descendant of the god Heracles. One would think that this impressive genealogy would be ruined by the fact that, according to widespread perception—and Plutarch’s own report—Philip was not Alexander’s biological father. Plutarch himself narrated that Zeus impregnated Alexander’s mother, Olympias; and Olympias supposedly acknowledged this point directly to the adult Alexander.

Yet these conflicting reports did not seem to impose cognitive dissonance. A concept of dual paternity was possible. As most people in the ancient world knew (and perhaps believed on some level), Alexander’s real father was the high God Zeus, though he was also the “son of Philip.” (p. 84)

Litwa suggests that the evangelists responsible for the genealogies of Jesus in our Gospels of Matthew and Luke were creating a “mythic historiography” that had a strong appeal to certain readers and served to exalt the status of Jesus in a way comparable to the myths or legends associated with other potentates.

And yet the point of a genealogy is to show that an author was at least trying– despite innacuracies — to use the tropes of historiography. (p. 79)

Divine Conception

Continue reading “Review, part 5 (Litwa on) Jesus’ Genealogy and Divine Conception”