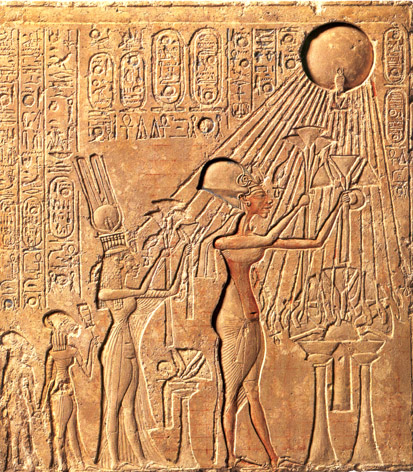

Akhenaten refresher

- Egyptian Pharaoh who ruled for 17 years in middle of fourteenth century, up till around 1336 or 1334 BCE

- originally known as Amenthotep IV (or in Greek, Amenophis IV); changed his name to Akhenaten

- opposed the orthodox priests of Ammon-Re; redirected their income to his new god Aton

- abolished traditional cults and idols of Egyptian polytheism

- established the sole worship of a new god of light, Aton, (variously described as monotheism, monolatrism and henotheism)

- depicted Aton as sun disc with rays ending in hands, understood to be a universal god incapable of true representation

- established new centre of worship at Akhetaten (today known as Amarna)

- temples to Aten stressed worship in open sunlight (contrary to earlier custom of darkened indoor temples)

- Akhenaten was the sole mediator between Aton and earth

- affinities between Hymn to Aton and Psalm 104

- son was the famous Tutankhamen

Unlike Moses, Akhenaten, Pharaoh Amenophis IV, was a figure exclusively of history and not of memory. Shortly after his death, his name was erased from the king-lists, his monuments were dismantled, his inscriptions and representations were destroyed, and almost every trace of his existence was obliterated. For centuries no one knew of his extraordinary revolution. Until his rediscovery in the nineteenth century, there was virtually no memory of Akhenaten.

Moses represents the reverse case. No traces have ever been found of his historical existence. He grew and developed only as a figure of memory, absorbing and embodying all traditions that pertained to legislation, liberation, and monotheism. (Assmann, Moses the Egyptian, p. 23)

This current series of posts has arisen out of Professor Chris Keith’s references to Egyptologist Jan Assmann’s comments about social memory theory in history. Keith uses memory theory to “answer questions about the historical Jesus”. By starting with the gospel narratives as memories of Jesus that have been necessarily reinterpreted he attempts to uncover those narrative details that most likely point to a past reality about Jesus. In Jesus’ Literacy, for example, he judges the Gospel of Mark’s implication that Jesus was was not scribally literate to be more likely a memory reflection of the real historical Jesus than the Gospel of Luke’s suggestion that Jesus was able to competently read the Jewish Scriptures.

However, when I read the first two chapters of Assmann’s Moses the Egyptian I read an approach to social memory that is the opposite of the one used by Chris Keith. Keith begins with the Gospels that are assumed to record certain memory-impressions and attempts to work backwards to what those original events more or less looked like to observers. But as I wrote in my earlier post that’s not how the Egyptologist works:

The Egyptologist begins with “hard evidence” and originally genuine historical memories and works his way forward into the later literature to find out what must have become of these memories. The historical Jesus scholar, it appears to me, begins with the later literature and tries to guess what memories came before it.

The two methods look to me to be like polar opposites rather than “similar”.

It is a pity Chris Keith is too busy to engage with Vridar (no reason given in his personal email, just a copy of a cordial invitation to respond to a Nigerian banker-benefactor asking me for my account details) at the cost of public religious literacy. I would love to discuss these questions with him seriously but he’s clearly not interested. (Slightly revised)

The difference is potentially very significant. Take the different versions of the Moses-Exodus narratives that we have seen in the recent posts — each one a differently interpreted memory — and apply Keith’s method to those in order to arrive at information about “the historical Moses” and the “historical Exodus” and see what happens. As we saw in that first post Assmann has doubts that there even was a historical Moses in the first place and he does not believe there ever was a biblical-like Exodus led by such a figure. Applying Keith’s method to “answer questions about the historical Jesus” to these memory-narratives would produce a very false notion of Egyptian and Jewish history.

Assmann starts with something we lack in the case of the historical Jesus. The known events of Egyptian history according to the contemporary inscriptions. These are used to interpret the later “memory literature”. The “memory literature” is not used in an attempt to uncover past historical events. The past historical events are used to interpret the subsequent stories.

Keith may object that he does use what is known of the historical past in order to assess what is closest to historical reality in the Gospels. He does, for example, in Jesus’ Literacy delve into what we can know about the nature and extent of literacy in ancient Palestine. But this tells us nothing new or relevant to the actual historical Jesus. It is comparable to uncovering details about the historical Pilate, or the architecture of the Jerusalem Temple, or the geography of Galilee. No-one would believe we are coming any closer to “the historical Moses” by learning all we can about the Egyptian religious customs and beliefs, the social structures, ethnic groups or literacy in ancient Egypt and Palestine and applying this knowledge to any of the stories we have about Moses.

So here’s how Assmann uses social memory.

.

Begin with the known historical facts

- Seventeenth century B.C.E., “the Hyksos, a population of Palestinian invaders, settled in the eastern delta and went out to rule Egypt for more than a hundred years.” (p.24)

- There was no religious conflict between the Hyksos and the Egyptians. “The Hyksos were neither monotheists nor iconoclasts. On the contrary, their remaining monuments show them in conformity with the religious obligations of traditional Egyptian pharaohs, whose role they assumed in the same way as did later foreign rulers of Egypt such as the Persians, the Macedonians, and the Romans. They adhered to the cult of Baal, who was a familiar figure for the Egyptians, and they did not try to convert the Egyptians to the cult of their god. The whole concept of conversion seems absurd in the context of polytheistic religions.” (p.24)

I quote here from one of Assmann’s sources, an article by fellow Egyptologist, Donald B. Redford, “The Hyksos Invasion in History and Tradition” (Orentalia, Vol. 39, No. 1, 1970)

In Egyptian texts emanating from the close of the Hyksos occupation and shortly thereafter no conscious effort is evident to propagandize by vilifying the invaders. They were vile Asiatics who had wrongfully seized Egypt; that was enough to justify any resistance or liberation movement. (p.31)

Redford informs us that the first indications that the Hyksos were associated with religious aberrance was in the fifteenth century under Hatshepsut who declared that the Hyksos rule had eschewed by the god Re (p.33).

- Fourteenth century B.C.E., the first conflict in recorded history between two opposing religions took place in Egypt. “In its radical rejection of tradition and its violent intolerance, the monotheistic revolution of Akhenaten exhibited all the characteristic features of a counter-religion. Within the first six years of his reign, Pharaoh Amenophis IV changed the whole cultural system of Egypt with a revolution from above in a more radical way than it ever was changed by mere historical evolution.” (p. 25; see the “Akhenaten refresher” above for details)

Assmann describes that conflict in stark terms:

The monothestic revolution of Akhenaten was not only the first but also the most radical and violent eruption of a counter-revolution in the history of humankind.

- The temples were closed,

- the images of the gods were destroyed,

- their names were erased,

- and their cults were discontinued.

Assmann stresses what must have been a traumatic experience for many Egyptians. Rituals were believed to be linked to cosmic and social order and to bring them to an overnight halt was surely a “terrible shock” to many. Putting an end to the festivals (when the gods came out from their temples to appear in processions to the public) was a blow against the social identities of people who associated themselves closely with their local deities.

- Hard on the heels of this “catastrophe” came a plague which “swept over the entire Near East — probably including Egypt — and raged for twenty years. It was the worst epidemic which this region knew in antiquity.”

It is more than probable that this experience, together with that of the religious revolution, formed the trauma that gave rise to the phantasm of the religious enemy. (p. 25)

(The contemporary evidence for this plague is set out in Redford’s article, page 45.)

- The historical memory of the religious revolution was erased by those who replaced Akhenaten’s dynasty.

The recollection of the Amarna experience was made even more problematic by the process of systematic suppression whereby all the visible traces of the period were deleted and the names of the kings were removed from all official records. The monuments were dismantled and concealed in new buildings. Akhenaten did not even survive as a heretic in the memory of the Egyptians. His name and his teaching fell into oblivion. (p.27)

In summary:

- Hyksos were Asiatic rulers of Egypt, detested by Egyptians but not for religious reasons

- Egyptians eventually expelled them

- Religious unorthodoxy was later associated with the Hyksos

- A counter-religion revolution took place in Egypt; old gods and cults were destroyed; a single god, without images, replaced them

- Plague accompanied or soon followed this revolution

- Memory of this religious revolution was erased and not rediscovered till the nineteenth century.

Drawing conclusions from the above facts

We have every reason to imagine the Amarna experience as traumatic and the memories of Amarna among the contemporary generation as painful and problematic. . . . Only the imprint of the shock remained: the vague remembrance of something religiously unclean, hateful, and disastrous in the extreme. . . .

Since every trace of the Amarna period had been eradicated, there was never any tradition or recollection of this event and its cultural expression until the nineteenth century, when the archaeological traces of this period were discovered and interpreted by modern Egyptology. The memories of this period survived only in the form of trauma. The first symptoms of this may have become visible as early as some forty years after the return to tradition, when concepts of religious otherness came to be fixed on the Asiatics, who were Egypt’s traditional enemies. In this context, the dislocated Amarna reminiscences began to be projected onto the Hyksos and their god Baal, who was equated with the Egyptian god Seth. (p.28)

Assmann is saying that the myth of the religiously vile Asiatic could well have arisen as early as a generation or “some forty years” after the overthrow of the Akhenaten revolution. A void was created with the suppression of all memory of that period; and voids are readily filled by other “memories” as they arise.

Presumably by this time, other memories and experiences had invaded the void in the collective memory which had been created both by trauma and by the annihilation of historical traces. The Hyksos conflict was thus turned into a religious conflict.

(I should add here that Assmann includes a discussion of the nature of ancient polytheism and why it did not normally lend itself to religious conflict. The various gods of one people or locality were on the whole identifiable with those of another or easily translatable between cultures.)

Now we’re beginning to see how all of this relates to the various Moses-Exodus narratives we have seen in the recent posts.

.

Lepers and Jews; Moses as Akhenaten

In one of his most brilliant pieces of historical reconstruction, Eduard Meyer was able to show as early as 1904 that some reminiscences of Akhenaten had indeed survived in Egyptian oral tradition and had surfaced again after almost a thousand years of latency. [Eduard Meyer, Aegyptische Chronologie, Abhandlungen der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1904), 92-95.]

He demonstrated that a rather fantastic story about lepers and Jews preserved in Manetho’s Aigyptiaka could refer only to Akhenaten and his monotheistic revolution. (p. 29, my bolding and formatting in all quotations)

Assmann then refers to articles by Rolf Krauss and Donald Redford (cited above) substantiating Meyer’s thesis with additional evidence. Another scholar, Raymond Weill, rejected Meyer’s explanation as being “too monocausal”. Assmann’s view is that both Meyer and Weill were correct.

The story as told by Manetho and others integrated many different historical experiences, among them the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt in the sixteenth century B.C.E. But the core of the story is a purely religious confrontation, and there is only one episode in Egyptian history that corresponds to these characteristics: the Amarna period.

This axial motif of religious confrontation became conflated with the motif of foreign invasion.

The Amarna experience retrospectively shaped the memories of the Hyksos occupation, and it also determined the way in which later encounters with foreign invaders were experienced and remembered.

This explanation takes full account of Weill’s criticism without giving up Meyer’s important insight. The significance of this discovery for the project of mnemohistory is immense. Not only does it prove how trauma can serve as a “stabilizer of memory” across a millennium, but it also shows the dangers of cultural suppression and traumatic distortion. The Egyptian phantasm of the religious enemy first became associated with the Asiatics in general and then with the Jews in particular. It anticipated many traits of Western anti-Semitism that can now be traced back to an original impulse. This impulse had nothing to do with the Jews but very much to do with the experience of a counter-religion and of a plague. (p. 30)

It’s an interesting theory. It makes sense. At least to me.

In this light let’s look again at those different versions of the Moses/Exodus tale and note the tie-ins with the known history of Egypt:

Hecataeus

- begins with a plague in Egypt

- solution of the gods is to restore traditional worship and expel the foreigners who introduced alien worship

- some fled to Greece, others to Judea under Moses

- Moses introduced the worship of God without images and customs different from all other peoples

Lysimachus

- Leprous Jews fled to temples to collect food leading to shortage in Egypt

- God Ammon’s solution was to expel the impious from the temples into the desert and drown the leprous Jews

- Moses their leader was hostile to all other races and destroyed temples in land he conquered

Chaeremon

- God complained of temple desecration

- Restoration possible only by expelling the impure from the land

- Moses became their leader and joined forces with others who had been forbidden to leave; the combined to invade Egypt

- Egyptian king eventually drove the Jews back to Syria

Manetho

- Hyksos conquered Egypt, treated population cruelly, ruled 500 years

- Thumosis, king of Thebes, rebelled and besieged their city Avaris

- Hyksos subsequently emigrated to Syria, finally settled in Judea

Pseudo-Manetho

- King wanted to see the gods who had remained invisible

- To do so he had to expel the lepers to quarries and set apart city of Avaris for them

- Osarsiph became their leader; he introduced anti-Egyptian laws and worship

- Joined forces with Hyksos and ruled with terror over Egypt 13 years

- Hyksos and lepers were finally expelled from Egypt

Pompeius Trogus

- Egypt was plagued by leprosy; Moses was a prominent Egyptian

- Gods said that the cure was to expel Moses with those diseased

- Moses stole sacred objects, Egyptians attempting to recover them were turned back by storms

- Moses established laws to keep Jews separate from others

Artapanus

- Moses was Hermes and teacher of Orpheus

- Jealous Chenephres sought to kill him

- God appeared in a fire to order Moses to march against king Chenephres and rescue the Jews

- Moses returned but was imprisoned, escaped by divine miracle

- Plagues afflict Egypt, king relents, Jews escape to wilderness, Egyptians slain by fire and flood

Tacitus

- Plague in Egypt was causing bodily disfigurement

- God Ammon told king to remove the Jews, hateful to the gods, to another land

- Moses became their leader, found them water by following asses

- After 6 days they reached the land and expelled the inhabitants

- Set up worship that included ass idol, introduced customs opposed to all other races

Apion

- Moses was an Egyptian priest at Heliopolis

- Moses built temples and instituted worship practices different from Egyptian ones

Strabo

- Moses, an Egyptian, dissatisfied with his country’s worship, exiled himself

- He established worship without images

- The legalisms of contemporary Jews were introduced only after Moses’ death

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

there ‘s no need to discuss nuttin mit noone.

Some people just don’t get it and c. keith is just one more…..[apologist.]

My conclusion? Judeo-Christian studies belong in the folklore department; Egyptian studies belong in the ancient history department. The latter is based on real artifacts and contemporary texts; the former is based on “memory theory” and pseudo-historical texts.

The first main point here at least, seems surprisingly strong: Akhenaton was not known to us by much memory. But came to be known in our time primarily through archeology. Not sure about what follows from that, however.

I like Neil’s main methodological point. But am hesitant about many of Assmann’s conclusions.

I think the subtitle of a recent book by Tom Thatcher is telling — Why John Wrote a Gospel: Jesus–Memory–History. It shows how the Memory Mavens view the study of history differently from the old form critics.

Bultmann et al. started with the text in hand, attempted to identify the forms, uncover the oldest traditions, and reveal the oldest and perhaps authentic material embedded therein. On the other hand, MMs begin with a plausible, presumed Jesus, and then try to construct explanations for “how the New Testament got like that.”

Obviously, I’m not at all convinced that social memory theory is the proper tool for this ill-fated exercise. But beyond that, it seems wrong-headed to think that you can use the NT to invent a plausible Jesus and then use that same evidence to explain how the NT came to be. No matter how you wrap it up with opaque language and dubious references to “memory,” in the end they’re using the text as its own proof text.

Likely the Ackenaten evidence is solid. Though what Greeks later did with such material seems disputed here, seems like have some hard archaeology facts under it all.

As to the nexus, in any case, we note anthropology suggests this is typical. Many cultires have purity and semi medical purification rites. They are typically used to detoxify and mark members, initiates of one tribe – as apart from and superior to all others. So here Assmann seems partially if not completely verified.

In effect, the flight or expulsion of the Jews was an Egyptian purification ritual act.

If we follow the approach of Assmann, Redford and Meyer then here’s how we would go:

What material evidence do we have in past events that appear to correlate with the gospel narratives? We will find none, I think, in any world external to literature. We will see echoes of the gospels in the texts of the Jewish Scriptures and related Second Temple works. We will see in the gospels a post 70 context, with the events of 70 playing a significant role. The later gospel (John) also appears to relate strongly to the 70 context in its studied denial of the significance of that event.

These are the artefacts with which we assess the gospels. They are all literary/theological artefacts set against a post 70 context.

That’s where our explanation of the gospels and the narratives they contain must begin.

If we are looking at the larger question of Christian origins then we should also compare the gospels with the writings of Paul (on the tentative assumption that the epistles preceded the gospels).

This is dealing with evidence and attempting to explain evidence.

We should also test the mores speculative hypotheses such as those involving oral tradition. That is, rather than assume oral tradition(s) these should be tested: do the gospels really look like what we should expect from documenting or elaborating upon oral traditions or do other factors account more simply for the data in the gospels?

But more importantly, we should pin down “oral traditions of what, exactly?” How do we identify any particular oral tradition that found its way into the gospels without a circular argument?

I am reading Crossley’s “Jesus and the Chaos of History” at the moment. It’s a truly remarkable piece of scholarship. He presents all the evidence we have for eschatological expectations and not one bit of the evidence is found in the early first century but though smoke and mirrors he somehow concludes that it all proves that the early first century was awash with eschatological expectations. I may post about it one day, or maybe not. It’s too depressing to go over this sham scholarship.

Neil: It’s too depressing to go over this sham scholarship.

If not you, then who?

I would say you Tim!

Assmann’s approach is sound methodologically, but that does not guarantee good results. His conclusions are only as good as his evidence, and there are two unspoken assumptions regarding his evidence which are: (1) the evidence is what it purports to be; and (2) the various memories captured in the documents are independent of each other and not derivative, i.e., there is an implication of a gestalt or zeitgeist at play here.

For reasons I will not express here (and only some of which I have expressed earlier in this string of posts), I am confident that I can demonstrate the evidence is not what it purports to be, that it all dates to no earlier than the middle of the second century BCE, and that it either was the direct product of or subject to interpolations of anti-Judean polemics and counter-polemics. A smear campaign against the Hasmoneans cannot inform us about a suppressed Egyptian memory from over one thousand years before.

This has been a great series of posts and comments that has been very helpful to me in crystalizing the arguments I am about to make as well as in shoring up the evidence in support of those arguments, which further advance my overall thesis. Thanks.

P.S. Bee, I think your concern about Assmann’s conclusions could arise from the implied circularity his argumentation. He could not have found a suppressed memory from the evidence but for the fact that he knew of a memory that had actually been suppressed and appears to have gone looking for it. While his circle may not be the hermeneutic circle of most biblical scholars, it is still a circle. Still, if you recast Assmann’s conclusions as a hypothesis, which I believe is fair, his hypothesis appears to be falsifiable and, therefore, scientific.

The strength of Assmann’s (cum Meyer at al) hypyothesis is its explanatory power. It offers an explanation of the constellation of plague and exodus and counter-religion motifs.

(It does not attempt to inform us about otherwise suppressed historical events; it can’t do that. On the contrary, the “(long lost) historical events” offer information about the narratives.)

Another hypothesis can be tested the same way. What motifs would we expect to find given x, y, z?

“The strength of Assmann’s (cum Meyer at al) hypyothesis is its explanatory power.”

I am not sure what you are trying to say here. Assmann’s hypothesis explains nothing, if his assumptions regarding the evidence are wrong. Garbage in, garbage out.

“(It does not attempt to inform us about otherwise suppressed historical events; it can’t do that. On the contrary, the “(long lost) historical events” offer information about the narratives.)”

If the narratives were motivated by 2nd century BCE politics regarding the Hasmoneans, the (long lost) historical events (actually political rhetoric having no historical value) offer no information about the narratives. Assmann’s hypothesis rests primarily on the “earliest” narratives from “Manetho” being true and correct and dating to the early 3rd century BCE.

“Another hypothesis can be tested the same way. What motifs would we expect to find given x, y, z?”

I agree with that statement, which emphasizes the strength of the methodology over the strength of Assmann’s conclusions/hypothesis from applying the methodology.

Maybe we are in “violent agreement,” as they say at Intel.

I don’t know what it is that you think has not been given an explanation. I’m not sure we are focusing on the same question. I can understand one not agreeing with the explanation but I don’t understand how one can say nothing has been explained at all. You say you are not sure what I’m trying to say so I think we are looking at quite different questions and getting our wires crossed.

But A’s thesis does not “rest primarily” on Manetho by any means. You can leave Manetho out altogether. Ignore it– whether Manetho interpolations, pseudo-Manetho or whatever. To suggest the theory itself rests primarily on Manetho has A’s argument back-to-front, at least as I understand it and have tried to explain it.

Perhaps we are talking past each other — each looking at a different question. I don’t understand you any more than you say you don’t understand me.

We are talking past each other.

I’ve gone back and reread the relevant portions of Assmann, and the two passages from Manetho are indeed central to Assmann’s and Meyer’s thesis as the inclusion of two different stories of Jewish origins is what provides the basis for arguing the existence of a “motif.”

Am I saying that there is nothing in these passages that is not genuinely Manetho? No. There may be things in those passages that are genuine Manetho, but I am confident (for reasons I will explain later elsewhere) that Manetho did not, could not and would not have had any reason to equate the Judeans (the Greek word for “Jews”) or Jerusalem with the Hyksos or “lepers” expelled at the close of the time of Ahkenaten.

The worst part of this is the fact that Assmann knew or should have known about the controversy regarding the two “Manetho” passages upon which he relies:

“Several scholars have attempted to analyze the citations in Josephus, attributing some portions to pro-Jewish publicists, others to anti-Jewish writers, others to a Greek whose interest was academic rather than polemical—and even some sections to Manetho. But the different scholars have offered different allocations, and none has proven authoritative. The problem of seeing genuine Manetho in these fragments has been called the most difficult problem in Classics, and so it remains.

The student must not, therefore, be quick to accept the anti-Jewish material (such as in FI2 §§232-51) as Manetho’s writing. Similar material (the unclean lepers and misfits) is found in other writers, such as Lysimakhos of Alexandria,54 and it may have been injected into Manetho from outside. Manetho, writing his History of Egypt in the early third century B.C., was perhaps too early for the rising wave of polemic. He may or may not have mentioned the Jews and the Exodus; and, if he did, we cannot be certain as to his point of view.

Besides being embellished, altered, and excerpted, Manetho’s work was also converted—probably from the altered version—into a condensed version, an epitome, in at least one edition. Again, we cannot say when the epitomizing was done or who did it. The results can be seen in F2a: the narrative was almost entirely cut out, leaving the succession of dynasties with the names of the rulers and the lengths of their reigns—an outline very similar to what Manetho may have begun with.”

Assmann could not be bothered to admit that the authenticity of the two Manetho passages that are the entire basis of Meyer’s thesis pose “the most difficult problem in Classics”? Really?

Sorry but I still don’t understand. How would you sum up Assmann’s thesis? What is his argument?

I have been avoiding one detail you mention till now. You speak about the “nature of the evidence” being other than what it seems, and of course it goes without saying that documents can never be merely assumed to be what they are at face value. But your own view of the nature of the documents is itself not a foregone fact but is itself a hypothesis. And that, too, needs to be tested. How does your hypothesis explain the plague/exodus/counter-religion motifs cluster?

” How does your hypothesis explain the plague/exodus/counter-religion motifs cluster?”

I will get to that.

I admit I may be too close to the book to address some the main points but a bigger question Assmann is addressing is the fact of a religious hostility towards Egypt as expressed in Jewish religious writings and a corresponding hostile view of Asiatics as religiously suspect among the Egyptians.

Look, Assmann’s theories of normative inversion took me a very long way towards my current theory because what you call “Jewish religious writings” contain normative inversions of both Egyptian and Babylonian (and Yahwist!) religious practices, while embracing Hellenistic myths, ethics and philosophy. It is almost as if the Primary History were written to appeal to Hellenes while being repulsive to the native peoples of the Ptolemaic and Seleucid empires. Hmmmmm.

My problem with Assmann is that he assumes away a huge body of work questioning the authenticity of those two Manetho fragments. In fact, he does not even mention this body of work, instead choosing to gild the lily with works that came after Manetho and that many scholars believe may well have been the basis for the interpolated passages upon which Assmann relies to create the basis of a “motif” that would not exist otherwise. He should have admitted and addressed the problems with his evidence. It was intellectually dishonest not to do so, which does not make me happy at all because my own hypothesis was inspired in many ways by his theory of normative inversion.

As above — I am unable to respond because I really don’t understand your objections. What do you understand to be the nature or point of A’s argument re mnemohistory?

It certainly is good to survey all the ancient material possibly relating to the Jews, and Moses. And Assmann is quite ingenious. Though different conclusions might be reached from the same material.

Perhaps Scott Griffin is partially right in that the Hyksos were not fully Jewish in the modern sense. Though I hypothesize that some of them learned monotheism from the Egyptians, Akhenaton. And from following one human lord, possibly a Moses. Thus creating Judaism proper?

Other than forged passage added to Manetho, there is nowhere any indication that the “Hyksos” were the “Jews” (the word used in Josephus is Greek for “Judean”). I am not sure why you cling to the truth of that interpolation, which is widely viewed as suspect for a variety of reasons (I only gave a snippet of those assuming that you’d follow the link I gave you to read the rest).

Outside of the highly suspect mention by “Manetho” and the fact that the “Hyksos” were semitic (so were the “Canaanites”), what is your basis for believing the Hyksos and the Jews? Maybe a better question is why do you want the Hyksos to have become the Jews?