The king is a what?

The king is a what?

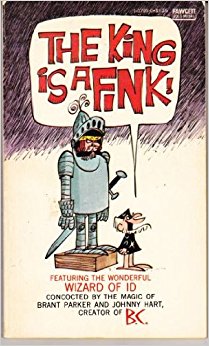

We had finally made an end-to-end connection from an automated teller machine (ATM), through our alarm-correlation engine, and into our trouble-ticketing system. Actually, we probably simulated something like a paper jam, but the free text description that went along with that alarm type contained this message: “The King Is a Fink!”

Why? We were following an old tradition. At NCR, it signified a successful test. Over at HP, I’m told, they would transmit the sentence, “My hovercraft is full of eels!” So I suppose their chief engineer liked to watch Monty Python, while NCR’s enjoyed the comic strip, The Wizard of Id.

It was the late 1990s, and I was a contractor visiting the development team in Copenhagen, Denmark. They had other traditions there, too. Later that afternoon, we celebrated our success in the break room, where they offered me truly awful champagne (deliberately so) and some bright pink marshmallow peeps. I declined the peeps, having become a vegetarian ten years earlier.

At some point during the celebration, somebody asked to nobody in particular, “What is a fink?” I paused to think about that one. How would you define that word in terms a Dane or, for that matter, any non-English speaker would understand? My mind wandered to “Rat Pfink a Boo Boo” — and how would you ever explain that?

Before I could answer, a Danish woman who had spent her teens in the U.S. said, “It’s a bird. It’s supposed to be a ‘finch.’ The king is a finch.” Some nodded. Others were still perplexed. After all, why would you compare a monarch to a bird?

I stepped in and politely said, “No. It’s fink.” And I tried to explain the comic strip to them.

Cultural context

I relate this story to point out the importance of cultural context. Imagine you’re a Brazilian trying to get a networked laser printer to work out in the Amazon jungle, with no access to the Internet. You finally get that first sheet of paper to crank out, and it says, “My hovercraft is full of eels!” If you didn’t know English, you might be tempted to look up each word. And you might eventually get the mental picture of a hovercraft — that’s full of eels. You would be right if you said to yourself, “I have no idea what that means.”

But your colleague who learned English at the university and who actually knows quite a bit about nautical craft and sea creatures says he knows exactly what it means. He invents a complex story that seems to make narrative sense, but is completely wrong. The truth is, you both lack the cultural context to understand that it comes from a comedy sketch and, further, that in the HP environment, it’s just a funny, nonsensical thing to say.

Neither of you knows what the sentence means, but the person with more supposedly relevant information has much more confidence in his wrong explanation. Please understand that I’m not bemoaning the fact that both of you are wrong. When you said, “I don’t know,” you were right. In cases with insufficient information, admitting our ignorance pending more information is the correct response.

Linguistic knowledge vs. cultural knowledge

Understanding text requires both the knowledge of the mechanics of language and an understanding of the culture that produced it. Unfortunately, in NT studies our understanding of the mechanics of Koine Greek is far greater than our understanding of the culture that produced the gospels, the epistles, or John’s apocalypse.

Consider, for example, Paul’s use of the term “spiritual body” in 1 Cor. 15:44b:

Εἰ ἔστιν σῶμα ψυχικόν, ἔστιν καὶ πνευματικόν.

If there is a body physical, there is also spiritual [body].

Linguistically, it’s clear. Theologically, it isn’t. Biologically, it’s pure gibberish.

I assume Paul knew exactly what he meant by a spiritual body. But I don’t assume that my understanding of that Greek sentence necessarily equates to my knowing what Paul meant.

On the other hand, NT scholars will likely know the history of the Church’s understanding of the term — far more than I would ever care to learn. But such a deep theological understanding can sometimes be a liability for the rational historian. The Church, after all, needed to harmonize the disparate views of the resurrected human corpse. If the body is raised in spiritual perfection, then why was Jesus still wounded? If the resurrected body is physical, then how did Jesus walk through solid walls? The notion that there is only one answer that explains everything is a deadly fallacy. It’s apologetics, and, consequently, anti-rational history.

In addition, scholars have spent untold semester hours of Greek language instruction. You don’t even have to ask them. Unprompted, they’ll gladly tell you how much they know about ancient languages, and how that alone makes them professional experts with insights and understanding you can’t hope to approach. But that very expertise makes them vulnerable to the illusion that they know more than they can know, and to assert that their interpretation of the text is plain, obvious, or even indisputable.

The point

To be clear, I’m not asking readers for comments explaining what Paul’s “spiritual body” is supposed to mean. Thanks to the Internet, the doctrinal debates over the nature of bodily resurrection are at our fingertips. Instead I’m asking you to consider mental errors and fallacies to which we are all vulnerable, but which seem to disproportionately plague scholars of the Bible. In the coming few posts, we’ll look at them.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

It’s an example of a meme which predates the Internet. Internet memes are a definitive form of cultural expression and those who dismiss them are uncouth.

As an engineer, I know that a truly good troubleshooter knows how to get to the bottom of a mystery and does not stop at an answer that polishes his reputation but is, as you say, wrong. But most engineers are not good at troubleshooting and most average people think they could solve a mystery because they watch TV. If presented with an actual mystery they wouldn’t know where to start, but what they actually do is deny there is a problem so they don’t have to investigate and discover what they don’t want to be true.

And then there’s Dank Christian Memes, a hilarious pool of oblivious cringe. Christianity has never been a culture. Christians don’t know what culture is. All the great art that came out of Christianity had to wait for the Renaissance when Christian power began to decline. Within the culture vacuum of Christianity is a constant desperation to make Christianity seem cool to the kids because the kids are the ones leaving never to return. First they said rock and roll was of Satan, then they made awful Christian Rock bands because they were losing the kids, then they said drugs were bad, then they made Dank Christian Memes because they were losing the kids. They are still losing the kids, the kids are just laughing as they go.

Most people aren’t good at troubleshooting, because we’re wired to look for confirmatory evidence. Even trained engineers will jump to conclusions and get stuck in tunnel vision. If they accidentally find the answer quickly, it will reinforce bad habits. They can’t tell when they’re lucky or when they’re good.

There’s more to my story above, BTW. We celebrated prematurely, and the problem, as it turned out, was something I had to fix with chewing gum and baling wire. Once the problem manifested itself, I realized it was completely obvious. I should have predicted it. However, none of us had foreseen the issue. It’s hard to imagine all the ways things can go wrong.

One of my largest clients front line product is coming to the end of its life, quickly, and they hired someone who seems to have no skill or experience to develop the replacement. A lot of my clients are like this and they disappear never to be heard from again. This is one of my largest clients, not some two bit startup. If this person fails it will hurt a lot of people.

Tim, your post was totally worth it, just for the ‘Rat Pfink a Boo Boo’ link.

It made me wonder what a philologist from Rigel would make of these two, perfectly good, Pre-Nuclear Holocaust English.

Time flies like an arrow.

Fruit flies like a banana.

One is a metaphorical expression and one is a bare statement of fact. But which is which? The partial or total loss of cultural context renders even the most apparently straightforward expressions problematic.

The fundamental error, imo, is assuming prima facie that any document was written by who the document purports and when it purports.

I’m with Bauer that 1 Corinthians is a 2nd century work that deals with 2nd century issues. One can’t begin to grasp what the author meant by a spiritual resurrected body, without addressing who was denying resurrection (15:12) and why.

One must entertain that 1 Cor. 15 is an attempt to amalgamate two competing eschatologies — a purely physical, vs. a purely spiritual, resurrection. To continue with the techie analogy, 1 Cor. 15 is a kludge.

Fortunately for today’s scholars, they will never have read Bauer or be confused by him.

LOL. Or confuse him with Baur.

Just First Corinthians or the whole Pauline oeuvre? Having the Epistles post-date the Gospels highlights Epistilotary ignorance of the Gospel Jesus even more. This hypothesis appears to create more problems than it solves.