After a couple or more years I’m finally completing the formatting of my notes from Philip R. Davies’ In Search of Ancient Israel, the book that is said to have sparked the public debate between “minimalists” and “maximalists”. The earlier chapters are outlined on my In Search of Ancient Israel web page.

The first section, The Exile, is a bit of a recap of an earlier section that was dealt with more fully in the web page above. I’m pushing myself to get this completed and sense that I have clung too closely to Davies’ words and outline in too many places and not taken the time to stand back and find the most appropriate ways of both framing and expressing the ideas so their essences can be grasped quickly. I also need to give more time to smoothing its connections to the earlier sections. Have decided to post it here as a draft and with a view to editing it after a time before adding it where it will belong as the next chapter on my webpage notes.

The point of this post may not be clear unless one knows a little of the background, which is to be found in the earlier chapters (see the vridar.info page). The basic theme it is addressing is that the conditions — economic, social, political, ethnic, linguistic, cultic, geopolitical, cultural and literary — were never to be found in Palestine right up to the time of the exile of the kingdom of Judah. Davies argues that the requisite conditions to produce the biblical literature — indeed, the idea of “biblical Israel” itself — did not exist until the time of the Persian empire. (Some other background posts on this theme are also kept in my Biblical archaeology archives.)

The Exile

We do not know if the Babylonians deported from Judah only the ruling classes and their servants or also some of the peasants.

Although we cannot estimate the numbers deported, “the reduction of population [from deportation, refugees, deaths] may have been as much as fifty percent immediately.” (Davies, 1995: p. 75)

Deportation was a long-established custom, made an instrument of imperial control by Assyrians (though not at all monopolized by them), and used, as well as to punish, deter and pacify, also to import much-needed labour into the Mesopotamian heartland. (p. 76)

The custom was to remove temple furniture, including images of the gods.

Official archives would have either been confiscated and taken to Babylon, or, more likely, have been left behind in Judah which still had to be administered.

What is fairly certain is that the Judaean deportees will have had no further access to these administrative documents, and it is not easy to imagine that they were allowed to take with them privately any other scrolls (assuming such literature existed), since the point of deportation is to alienate people from their homeland. (p. 76)

The deportees, as displaced peoples normally do, quite likely established themselves as ethnic communities in their new lands. We need not assume that they had to gather literary documents from their homeland to reconstitute their national identity.

Of the life of the deportees, of refugees or of those remaining in Judah we actually know virtually nothing. . . . [I]t is biblical scholarship which has painted an entirely fanciful portrait of religious fervour and furious literary creativity among Judaeans in Babylonia. (p. 77)

The Return

The Persian empire replaced the Babylonian and the area of the old kingdom of Judah became the province of Yehud. Yehud province was part of the satrap “Beyond the River” that extended from Babylon and the Euphrates River to Egypt.

Perhaps significantly, this is the one historical period in which the land promised to Abraham in Genesis 15:18 exists as a political unit. (p. 77)

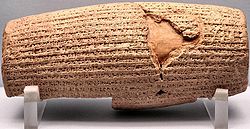

The Cyrus Cylinder informs us of Persian imperial policy in this period. There is an online translation and transliteration of its text, but a relevant portion says:

I returned the images of the gods, who had resided there [i.e., in Babylon], to their places and I let them dwell in eternal abodes. I gathered all their inhabitants and returned to them their dwellings. In addition, at the command of Marduk, the great lord, I settled in their habitations, in pleasing abodes, the gods of Sumer and Akkad, whom Nabonidus, to the anger of the lord of the gods, had brought into Babylon.

Archaeological evidence points to this policy affecting the province of Yehud. While surrounding areas show a drop in the number of settlements, Yehud itself shows a 25% increase.

These new settlements of Yehud are:

- nearly all small unwalled villages

- two-thirds built on sites that had not been inhabited during the kingdom of Judah

- 25% entirely new sites built on areas previously uninhabited

- dated to the end of the sixth century (the Persian period) by the pottery remains

It is hard not to associate these sites with a repopulation of Yehud under Cyrus and/or his successors . . . (p. 78)

This evidence in the ground indicates that the Persian rulers claimed the land of Judah/Yehud as an imperial domain and set about a planned policy to develop the agricultural potential of the area.

This implies that there would have been no land claims by either the immigrants nor the indigenous population, and thus no struggle between returnees and remainers over land holdings, as is so often assumed.

If so, then we cannot think in terms of a returning deportees rejoicing in the return to their original home towns.

Rather, we must think of another deportation, a transportation, coercion.

The area was being recolonized by Persia for economic and/or strategic purposes.

If so, the returnees were not necessarily Judaean ‘exiles’ or beneficiaries of some enlightened policy of undoing wrongs to earlier populations.

Perhaps the ancestors of these new immigrants did come from Judah, as the biblical literature insists, but that should not be assumed. Perhaps they came from all parts of Palestine, or perhaps even from elsewhere. The claim made by the biblical literature that these people are returning exiles is powerfully made, and is all but universally accepted. Yet it is not pig-headed scepticism that hesitates, but rather reflection and common sense. (p. 78)

Davies continues:

For whether originally from Judah or not, these people or their descendants would be likely to believe, or to claim, that they were indigenous. Indeed, the Persians may well have tried, in order to facilitate compliance with the process, to persuade these transportees that they were being resettled in their ‘homeland’, and examples of this ploy in the imperial history of humankind could be cited. In fact . . . some biblical stories (e.g. the Abraham stories, the Joshua conquest stories) may indicate doubt among some inhabitants of Yehud that they did inhabit the land as erstwhile natives. In short, the biblical claim of repatriation cannot be accepted without some reserve, and pending some confirmation from non-biblical sources we are better to adopt a neutral stance on the matter. (pp. 78-79)

Thomas L. Thompson points to interesting comparisons between the Babylonians and Persians in this respect. (This is my own addition here — Thompson’s work was published after that of Davies.) When each empire attained a position of unchallenged supremacy, it no longer needed to maintain policies of brutal suppression, but could afford the luxury of rebuilding infrastructures of subject populations without risk of losing control.

In this context, the propagandistic function of deportation texts take on a more persuasive character. Simply put, the Babylonian and Persian administrations had the luxury of presenting themselves as the liberators and benefactors of their subject peoples, and were able to cast their predecessors (the Assyrians, and the Babylonians in their turn) as barbaric oppressors of the people. This genre of propaganda is transparent. (Thompson, 2000: p. 416)

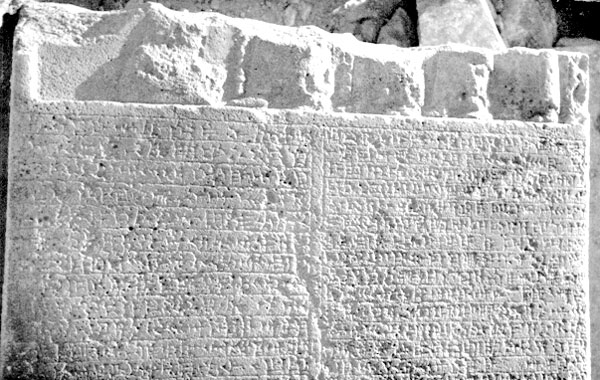

Thompson proceeds to discuss an earlier Babylonian equivalents of the Cyrus Cylinder, two stelae of Nabonidus and his mother.

In these inscriptions Babylonian royalty boasts of “restoration” of the “original” gods at the city of Harran. They list nations – Babylon, Syria, Egypt — from which the royal family brought peoples to serve these gods and repopulate the city. The gods’ return was understood to be the people’s liberation and restoration, too.

This theme of the emperor as the “restorer” of the gods and of the “indigenous” populace is found throughout the Babylonian deportation inscriptions. Conversely in these texts, the destruction of the cults and temples of the subject peoples is blamed either on the Assyrians or on barbaric allies. The Babylonians take the high ground as champions of the oppressed population, acting under Marduk’s instruction, restoring cities and their populations, rebuilding the temples and dedicating deportees as temple servants of the gods.

The ideological thrust of deportation policy was perfected by the Persians. [The imperial propaganda machine declared that Cyrus] didn’t need weapons for this conquest. The people greeted him with open arms, tears of joy and song. Rather than murder and pillage, Cyrus tirelessly restored both gods and peoples to their homes. This transportation of gods and populations under the title of “restoration” is indeed declared by the scribe as the primary function of empire, a literary policy which is continued under both Xerxes and Darius II. (Thompson, p. 417)

So it looks as though what we have traditionally considered a unique cultural-religious event – the “restoration” of the “Jews” to “their land” by the Persians – was in fact just one more of many ancient deportations dressed up in the propaganda of liberation.

Back to Davies’ work . . . .

Organization of the Persian Yehud

Tribalization

Weinberg (1973) “has argued that one uniquely Persian innovation was the bêt ʼabôt (House of the Fathers), which involved a “deliberate reconstitution of social groupings, a “tribalization” which, like all tribalizations . . . is not ethnic nor primary, but economic and secondary.” (Davies, p. 79)

This was probably part and parcel of the initial stage of Persian reconstitution of Yehud, its economic and agricultural development, in the time of Cyrus or more probably Darius (from the end of the 6th century).

Militarization

In the mid-fifth century (under Xerxes) a chain of fortresses sprang up along the trade routes from the Mediterranean to the Jordan and down to the Negev, including Arad and Beersheba. These were garrisoned by Persian military, presumably in response to the growing challenge from Greece along the Mediterranean and nearby trade routes. This “militarization” may have had significance for the mission of Nehemiah.

Citizen-Temple-Community?

Persians took care to rebuild local cult centres, according to archaeological evidence from Babylon and Egypt.

A social model with a name coined by Soviet scholars, Burger-Tempel-Gemeinde (Citizen-Temple-Community), has been used to explain how the temple functioned as an economic and political hub of society, particularly in reference to slightly later Asia Minor temple societies. But it appears to have many features that apply to Yehud in this Persian era, too.

It is only a model and can only be used to infer what society might have been like in Yehud.

Temple personnel and land owners unite to form an autonomous economic and social unit. This appears to be an adaption of the Mesopotamian temple system where the temple:

- owned and administered much of the land (owned by the god),

- acted as the city’s treasury,

- and whose priests often acted as civic rulers.

A key element of this Burger-Tempel-Gemeinde model is that it posits a privileged group (the temple personnel and land owners) within a larger society. Compare the theme of the Book of Nehemiah in which a newly arrived population keeps itself apart from the local inhabitants and thinks of them as ethnically and cultically impure. This elite group maintained control of the Temple and economy.

Or Palestinian Parties?

An alternative model to the Burger-Tempel-Gemeinde one above is one proposed by Morton Smith. He proposes the return of two distinct groups, a “Yahweh-alone” party, and descendants of the former Jerusalem priesthood. Both groups were in opposition to the indigenous inhabitants of the land. Nehemiah was a tyrant (in the technical or ancient Greek sense) who won control of the Temple (and the society) for the Yahweh-alone party.

An Egyptian Ezra

The chronology and even the existence of the biblical Ezra are matters of debate. But we do know of an Egyptian priest, Udjahorresnet, sent back to Egypt by the Persian monarch Darius I “to reorganize the priestly ‘houses of life’, i.e. the scribal schools. This may well have included responsibility for reorganizing the cult.

We also know “that Darius had the traditional Egyptian law codified and written up in Aramaic and Demotic Egyptian.” (p. 82)

The career and acts of Ezra consist of a remarkable parallel.

The above sequence of development – from economic and tribal organization, to militarization, to the establishment of a temple cult and law and constitution – may be thought to correspond to the sequence of events in the narratives of Ezra and Nehemiah.

The Birth of Biblical Israel

The above description of the organization of the Persian province of Yehud describes the earliest appearance of the sort of society that we could expect to produce the concepts associated with the biblical Israel.

For the first time in the history of Palestine we see the evidence for:

- the creation of a society brought into Palestine from outside; an exclusive exile society

- the organization of a society on what it sees as a traditional cult around a temple; a central sanctuary and law

- the same society’s identification as a new ethnic entity; ethnic “tribal” collectives

But a more detailed explanation for the origin of the biblical literature will be in a future post.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I do agree that tribes may be artificially constituted rather than naturally arising. They are added to for political reasons by tyrants or reformers. We know this happened in ancient Athens (see e.g. http://www.stoa.org/athens/essays/tribes.html ) and according to some stories in ancient Rome.

Good point. The tribes of Athens (of military and economic origins) make an interesting backdrop highlighting the nature of some ancient societies.

Sir,

Your Posts are well Researched and supported by proper Links.

Being from India, I Use them in my blogs without any Modifications and also try to mention your source also, unless I miss it.

Continue your Good Work.

Alexander Fantalkin argues that the militarization of Achaemenid Palestine took place in the fourth, not mid-fifth, century BC and was a result of the rebellion of Egypt.

I would like to catch up with the more recent archaeological evidence on this period, including Fantalkin. Unfortunately, it appears that in many cases archaeologists of Palestine have rushed through the top layers of evidence (where “only” Persian or Hellenistic era artefacts have been found) to get to the “real history” of “Biblical Israel”. The tragedy may be that the real history actually existed in those Persian and Hellenistic eras and what predated that was something quite unrelated to popular myths and ideologies.