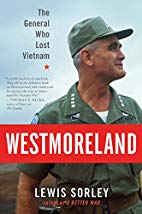

A few weeks ago, I was dealing with a mold issue in our RV’s bathroom. (Note: If you see mushrooms growing out of a crack in the wall, it’s usually a bad sign.) Having resigned myself to working with gloves, wearing a mask, sitting uncomfortably on the floor for at least an hour, I resolved to find a long audio program on YouTube and let it play while I worked. I happened upon a presentation by Dr. Lewis Sorley, based mainly on his book, Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam. (You can find the video at the end of this post.)

A few weeks ago, I was dealing with a mold issue in our RV’s bathroom. (Note: If you see mushrooms growing out of a crack in the wall, it’s usually a bad sign.) Having resigned myself to working with gloves, wearing a mask, sitting uncomfortably on the floor for at least an hour, I resolved to find a long audio program on YouTube and let it play while I worked. I happened upon a presentation by Dr. Lewis Sorley, based mainly on his book, Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam. (You can find the video at the end of this post.)

I had studied the Vietnam War as an undergraduate history major back in the 1980s, so much of what Sorley had to say covered old ground for me. Back in those days, of course, we could still refer to it as America’s Longest War without worrying whether some other disastrous Asian war might overtake it. After all, we had “learned the lessons of Vietnam,” right?

Later, as a student at Squadron Officer School, I certainly thought we had learned those lessons. From a policy perspective, the first lesson had to be clarity of purpose. On the military side, we would never again fight a limited war of attrition; instead, we would use overwhelming force to achieve clear objectives. In a nutshell, this is the “Get-In-and-Get-Out” Doctrine: Know your objectives. Achieve them in minimum time with minimal loss of life.

We would absolutely avoid any future quagmires. Or so we thought.

I should mention that several other lessons — both spoken and unspoken — arose out of the Vietnam experience. The practice of embedding journalists within fighting units came out of the beliefs that the press should not have been permitted to work as independent observers and that allowing them to move freely in South Vietnam had been a mistake.

An expanding set of myths about why we lost the war blossomed quickly into an alternate history in which unreliable draftees, fickle politicians in Washington, pinko journalists, and the hippy peace movement conspired to keep us from winning.

Some of these myths took hold naturally, as veterans told their personal stories, relating with frustration how the body counts didn’t seem to matter, that the V.C. would return again and again, that the stupid war of attrition didn’t work, and what’s more, nobody seemed to give a damn that it wasn’t working. That much was true.

Continue reading “Some Thoughts on the Lessons of Vietnam and the General Who “Lost” the War”