Two weeks ago I posted my notice of a translation of Gustav Volkmar’s 1857 study of the Gospel of Mark that had been written for a general audience. This post is to notify interested readers of the availability of a translation of his far more academic 1876 work, Mark and the Synopsis of the Gospels according to the Documentary Text and the History of the Life of Jesus. Volkmar was clearly devoted to Jesus as the historical figure who changed the world but his study of the gospel narratives is intriguing for its scholarly and pioneering approach to identifying the sources of the Gospel of Mark, including his view that it was in part a reaction against the Book of Revelation. See the extract below of an essay by Anne Vig Skoven for further details.

Below is a copy of the static page that is now available in the right hand margin of this blog.

I have now translated two of Gustav Volkmar’s works:

- The Religion of Jesus (1857);

- Mark and the Synopsis of the Gospels (1876).

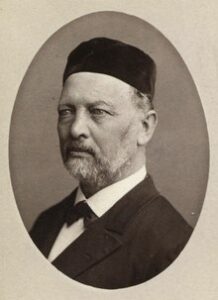

Gustav Volkmar (1809-1893) has been referenced a few times in this blog but the most detailed synopsis of his views on the Gospel of Mark came from a post by Roger Parvus: A Simonian Origin for Christianity, Part 16: Mark as Allegory

The following notes are taken from

- Skoven, Anne Vig. “Mark as Allegorical Rewriting of Paul: Gustav Volkmar’s Understanding of the Gospel of Mark.” In Mark and Paul. Part II, For and against Pauline Influence on Mark: Comparative Essays, edited by Eve-Marie Becker, Troels Engberg-Pedersen, and Mogens Müller, 13–27. Beihefte Zur Zeitschrift Für Die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft Und Die Kunde Der Älteren Kirche; Volume 199. Berlin, Germany ; Boston, Massachusetts: De Gruyter, 2014. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110314694.13/html?lang=en

.

[Anne Vig Skoven who wrote this essay was a PhD student at the University of Copenhagen until her tragic, premature death in 2013]

Unlike exegetes of the patristic tradition and also unlike most of 20th century scholarship, biblical scholars of the 19th century were not foreign to the idea that Paulinism was to be found in the Gospel of Mark. The founder of the so-called Tubingen School, Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792-1860), for instance, regarded the Gospel of Mark as a synthesis of Petrine and Pauline traditions. . . .

In 1857, the German exegete Gustav Hermann Joseph Philipp Volkmar (1809-93) characterized the Gospel of Mark as a Pauline gospel. Although Mark’s story was concerned with Jesus’ life and death, it was also, so Volkmar argued, permeated by Pauline theology. During his lifetime, Volkmar remained a solitary figure, and David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874) once considered him a “närriger Kauz” [= a ludicrous little owl]. Nevertheless, at the end of the 19th century knowledge of Volkmar’s thesis and writings was widespread among German speaking scholars. His thesis drove a wedge into German biblical scholarship; Adolf Jülicher (1857-1938) and William Wrede (1859-1906) both appreciated Volkmar’s work, Albert Schweizer (1875-1965) and his student Martin Werner (1887-1964) did not. . . .

. . . . From 1833 to 1852, he taught in various Gymnasien, in which he primarily worked within the field of philology and classical studies. In 1850 he published a book on Marcion and the Gospel of Luke, in which he claimed against Baur and Albrecht Ritschl (1822- 1889) that Marcion’s gospel was a rewriting of Luke.’ According to Adolf Jülicher, Volkmar had deserved a chair for this – today widely accepted – thesis. However, a series of dramatic events prevented that. Due to church political controversies, Volkmar was arrested in the classroom in 1852 and charged with lese majesty and dismissed from his job. In 1853, he was called lo Zürich where he was finally appointed professor of New Testament studies in 1863. In Zürich he published the works which are of special relevance to the present study:

- Die Religion Jesu und ihre erste Entwickelung nach dem gegenwärtigen Stande der Wissenschaft (Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1857); a popular work, which introduced Volkmar’s thesis of Mark as a Pauline gospel.

- Die Evangelien, oder Marcus und die Synopsis der kanonischen und ausserkanonischen Evangelien nach dem ältesten Text mit historisch-exegetischem Commentar (Leipzig: Ludw. Fr. Fues Verlag, 1870); a scholarly commentary on the Gospel of Mark, in which Volkmar, against Baur, forwarded his thesis that Mark was the first gospel, Luke the second and Matthew only the third. The commentary was republished in a slightly edited second edition with a new title in:

- Marcus und die Synopse der Evangelien nach dem urkundlichen Text und das Geschichtliche vom Leben Jesu (Zürich: Verlag von Caesar Schmidt, 1876).

In addition to Volkmar’s traditional commentaries on the Markan text, the books from 1870/76 offer an early reception history of the Markan narratives. . . . .

In his biographical sketch of Gustav Volkmar from 1908, Adolf Jülicher characterizes Volkmar as an exegete whose work was framed to the one side by Baur’s Tendenztheorie and to the other side by Strauss’ scepticism (772 f). Yet, he differs from both schools on two important issues: historicity and Markan priority. With regard to Strauss, Volkmar welcomes his critique of the rationalistic and harmonizing exegesis of early 19th century scholarship. But he is also critical of Strauss’ concept of the gospel narratives as mythoi, instead he prefers the term “Poësie”. Unlike Strauss Volkmar emphasizes the historicity of the gospel narratives.Yet, his understanding of historicity, as well as his method are closer to those of 20th century redaction criticism than to the Leben Jesu Forschung of his own century. With regard to the Tübingen School, Volkmar treats the early Christian literature as Tendenzschriften. His overall project was to reconstruct the history of the gospel traditions as a reflection of the developments in early Christianity. But unlike the Tübingen exegetes, he accepted, as already mentioned, the thesis of Markan priority. Consequently, he rejected the idea of an “Ur-Evangelium” which was needed for the Tübingen explanation of the gospel relations. Likewise he rejected the idea of a Spruchbuch or Schriftquelle (1870, vili-xi; 1876, 646) – later identified as Q. According to Volkmar, Mark’s only sources were: the Old Testament writings, four Pauline letters (Romans, Galatians, 1 and 2 Corinthians), the oral tradition of early Christian communities – and, surprisingly, Revelation.

(pp 13-16)

The works I have translated and made available here are Volkmar’s 1857 Die Religion Jesu and Marcus und die Synopse der Evangelien (1876)