What’s in a name?

And because of my father, between the ages 7 through 15, I thought my name was “Jesus Christ.” He’d say, “JESUS CHRIST!” And my brother, Russell, thought his name was “Dammit.” “‘Dammit, will you stop all that noise?! And Jesus Christ, SIT DOWN!” So one day I’m out playing in the rain. My father said “Dammit, will you get in here?!” I said, “Dad, I’m Jesus Christ!”

–Bill Cosby

In his new book, Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? (which Jim West with no trace of irony calls “excellent”), Maurice Casey makes it abundantly clear that Neil and I should get off his lawn. We should also slow down and, for heaven’s sake, turn out the lights when leaving a room.

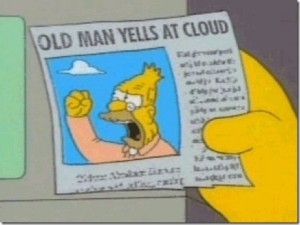

Maurice Casey: Old Yeller

Since my chief purpose here is not to make fun of such a charming and erudite scholar as Dr. Casey, I’ll say just one thing about the shameful way a famous scholar lashes out at amateurs on the web. Lest any reader out there get the wrong idea, my first name is not Blogger. Same for Neil.

I will instead, at least for now, ignore the embarrassing, yelling-at-cloud parts of this dismal little book and focus on Mo’s evidence for the historical Jesus.

If I had a hammer

“I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

–Abraham Maslow

Casey, you will recall, has written several books on biblical studies. He’s justly recognized as an expert in the Aramaic language. In fact, he is probably the foremost living expert on Aramaic, especially with respect to its historical roots, its evolution, its variants, and its use in first-century Palestine. I own most of his books on the subject, and although I disagree with many of his dogmatic conclusions, his basic research is thorough and generally reliable.

The problem I have with Casey is that his prodigious knowledge of Aramaic causes him to see everything in the New Testament from that perspective. He frequently reminds me of Catherwood in the Firesign Theatre’s “The Further Adventures of Nick Danger,” who, upon returning from the past in his time machine, shouts:

I’m back! It’s a success! I have proof I’ve been to ancient Greece! Look at this grape!

Casey’s hammer is Aramaic monomania. He believes that simply uncovering the Aramaic underpinnings of the NT conclusively proves Jesus’ historicity. I’m not exaggerating. For example, he cites the Aramaic magic words in Mark that Jesus used to raise Jairus’s daughter. His research shows that Mark’s original (mis)spelling without the “i” — talitha koum — probably reflects the actual pronunciation by Aramaic speakers.

Moreover, I have followed the reading of the oldest and best manuscripts. The majority of manuscripts read the technically correct written feminine form koumi, but there is good reason to believe that the feminine ending ‘i’ was not pronounced. It follows that Talitha koum is exactly what Jesus said. (p. 45, bold emphasis mine)

Maurice Casey: Step-Skipper

Casey’s Postulate: Mark was bilingual. Therefore Jesus existed and we know exactly what he said.

Time for a little Kids in the Hall break.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uA_3MnVen08]

. . .

[@2:46] Gavin: My dad and I? One time? One summer? We built a veranda? Without any tools. Therefore I should paint your chair.

It is unclear why Gavin’s ability to build a veranda without tools should convince us to let him paint a chair. Similarly, it is unclear why the fact that Mark may have known the correct pronunciation of “koumi” means that Jesus really said it. How does Casey get from point A to point Z without touching any point in between?

An angry Jesus?

We will find Casey’s analysis of Mark 1:40-45 quite useful for understanding his monomaniacal method.

Again, at the beginning of a healing narrative, some old manuscripts have Mark say that Jesus ‘was angry’ (orgistheis), which makes no sense at all.

Actually, it makes a great deal of sense, if he had only read Bart Ehrman’s “A Leper in the Hands of an Angry Jesus” (in New Testament Greek and Exegesis: Essays in Honor of Gerald F. Hawthorne), a masterpiece of textual criticism and biblical exegesis. Unlike Casey, Ehrman carefully analyzed the evidence from all quarters and concluded that Mark’s original text had orgistheis/ὀργισθεὶς, and that he meant it.

At the risk of oversimplifying his argument (you really should read it), here’s Ehrman’s conclusion.

Jesus is approached by a leper who says, “If you are willing, you are able to cleanse me.” But why would Jesus not be willing to heal him? Of course he is willing, just as he is authorized and able. Jesus is angered — not at the illness [a common apologetic approach], or the world, or the law, or Satan — but at the very idea that anyone would question, even implicitly, his willingness to help one in need. He heals the man before rebuking him and throwing him out. (p. 95, bold emphasis mine)

Casey continues:

Most manuscripts of Mark accordingly read ‘had compassion’ (splanchnistheis), which is what copyists would much have preferred to read. Matthew and Luke both leave the word out, which makes good sense only if they both read orgistheis too. (p. 45)

He’s absolutely correct. Not only did Matthew and Luke (whom Ehrman calls the “first copyists” of Mark) leave it out, but the evidence strongly indicates that the Diatessaron retained Jesus’ anger, meaning that Tatian followed the original text of Mark. Again, quoting Ehrman:

Some hard evidence exists in the present case. From the fourth century, Ephrem’s commentary on Tatian’s Diatessaron (produced in the 2d century) discusses that when Jesus met the leper he “became angry.” If the Diatessaron did have this reading, then it is the earliest witness that we have . . . (p. 80, bold emphasis mine)

And now Casey’s monomania takes over.

The Aramaic regaz, however, means both ‘be angry’ and ‘be deeply moved’, which makes perfect sense. (p. 45, emphasis added)

Here Casey is signalling that his argument is weak. We may call this a “Mo-tell.” Whenever he’s about to skate out on thin logical ice, he will use the word “perfect” or “perfectly.” He will write such-and-such “fits perfectly” or so-and-so “makes perfect sense.”

Casey concludes from his “perfect” explanation:

It follows that this is a mistake typical of bilingual translators, who suffer from interference. This is one of many pieces of evidence that parts of Mark’s Gospel were translated from Aramaic sources.

He repeats himself several pages later, adding this astonishing preface:

Here again Mark’s Greek is perfectly comprehensible as a literal and unrevised translation of an Aramaic source which gave a perfectly accurate albeit very brief account of an incident which really took place. (p. 58, emphasis added)

Wow. It “really took place.” It’s as if we’re watching history being perfectly invented right before our very eyes!

A snorting Jesus

Sadly, Casey has proved nothing except the fact that he has not kept up with Markan literature. He has focused on the problem of anger vs. pity, and once he “solves” it with his supposed Aramaic reconstruction, he takes a victory lap on his trusty hobby-horse. But he has forgotten two other words in the pericope that indicate Jesus is not a happy Christos.

- ἐμβριμησάμενος (embrimēsamenos) — having snorted, having warned or rebuked

- ἐξέβαλεν (exebalen) — cast out, the same word Jesus used to get rid of demons

As Morna Hooker put it in The Gospel According to St. Mark:

We now have met three Greek words in this story (ὀργισθεὶς . . . ἐμβριμησάμενος . . . ἐξέβαλεν) which suggest agitation or strong emotion on Jesus’ part. (p. 81)

Now you see why I highlighted Bart Ehrman’s words above in bold: “He heals the man before rebuking him and throwing him out.” Jesus is angry. He sternly warns (or snorts at) the man. Then he kicks him out with a ferocity usually reserved for evil spirits.

Hooker, wrongly I think, concludes that Jesus is angry at the disease. But she rightly highlights the fact that all three of these words were so problematic that both Matthew and Luke eliminated the entire verse.

(A model for) change we can believe in

Casey’s explanation for why and how “anger” became “compassion” does not bear up under scrutiny. As we pointed out earlier Maurice is a first-rate Aramaic linguist, but as we’re finding out, a rather mediocre NT scholar and sub-par historian. Exactly why should a later copyist correct Mark’s bad translation of regaz? Ehrman was likewise perplexed when Bruce Metzger (in A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament) floated a similar idea:

It is possible that the reading of ὀργισθεὶς . . . arose from confusion between similar words in Aramaic (compare Syriac ethra’em, “he was enraged”). (Metzger, p. 65)

Concerning the phenomenon of “confusion in Aramaic,” Metzger cites p. 262 of Eberhard Nestle’s Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the Greek New Testament, which you can read on line at the Internet Archive.

But Ehrman rightly wonders what that buys us.

I have to say that arguments like this have always struck me as completely mystifying: I have never heard anyone explain how exactly they are supposed to work. Why, that is, would a Greek scribe proficient in Greek and copying a Greek text be confused by two words that look alike in Aramaic? We should not assume that Greek scribes spoke Aramaic (virtually none of them did), or that they copied Aramaic texts, or that they translated the Gospel from Aramaic to Greek. This Gospel was composed in Greek, transmitted in Greek, and copied by Greek and Greek-speaking scribes. So how does the accidental similarity of two Aramaic words relate to the issue? (p. 85, bold emphasis mine)

Metzger was actually arguing the opposite — that Mark originally wrote “with sympathy,” but some later copyist, confused by an Aramaic word that meant both, for some unknown reason wrote “with anger.” However, the problem remains in either case.

Let’s construct a series of events that conforms to Casey’s assertion.

- A written version of the pericope appears in Aramaic, shortly after the crucifixion.

- Mark writes his gospel (according to Maurice, decades earlier than most scholars think).

- Mark sees the word “regaz,” and because of interference, he writes orgistheis (with anger).

- Later, Matthew and Luke see orgistheis and remove it as they copy Mark.

- Much later, presumably after the Diatessaron, a copyist looked at orgistheis and wrote splanchnistheis instead. The reason? Because he somehow knew that Mark must have seen an Aramaic word that covers the same range of meaning as “with anger” and “with sympathy,” and he corrected the verse to conform to the Aramaic original.

The problem, as Ehrman clearly stated, is that no second-century Greek copyist would be fluent in Aramaic, let alone know how to reconstruct an Aramaic text from the Greek in front of him.

Here’s a simpler series of events.

- Mark writes his gospel, probably around 70 CE.

- In the story of the leper, he writes that Jesus was angry and means it.

- The text remains unchanged until the second century.

- As each year goes by, the picture of an angry Jesus makes less and less sense to Christians.

- Finally, at least one copyist encounters orgistheis in the text, thinks it must be a mistake, and changes it.

But why did he not simply remove the word, as Matthew and Luke did? Because he had just recently copied Matthew 20:34, which begins:

σπλαγχνισθεὶς δὲ ὁ Ἰησοῦς ἥψατο τῶν ὀμμάτων αὐτῶν . . .

Having been filled with compassion, he touched their eyes . . .

He remembers a similar healing scene in which Jesus heals two blind men by reaching out and touching them. Our scribe didn’t know Aramaic. He didn’t reconstruct an Aramaic source. He simply remembered the way “it ought to be,” and changed it accordingly, using a known model.

I suggest that this is a far simpler and more likely explanation of what happened. We should prefer a solution that requires fewer entities and whose pattern for change relies on a document that actually exists (viz., Matthew), instead of a hypothetical document written in a language the copyist would not have known.

Maurice Casey: Lumper

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the other reason Casey makes a big deal about the Aramaic origins of Mark’s gospel. He wants as early a date as possible for Mark so he can more convincingly argue that the evangelist had access to eyewitnesses and “wax tablets.”

Further, he knows that some mythicists argue for a late date (cf. Dorothy Murdock), and so lumps them together as if they are all of one (nefarious) mind. For example:

We have seen that one of the most extraordinary features of the mythicist position is the attempt to date all four canonical Gospels much too late. (p. 52)

Of course, if he knew anything about Doherty and Wells, he’d know that they date the Gospel of Mark well within the first century CE. Casey again:

This is why, as mythicists try to date the Gospels as late as possible, one of the reasons they use is the date of surviving manuscripts. In doing this, however, they show no understanding of the nature of ancient documents and their transmission, which was very different from the writing of books in the modern world. (p. 43)

Mo is taking advantage of the fact that his readers probably won’t check to see what any mythicist really wrote. The average layman is too busy to check Casey’s sources and doesn’t realize that some scholars strive to be accurate and honest only when it suits them.

At first, when I started reading this book I felt sorry for Dr. Casey and hoped not very many people would buy it, so as to spare him further embarrassment. But now that I see that the usual suspects on the web are praising it, I’ve changed my mind.

By all means, buy it. Read it. And then make fun of it. It deserves, loud, sustained, and public ridicule.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

1. If Jesus said something, then it would be in Aramaic.

2. This passage is in Aramaic

C. Therefore, Jesus said it

Quite so. May I be the first to call you “Doctor” Quinton.

I recall reading somewhere that Casey’s book wasn’t going discuss Paul’s silence regarding a historical Jesus and I thought to myself “Are you fucking kidding me?” How can anyone even address mythicism, much less refute it, without discussing Paul?

Actually, he does mention Paul, and in the process embarrasses himself by writing about high-context and low-context cultures.

Clearly, there is much trouble and distortion when scholars skim the dusk jackets of books and think they understand things.

Yes, a letter of *16* chapters length like 1 Corinthians , which reminds people that only one person can win a race, is an example of a ‘high-context’ culture, where important information does not need to be repeated.

Just think how long that letter would have been if Paul had been living in a low-context culture!

How can anybody write as though Paul had to keep the lengths of his letters down? Haven’t they even opened a Bible?

CASEY

The Aramaic regaz, however, means both ‘be angry’ and ‘be deeply moved’, which makes perfect sense.

CARR

So Casey is claiming that a miracle story must have happened, because it makes ‘perfect sense’ that Jesus would have been ‘deeply moved’ by the plight of somebody begging to be healed?

Is that it? Is that the ‘evidence’? Is that the smoking gun which makes the story historical?

Gosh, it makes ‘perfect sense’ that Harry Potter would have cried when he heard that Dumbledore had died.

And remember, this leap of illogic was based on Casey’s claim that he has psychic powers and can read Aramaic sources he has never seen better than bilingual people who have them in front of them!

This is despite the fact that Casey has never once in his life been able to produce an Aramaic reconstruction of a Greek document and had it checked against the original Aramaic document to see just how good his abilities of reconstruction really were….

You’ve said this before, but I don’t expect Casey and Steph ever to take you up on it.

Two issues here are worth pursuing.

1. Can we find any extant Greek translations of Aramaic texts wherein the translators make the same errors that Casey claims “interference” has caused in the gospels?

2. Given a Greek translation of an extant Aramaic text, can Casey, using his methodology and applying his matchless skills, reproduce the Vorlage?

These are empirical models that could decisively prove whether Mo is the real deal or a huckster.

I suppose the use of Persian loanwords in Daniel means that Daniel was a historical individual. With some cleverness, we might do the same for Jonah, Moses, even Enoch. In fact, Casey’s historical methodology could revive all kinds of mythical and literary characters.

Casey’s explanation for why and how “anger” became “compassion” does not bear up under scrutiny.

Maybe not, but experiencing a sense of compassion and feelings of anger, together, is not necessarily mutually exclusive.

I’m afraid you’ve missed the point. I have no argument with the idea that “experiencing a sense of compassion and feelings of anger, together, is not necessarily mutually exclusive.”

The question is how the word in Greek got changed as the manuscripts were copied. Some manuscripts of Mark say “with compassion,” while others read “with anger.” We start with the assumption that the original autograph of Mark contained one or the other. So which was it?

Most scholars today would probably argue that the original was “with anger,” and that some later scribe(s) softened the text to “with compassion.” They follow the principle that “The more difficult reading is the stronger.” It is a normal and observable process.

But what Casey argues is that the underlying Aramaic is the best explanation for the change in the Greek text. I don’t see how that’s possible, since a second-century scribe would not have had access to the supposed original Aramaic text and would almost certainly not have been bilingual, even if he had that text.

I will grant the possibility of an original Aramaic text that contained the word “regaz.” It’s also possible that Mark translated regaz into the Greek word for “with anger.” However, Casey’s theory for how the change from “anger” to “compassion” occurred is completely implausible.