My previous post discussed John Ashton’s observation that the Prologue of the Gospel of John owes something to the ancient noncanonical Jewish beliefs about Wisdom as expressed in Ecclesiasticus or The Wisdom of Ben Sira. This post is intended to be read as a part of that post.

Without wanting to misrepresent the central themes of John Ashton’s book, Understanding the Fourth Gospel (2nd ed) — it is NOT about the noncanonical sources of the Gospel of John as I might appear to be suggesting here — there is the other side of the message of the Prologue that Ashton also addresses, and that is the return of the Logos from earth back to heaven.

Without wanting to misrepresent the central themes of John Ashton’s book, Understanding the Fourth Gospel (2nd ed) — it is NOT about the noncanonical sources of the Gospel of John as I might appear to be suggesting here — there is the other side of the message of the Prologue that Ashton also addresses, and that is the return of the Logos from earth back to heaven.

The Prologue concludes with Jesus returning to the bosom of the Father in heaven:

No one has seen God at any time. The only begotten [. . . varying MSS lines for God or Son . . .] who is in the bosom of the Father, he has declared him. (John 1:18)

As Ashton remarks, with the return of the Son of God to the Father at the end of the Prologue, the story is in effect over before it begins.

But the theme of Jesus returning to the Father is picked up again later in the Gospel. Jesus’ death is depicted by the evangelist as an ascent to heaven, a return to the Father who sent him, an ascent back to his original home in heaven with the Father:

Then Jesus said to them again, “I am going away . . . Where I go you cannot come” . . . Then Jesus said to them, “When you lift up the Son of Man, then you will know . . .” (John 8:21, 28)

“And I, if I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all . . . to myself” (John 12:32)

“I am going to the Father“ (John 14:12, 28)

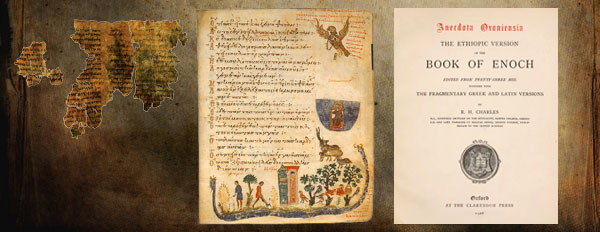

If the Wisdom of Ben Sira expresses a Jewish belief that “Wisdom” was sent into the world but was rejected by the world, with the result that only a chosen few (Israel) received Wisdom as their own where she could dwell (until rejection and failure to recognize her set in), another noncanonical Jewish book, 1 Enoch, completes this thought by declaring that after Wisdom had been sent she returned to her place in heaven.

Wisdom found no place where she could dwell, and her dwelling was in heaven. Wisdom went out in order to dwell among the sons of men, but did not find a dwelling; wisdom returned to her place and took her seat in the midst of angels. (1 Enoch 42:1-2)

This is the conclusion of the Prologue and it is also the conclusion of the Gospel of John. (The resurrection and epilogue are clumsily added end-tags that add nothing to the message and meaning of the Gospel.)

Jesus, after having been sent by the Father from heaven with a revelation from God — a revelation that is expressed in the Gospel narrative’s Works, not Words, since the words themselves “reveal” nothing more than that Jesus was the revealer (Ashton building on Bultmann) — returns to his home in heaven and to the Father who sent him.

Thus Jesus, like Wisdom as attested in noncanonical Jewish scriptures, is sent from heaven, descends therefore from heaven, is rejected on earth, finds a dwelling place among a few, then ascends back to heaven.

As Ashton remarks, (from memory) if this is not gnosticism, it is (nonetheless awfully) close.

This notion of descending from heaven and ascending back to heaven is also a Son of Man motif in the Gospel. This is established from the beginning when Jesus tells Jesus that Nathaniel will see the angels ascending and descending upon the Son of Man (1:51).

The descending and ascending motif is also a noncanonical Wisdom motif. If (as is argued elsewhere and by others) the Son of Man is associated with the cult of royalty, kings, in Israel (compare the development of the notion of “Son of Man” from the original Aramaic text in Daniel where a kingdom of Israel is to replace the kingdoms of gentiles represented by beasts), then it appears that the Gospel of John represents an attempt to merge this royal Son of Man with the idea of the Logos, the true Wisdom that is replacing the Law of Moses (1:17), descending and ascending in relation to its home in heaven.

We thus see here in the Gospel of John how a death of the heavenly messenger, the Christ even (though this title is not overly emphasized, apparently, in the original strata of the Gospel of John) is seen as a positive event in its own right, and requires no resurrection sequel to touch it up with extraneous “hope”. In the Gospel of John the death of Christ is equated as a glorification of Jesus, an ascent to heaven, a return to the Father.

In addition to the above passages cited from GJohn, we have:

And Jesus answered them, saying, The hour is come, that the Son of man should be glorified. Verily, verily, I say unto you, Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit. (John 12:23-24)

Therefore, when he was gone out, Jesus said, Now is the Son of man glorified . . . (John 13:31 in context of Judas going out to betray Jesus and initiate the events leading to his death)

These words spake Jesus, and lifted up his eyes to heaven, and said, Father, the hour is come; glorify thy Son, . . . .

And now, O Father, glorify thou me with thine own self with the glory which I had with thee before the world was. (John 17:1, 5)

For the Johannine school of Christianity, the death of Jesus was in and of itself a glorious thing — it was Jesus’ return to heaven and the Father. His being “lifted up” by crucifixion was paradoxically actually a “lifting up” back to heaven!

One can begin to see how the gospel’s inclusion and rewriting of resurrection appearances of Jesus can be argued as superfluous. There are several reasons for thinking that they were never part of the original text quite apart from the above. Examples: angels appear to deliver one-liners without waiting for answers; the appearance of Jesus to the disciples fearfully locking themselves in a room knows nothing of the next scene where we learn that Thomas was missing; etc. Indeed, as Gregory Riley argues in Resurrection Reconsidered, someone was using the Gospel of John’s turf to argue against other Christians who followed Mary, Peter and Thomas as their lead-disciples.

One conclusion:

John Ashton’s Understanding the Fourth Gospel is not about noncanonical sources of the gospel. But he does offer enough evidence to remind us that understanding Christian origins requires a broader outlook than seeking to relate everything in the New Testament gospels back to something in the canonical Jewish literature, or Old Testament.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!