Earlier posts in this series:

- Jesus Mythicism and Historical Knowledge, Part 1: Historical Facts and Probability

- Jesus Mythicism and Historical Knowledge, Part 2: Certainty and Uncertainty in History

—o0o—

For Richard Carrier the methods of scientific and historical research overlap and are different from each other only in degree:

Science and history are thus inseparable. But the logic of their respective methods is also the same. The fact that historical theories rest on far weaker evidence relative to scientific theories, and as a result achieve far lower degrees of certainty, is a difference only in degree, not in kind. Historical theories otherwise operate the same way as scientific theories, inferring predictions from empirical evidence—both actual predictions as well as hypothetical. (Proving History, 48)

Here I believe Carrier is mistaken about both the historian’s and the scientist’s methods. If there is any consolation it may be found in learning that the nineteenth philosopher John Stuart Mill made the same mistake in his attempt to describe scientific method and Mill was followed in the social sciences for many decades.

What Is a Scientific Theory?

Scientific theories do not arise naturally from observing empirical evidence:

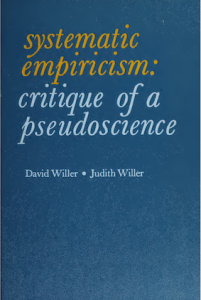

Timing the fall of a variety of objects such as leaves, paper, cannon balls, rocks, boards, and automobiles running off cliffs has little (if any) utility for the development of a useful theory of falling bodies. One could run correlations between the weight of such objects and their time of fall for many lifetimes without ever accumulating the sort of knowledge conducive to theoretical thinking about falling bodies. (Systematic Empiricism, 29f)

Albert Einstein himself wrote:

. . . theory cannot be fabricated out of the results of observation . . . (Systematic Empiricism, 103)

In these posts I am presenting my view of “what history is” and “how history is done” that is at odds with Carrier’s empiricism. I reject the notion that the most historians can say about any past event is that it “probably” happened. Carrier makes his position clear early in Proving History:

If anyone rejects my axioms, then no further dialogue is possible on this issue until there is agreement on the broader logical and philosophical issues they represent. Producing such agreement is not the point of this book, which is only written for those who already accept these axioms (or who at least agree they should). . . .

Axiom 4: Every claim has a nonzero probability of being true or false (unless its being true or false is logically impossible). . . .

All claims have a nonzero epistemic probability of being true, no matter how absurd they may be (unless they’re logically impossible or unintelligible), because we can always be wrong about anything. . . .

Therefore, because we only have finite knowledge and are not infallible, apart from obviously undeniable things, some probability always remains that we are mistaken or misinformed or misled. . . . And although the probability that a given claim is true (or false) may be vanishingly small and thus practically zero, it is never actually zero. It’s vital to admit this.

(pp 20, 23, 24, 25 – my bolding apart from “Axiom 4”)

I do reject this axiom. Even though I am not omniscient or infallible, it does not follow that there might be even the slightest chance that I am wrong to believe many historical events did indeed happen: the English, American, French, Russian revolutions, for example, or the Seven Years War, the Napoleonic War, World War I, or in the past reality of figures like Winston Churchill, Oliver Cromwell, Martin Luther, or Julius Caesar. That many Jews, communists, Roma and disabled were murdered under Hitler’s regime in an event known as the Holocaust is as undeniable as the fact that you are reading these words right now. Probability does not enter the historicity of these events at all. Probability enters only with respect to justifying interpretations, reasons, results or the scale of such events. They happened and our knowledge that they happened or existed is absolutely certain. We don’t need to know everything about them to have absolute confidence; the possibility that we are mistaken in our assurance that these things happened or that these persons existed really is zero.

So my intention is to place my contrary perspective on history — one that I think is accepted by the majority of professional historians — for consideration as another point of view from Carrier’s.

So what is a scientific theory, then, and how does it come about?

Scientific theory is concerned with concepts, terms not defined by reference to observation, which consequently enter into exact theoretical relations with one another which are often expressed mathematically. . . . The purpose of theory in science is to explain, predict, and guide new research. But empiricist social theorizing consists of nothing more than generalizing, a process which summarizes what has been observed. A summary of past observations, however, cannot explain and predict, and accuracy cannot be gained from vagueness. . . .

The creation of a useful theory requires the abstraction of a pure structural model from the diverse material of observation. In other words, abstraction does not proceed by summarizing observations, but by generating a nonobservational structure which deliberately does not summarize. The abstractive process, because it links theory to observation, is never complete without both. Theory, on the other hand, can be applied only through abstraction.

A theory is a constructed relational statement consisting of nonobservable concepts connected to other nonobservable concepts. Concepts are defined not in terms of observations but by their relationship to each other. Although it may be meaningful to state “There is a cow,” the statement “There is a force” is senseless because force is not an observable. Conversely, the statement “Force is equal to mass times acceleration” is meaningful because nonobservable concepts can be related through mathematical connectives; but the statement “Cow equals four legs” is meaningless because observational terms cannot be so related. In other words, the truth of scientific theories is not an empirical truth based on observation; it is a consequence of form, the relationship of nonobservables. (Systematic Empiricism, 3, 24 – my bolding in all quotations)

No historian, nor indeed any social scientist, has ever produced a theory of the scientific kind to explain and predict social and historical events. Scientific theories and research have . . .

. . . resulted in explanation and prediction of phenomena . . .

but they have done so

through the rational cumulation of laws. (Systematic Empiricism, 6)

Theories and laws provide the framework through which the physical world is understood by the scientist.

What Carrier is doing is describing the data available to historians and drawing generalizations from subsets of it. Finding more data that is consistent with other known data does not involve making a prediction. It is simply describing the information we acquire from the data.

Can Historians Make Predictions?

Carrier argues that historians, like scientists, can make predictions on the basis of their “theories”:

And just as a geologist can make valid predictions about the future of the Mississippi River, so a historian can make valid (but still general) predictions about the future course of history, if the same relevant conditions are repeated (such prediction will be statistical, of course, and thus more akin to prediction in the sciences of meteorology and seismology, but such inexact predictions are still much better than random guessing). Hence, historical explanations of evidence and events are directly equivalent to scientific theories, and as such are testable against the evidence, precisely because they make predictions about that evidence.

In truth, science is actually subordinate to history, as it relies on historical documents and testimony for most of its conclusions (especially historical records of past experiments, observations, and data). Yet, at the same time, history relies on scientific findings to interpret historical evidence and events. Science and history are thus inseparable. But the logic of their respective methods is also the same. The fact that historical theories rest on far weaker evidence relative to scientific theories, and as a result achieve far lower degrees of certainty, is a difference only in degree, not in kind. Historical theories otherwise operate the same way as scientific theories, inferring predictions from empirical evidence—both actual predictions as well as hypothetical. Because actual predictions (such as that the content of Julius Caesar’s Civil War represents Caesar’s own personal efforts at political propaganda) and hypothetical predictions (such as that if we discover in the future any lost writings from the age of Julius Caesar, they will confirm or corroborate our predictions about how the content of the Civil War came about) both follow from historical theories. This is disguised by the fact that these are more commonly called ‘explanations.’ But theories are what they are. (Proving History, 47f)

In truth, science is actually subordinate to history, as it relies on historical documents and testimony for most of its conclusions (especially historical records of past experiments, observations, and data). Yet, at the same time, history relies on scientific findings to interpret historical evidence and events. Science and history are thus inseparable. But the logic of their respective methods is also the same. The fact that historical theories rest on far weaker evidence relative to scientific theories, and as a result achieve far lower degrees of certainty, is a difference only in degree, not in kind. Historical theories otherwise operate the same way as scientific theories, inferring predictions from empirical evidence—both actual predictions as well as hypothetical. Because actual predictions (such as that the content of Julius Caesar’s Civil War represents Caesar’s own personal efforts at political propaganda) and hypothetical predictions (such as that if we discover in the future any lost writings from the age of Julius Caesar, they will confirm or corroborate our predictions about how the content of the Civil War came about) both follow from historical theories. This is disguised by the fact that these are more commonly called ‘explanations.’ But theories are what they are. (Proving History, 47f)

What Carrier refers to as a prediction by a historian is really nothing more than a description of the relevant data found in the sources. A hypothesis formulated from the data can hardly claim to predict what is in the dataset. Rather, the hypothesis is tested for consistency with the data, but that’s not a prediction. In On the Historicity of Jesus Carrier regularly refers to what he finds in the sources as being “expected” by his hypothesis that Jesus was a mythical creation and not a historical person. I suggest, however, that the very notion of a “mythical” Jesus has arisen from a raft of studies on the question ever since the late eighteenth century and has been shaped by those studies and their interpretations of the New Testament. Carrier says, for example, on page 581 of On the Historicity that the idea that Jesus came from the seed of David — as per Romans 1:3 — could have been predicted by his hypothesis of mythicism:

So Paul’s reference to Jesus being ‘made’ (genomenos) of the ‘seed’ (sperma) of David and being ‘made’ (genomenos) from a woman are essentially expected on minimal mythicism . . . .

So Paul’s reference to Jesus being ‘made’ (genomenos) of the ‘seed’ (sperma) of David and being ‘made’ (genomenos) from a woman are essentially expected on minimal mythicism . . . .

Instead, if we start with minimal mythicism, we can easily predict the original kernel to most likely have been that Jesus was indeed made from a celestial sperm that God snatched from David, by which God could fulfill his promise to David against the appearance of history having broken it. That this fits what we read in Paul therefore leaves us with no evidence that Paul definitely meant anything else. . . .

Minimal mythicism practically entails that the celestial Christ would be understood to have been formed from the ‘sperm of David’, even literally (God having saved some for the purpose, then using it as the seed from which he formed Jesus’ body of flesh, just as he had done Adam’s). I do not deem this to be absolutely certain. Yet I could have deduced it even without knowing any Christian literature, simply by combining minimal mythicism with a reading of the scriptures and the established background facts of previous history. And that I could do that entails it has a very high probability on minimal mythicism. It is very much expected. (On the Historicity, 581f)

In Proving History Carrier speaks of the historian’s hypothesis being able to predict “what type of evidence to expect” — that is, the evidence that his hypothesis “predicts”:

. . . the evidence we have is exactly what we should expect if the story was made up . . .

Specifying the ‘type’ of evidence to expect in this way allows wide ranges of possible outcomes . . . .

One must thus distinguish ‘predictions of exact details’ (which BT does not concern itself with in this case) from ‘predictions regarding the type of evidence to expect.’ . . .

. . . the evidence can fit our hypothesis fine, being entirely what we should expect . . .

It’s sufficient to construct h to make . . . generic predictions (predictions of what type of evidence to expect) (On the Historicity, 58, 77, 78, 167, 214)

Leaving aside the tautology (expectation is a kind of prediction, isn’t it? — Carrier means “predictions of what type of evidence we will find”) I suggest that the only reason Carrier could “predict” finding a text saying Jesus came from the seed of David is because he knew it was in the database to begin with and that he could not formulate a hypothesis about a nonhistorical Jesus that contradicted it. Indeed, his starting hypothesis had to allow room for what he knew to be in the database. Romans 1:3 had been widely discussed and debated among both Jesus mythicists and Jesus historicists by generations of scholars. That there is no real prediction involved can be assessed by a Bayesian analysis itself. We have historical records testifying to Judeans entertaining a wide range of notions about the messiah or similar figure to come and relatively few seemed to have made the same “prediction” Carrier speaks of:

- Some used Scriptures to argue he would come from Joseph, not David.

- Some used the same Scriptures to determine there would be two messiahs.

- Some said that no-one would know his genealogy.

- Some said he would be hidden and no-one would know where he was.

- The canonical gospels even indicate some debate among early Christians over whether he really was descended from David or not.

- And on top of all of that a few scholars have offered reasons to think that the relevant passage in Paul’s letter to the Romans about Jesus and the seed of David was a late interpolation — that is, that Paul did not write it anyway!

So the sources themselves tell us that there were many notions about a future messianic figure and only a few of them linked that figure to David, so by relying on our “background knowledge” of messianic predictions we would have to say that a Bayesian assessment of the hypothesis that Paul’s claim could have been genuinely “predicted” is that it is unlikely.

As if to underscore the pointlessness of Carrier’s “prediction” that Paul’s passage was of a kind of evidence that was foreseen by Carrier’s hypothesis, he concedes that the same passage could be predicted with twice the probability of being found by the opposing hypothesis (p. 581). Of course, Carrier also argues that the cumulation of evidence and attendant probabilities outweighs mathematically the success rate of all the other “predictions” of the Jesus historicists.

Nothing is predicted or explained if the event itself is more certain than the law supposedly explaining it. The event is a test of the statement, not a prediction from it. (Systematic Empiricism, 130)

I covered other aspects of this question of prediction in historical research in the previous two posts.

Experimental Testing

Carrier further equates history with science by pointing out that both fields do sometimes perform experiments to test theories.

Historical methods are identical to scientific methods in this respect, being just another set of iterations of [the Hypothetico-Deductive Method]. In fact, many sciences are historical, for example, geology, cosmology, paleontology, criminal forensics, all of which explore not merely scientific generalizations but historical particulars, such as when the Big Bang occurred, or how the solar system formed, or exactly when or where a large asteroid struck the earth, or when a volcano erupted and what resulted from it, or what happened to a specific species in a specific historical period, or who committed what crime when. Not even the claim that historians must deal with human thoughts and intentions makes a difference, as these are as much a necessary occupation of psychologists, economists, sociologists, and anthropologists. It’s also fundamental to the scientific study of game theory and all of cognitive science. Nor is there any demarcation based on the role of controlled experiments. Much of science does not rely on experiments but primarily involves field observations (e.g., astronomy, zoology, ecology, paleontology), an approach to evidence directly analogous to the historian (most clearly parallel in the science of archaeology, but “field observations” of the artifacts we call “texts” and “documents” is just as analogous). Conversely, experiments sometimes do have a place in historical methodology. 10

10 For some examples, see my essay on “Experimental History,” July 28, 2007, at http://richardcarrier.blogspot.com/2007/07/experimental-history.html (Proving History, 105, 308

The examples on the linked page contain a discussion of what a certain type of ancient Greek ship actually looked like and how it might have functioned. Not only historians are often fascinated by what techniques ancients might have employed for all sorts of things. But those kinds of experiments are not the kind that relate to the kinds of events that interest most historians. We cannot replicate and experiment conditions of human behaviour to test this or that explanation for, say, a war. To refer back to J. and D. Willer,

Empiricist induction is based on likeness, but lab experiments are by definition unlike natural cases and thus any inductions from them for application in social circumstances are illegitimate. . . . Only the field experiment is logically capable of generating results satisfying the systematic empiricists’ criteria and then only if the empirical power of the researcher is strong enough to effectively (or absolutely) control the empirical circumstances. But until sociologists become philosopher kings or are delegated total power over the environment of their experiments by a totalitarian government, the field experiment is as useless as the others. (Systematic Empiricism, 135f)

Does the Hypothetico-Deductive Method Make Prediction Possible?

As for the value of the hypothetico-deductive method for making predictions,

. . . “Pure logic” cannot draw necessary conclusions by deduction from inductive general statements. The only general statements which can lead to true necessary conclusions in pure logic are those which are “true” by definition, and these are nonpredictive. If it is true by definition that all swans are white we simply do not admit the existence of black swans but call those birds which look like swans but are black by some other name (“snaws”). We cannot predict that if we find a swan he will be white but we will call “swans” only birds which we observe to be white. (Systematic Empiricism, 126)

. . . “Pure logic” cannot draw necessary conclusions by deduction from inductive general statements. The only general statements which can lead to true necessary conclusions in pure logic are those which are “true” by definition, and these are nonpredictive. If it is true by definition that all swans are white we simply do not admit the existence of black swans but call those birds which look like swans but are black by some other name (“snaws”). We cannot predict that if we find a swan he will be white but we will call “swans” only birds which we observe to be white. (Systematic Empiricism, 126)

Consequently . . .

Consequently no empirical generalization can act as a major premise in a deductive explanation, and empirical generalizations can never be used deductively to explain or predict. . . .

Scientific explanation cannot be deductive because scientific laws are statements relating nonobservable concepts, such as force, mass, and acceleration in terms of nonobservable connectives such as an equivalence or an equals sign. (Systematic Empiricism, 130f)

In 1942 the Journal of Philosophy published a paper arguing, like Carrier seventy years later, that historical methods were scientific. The Willers in response write, in part,

It comes as no surprise that Hempel cites no general laws in that paper and shows no application to history; but at the same time he refers to a “metaphysical theory of history,” apparently intending this label to apply to Karl Marx. From an empiricist view of science Marx may very well have presented a “metaphysical theory,” but from the viewpoint of scientific knowledge systems this intended negative criticism is actually a compliment to Marx, who (unlike those who search for empirical “patterns” in history) based his view of history on theoretic relations of concepts. (Systematic Empiricism, 129)

History, a Very Bad Predictor of Future Events

So convinced is Carrier of his status of history as a scientific process that he believes history can be used to predict not only what evidence will be found but even the future itself. This is empiricism with a vengeance.

And just as a geologist can make valid predictions about the future of the Mississippi River, so a historian can make valid (but still general) predictions about the future course of history, if the same relevant conditions are repeated (such prediction will be statistical, of course, and thus more akin to prediction in the sciences of meteorology and seismology, but such inexact predictions are still much better than random guessing). Hence, historical explanations of evidence and events are directly equivalent to scientific theories, and as such are testable against the evidence, precisely because they make predictions about that evidence. (Proving History, 47)

No, they cannot. The reason is that the same conditions are never repeated in human affairs. We can have fears, hopes and plans for the future, but we can never predict it — except in hindsight! In hindsight what happens seems to have been inevitable. But only in hindsight.

While many people, especially politicians, try to learn lessons from history, history itself shows that very few of these lessons have been the right ones in retrospect. Time and again, history has proved a very bad predictor of future events. This is because history never repeats itself; nothing in human society, the main concern of the historian, ever happens twice under exactly the same conditions or in exactly the same way. And when people try to use history, they often do so not in order to accommodate themselves to the inevitable, but in order to avoid it. (In Defence of History, 50)

While many people, especially politicians, try to learn lessons from history, history itself shows that very few of these lessons have been the right ones in retrospect. Time and again, history has proved a very bad predictor of future events. This is because history never repeats itself; nothing in human society, the main concern of the historian, ever happens twice under exactly the same conditions or in exactly the same way. And when people try to use history, they often do so not in order to accommodate themselves to the inevitable, but in order to avoid it. (In Defence of History, 50)

As for history being on a par with science in its methods, and keeping in mind Carrier’s frequent appeals to geologists being able to predict the future, Evans concludes:

History, in the end, may for the most part be seen as a science in the weak sense of the German term Wissenschaft, an organized body of knowledge acquired through research carried out according to generally agreed methods, presented in published reports, and subject to peer review. It is not a science in the strong sense that it can frame general laws or predict the future. But there are sciences, such as geology, which cannot predict the future either. (In Defence of History, 62)

In the next and final post in this series I will tie the points raised directly to the question of the historicity of Jesus and Carrier’s approach in particular.

Carrier, Richard. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield Phoenix, 2014.

Carrier, Richard. Proving History: Bayes’s Theorem and the Quest for the Historical Jesus. Prometheus Books, 2012.

Evans, Richard J. In Defence of History. Norton, 1997.

Hempel, Carl G. “The Function of General Laws in History.” The Journal of Philosophy 39, no. 2 (January 15, 1942): 35. https://doi.org/10.2307/2017635.

Willer, David, and Judith Willer. Systematic Empiricism: Critique of a Pseudoscience. Prentice-Hall, 1973. https://archive.org/details/systematicempiri0000will

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Re “Timing the fall of a variety of objects such as leaves, paper, cannon balls, rocks, boards, and automobiles running off cliffs has little (if any) utility for the development of a useful theory of falling bodies. One could run correlations between the weight of such objects and their time of fall for many lifetimes without ever accumulating the sort of knowledge conducive to theoretical thinking about falling bodies. (Systematic Empiricism, 29f)”

This is rather astonishing in that Galileo’s timing of balls rolling down a plank was the first scientific law to be quantified. Which lead to newton, which lead to Einstein. Granted we still do not know the scource of gravitational forces but we are working on it.

As to comparing historical and scientific methods, I think the exercise is probably not worth the trouble. (I think Carrier was a little too over-sensitized to critics of his methods and over-defended them.) The natural sciences have a final arbiter of whether our thinking is good or not . . . nature. If we, as scientists, get too far out there, Mother Nature bitch-slaps us back into line. The social sciences have no such final arbiter and so their methods have, as Carrier rightly insists, lower probabilities. In my lifetime the “Social Sciences” were known as “Social Studies” but when science began achieving a great deal of street cred, all kinds of things got renamed to include the word “science” to bask a bit in reflected glory. The Pseudo-Nobel Prize in economics is called the “… Prize for the Economic Sciences.” Economists even mathematized up their topic, for no actual profit, to make it look more sciency.

The point is that Galileo was abstracting from experience, formulating abstract concepts that apply to all of experience. What was formulated was an abstract law to explain how all bodies act:

Galileo wrote of his method in a letter:

Lindsay, R. B. “Galileo Galilei, 1564–1642, and the Motion of Falling Bodies.” American Journal of Physics 10, no. 6 (December 1, 1942): 285–92. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.1990402.

Galileo was seeking to understand the idea of motion by formulating abstract concepts. He was not studying the motions of objects themselves to see what they had in common.

(You are probably aware, but I mention it here for the record, that the story of Galileo dropping balls from the leaning tower of Pisa is very likely “an urban legend”. There is no contemporary evidence for that event.)

In other words, it was the abstract theory that led to the demonstration with the planks, not the demonstration that led to theory.

Does this help?

Dictionary

Definitions from Oxford Languages · Learn more

sci·ence

/ˈsīəns/

noun

1.

the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation, experimentation, and the testing of theories against the evidence obtained.

“the world of science and technology”

Similar:

branch of knowledge

area of study

discipline

field

2.

archaic

knowledge of any kind.

“his rare science and his practical skill”

The biggest devil is in the word “theories”, is it not? That is where there is no comparison between science and history. I think my concluding quote in the post from Evans got it right.

Though Carrier does attempt to say history does perform experiments to some extent…. http://richardcarrier.blogspot.com/2007/07/experimental-history.html

It seemed to me the biggest distinction under definition (1) was that history is not mainly concerned with the “structure and behavior of the physical and natural world.” There would be no need for reliance on mathematical probability assessments. In fact, they would have no real meaning, and I don’t think Carrier’s do, although I agree with his overall conclusion. Under definition (2), there is no distinction.

Indeed. Carrier would respond, however, that historical methods of inquiry and explanation are no different in principle (only in degree) from those of the scientific studies of the physical and natural world. He is repeatedly explicit about that view in Proving History.

I read OHJ, but not PH. However, how can math become necessary in a history of a civil war the way it would be necessary to calculate the speed necessary for an airplane to achieve lift?

Carrier acknowledges that while maths is not necessary in assessing historical claims it is nonetheless helpful insofar as it can assist historians in clarifying the different weights and probabilities they otherwise subconsciously attribute to specific strands of evidence. Further, Carrier would say that even the claim that a plane will get off the ground has a probability factor built into it — the hope of the engineers that it will do so is embeds vanishingly small doubt that it won’t, so that they can in practical terms say that it definitely will get off the ground despite the necessary theoretical room for even the slimmest of doubts. By framing all events, both those in the natural world and those in the human world, in terms of probability this way, he attempts to assert an equality of kind between the claims and even methods of history and those of science, the differences being only in degree.

I share your reservations.