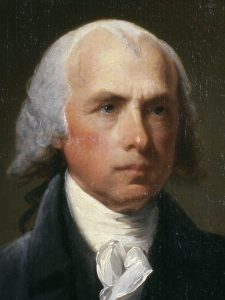

The first eight words in the alleged quotation below by James Madison, below, are false.

Here’s what Madison said about democracy:

Democracy is the most vile form of government . . . democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention: have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property: and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths. [The text in boldface is pure fiction.]

The Founders just didn’t trust the ordinary people and deliberately kept them at arm’s length, as can be seen from the way they drafted the Articles of Confederation and then the U.S. Constitution. (Arnheim 2018, p. 25)

Certain conservative authors insist these words from James Madison prove that the framers of the U.S. Constitution distrusted ordinary people and hated democracy. The above example comes from Michael Arnheim (Ph.D., ancient history) who is, according to the editors of the “for Dummies” series, “uniquely qualified to present an unbiased view of the U.S. Constitution.” (Arnheim 2018, back cover)

Uniquely qualified?

Dr. Arnheim provides no citation for the Madison quote, but you can find the true part in Federalist 10. Since so many versions and editions of the Federalist Papers exist, I’ll cite paragraph numbers rather than page numbers.

Before continuing, however, please be aware that the mischief does not begin and end with the fictional denigration of democracy. Conservatives will often, as Arnheim does, neglect to define the term, knowing that modern readers will conflate the common term “representative democracy” with Madison’s “pure democracy.”

We shouldn’t discuss terms like “constitution,” “republic,” and “democracy” as if they were simple English words. In the context of government, or in this specific case — a history of the U.S. Constitution — these are terms of art. We need to know how the authors at the time defined these terms in order to deal with them honestly. Fortunately, Madison et al. often gave perfectly concise definitions of the terms at hand. On the subject of democracy, he wrote: Continue reading “How Did We Get Here? (Part 3) Are Democracies “Vile”?”

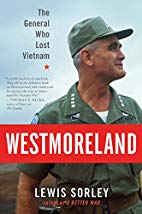

A few weeks ago, I was dealing with a mold issue in our RV’s bathroom. (Note: If you see mushrooms growing out of a crack in the wall, it’s usually a bad sign.) Having resigned myself to working with gloves, wearing a mask, sitting uncomfortably on the floor for at least an hour, I resolved to find a long audio program on YouTube and let it play while I worked. I happened upon a presentation by Dr. Lewis Sorley, based mainly on his book,

A few weeks ago, I was dealing with a mold issue in our RV’s bathroom. (Note: If you see mushrooms growing out of a crack in the wall, it’s usually a bad sign.) Having resigned myself to working with gloves, wearing a mask, sitting uncomfortably on the floor for at least an hour, I resolved to find a long audio program on YouTube and let it play while I worked. I happened upon a presentation by Dr. Lewis Sorley, based mainly on his book,