This post continues my series on Nanine Charbonenel’s Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure De Papier but this time I will begin with a personal experience. I posted about it a couple of years ago under the title The Faith Trick. The experience was the realization that the power by which I was “transformed into a new person” (as per Ephesians and Colossians) was my faith, my conviction, that it was so: it was my own faith in “the faithfulness of God” to transform me that doing it: here lay the dark and fearful dawning on my consciousness — that it would make no difference if the object of my faith were Jesus or a magic crystal, were a sheltering mountain or a leprechaun, if I believed the same things of them as I did of Jesus the personal result, the change in my own life, would be the same. I had been believing in metaphors and similes, figurative images, as if they had been absolute reality and even more real than the reality of physics and chemistry.

This post continues my series on Nanine Charbonenel’s Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure De Papier but this time I will begin with a personal experience. I posted about it a couple of years ago under the title The Faith Trick. The experience was the realization that the power by which I was “transformed into a new person” (as per Ephesians and Colossians) was my faith, my conviction, that it was so: it was my own faith in “the faithfulness of God” to transform me that doing it: here lay the dark and fearful dawning on my consciousness — that it would make no difference if the object of my faith were Jesus or a magic crystal, were a sheltering mountain or a leprechaun, if I believed the same things of them as I did of Jesus the personal result, the change in my own life, would be the same. I had been believing in metaphors and similes, figurative images, as if they had been absolute reality and even more real than the reality of physics and chemistry.

There is something remarkably powerful about the images, the figurative images, that make up the gospel story that has infused it with a power to dominate the Western landscape for close to two millennia.

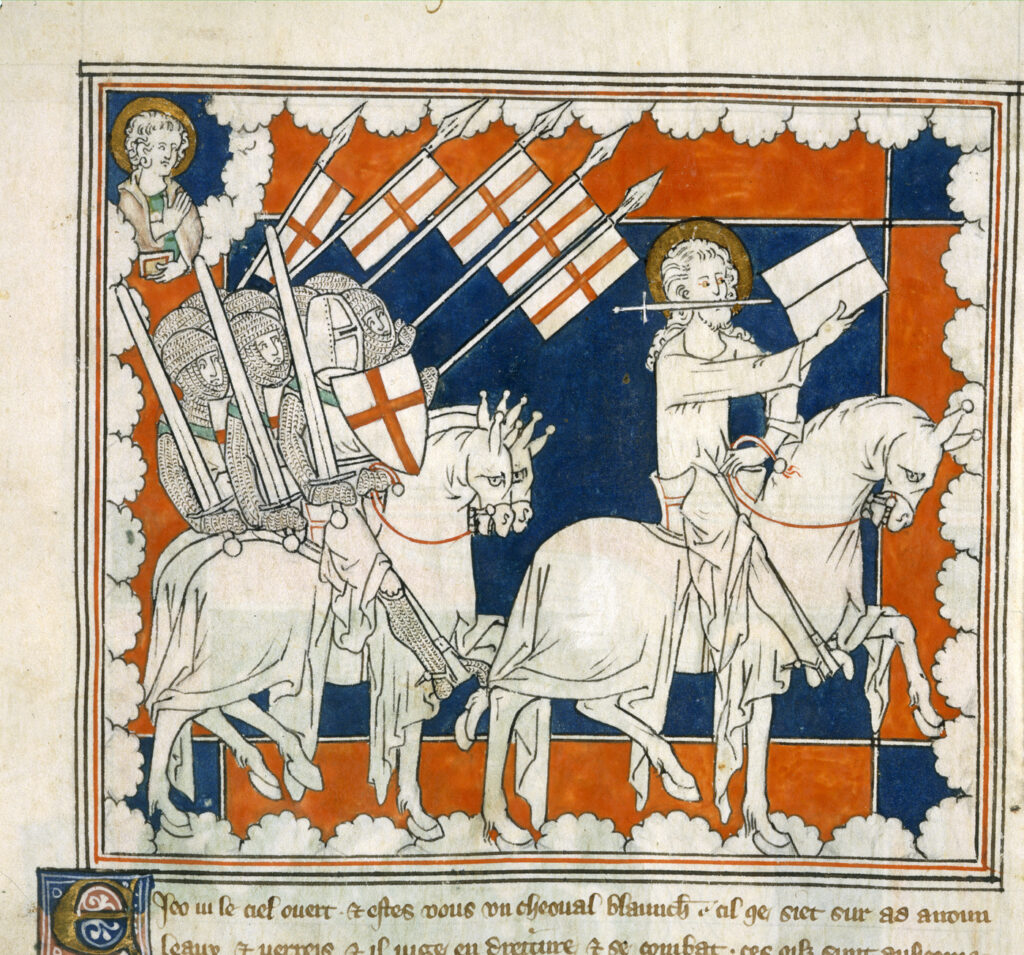

Let’s resume our discussion of NC’s study with this passage from the Book of Revelation ch 19:

Let’s resume our discussion of NC’s study with this passage from the Book of Revelation ch 19:

11 I saw heaven standing open and there before me was a white horse, whose rider is called Faithful and True. With justice he judges and wages war. 12 His eyes are like blazing fire, and on his head are many crowns. He has a name written on him that no one knows but he himself. 13 He is dressed in a robe dipped in blood and his name is the Word of God. 14 The armies of heaven were following him, riding on white horses and dressed in fine linen, white and clean. 15 Coming out of his mouth is a sharp sword . . . .

Is that rider on the white horse who wages war, whose eyes are fire, who wears multiple crowns and who has a secret name, a literal person? Is the vision of John that we are reading here a vision of a literal, true, flesh and blood person? Of course not (though I suspect a good number of Christian readers of that text would be more likely to hesitate and say Yes, it is, only not “flesh and blood” in the earthly sense). How do we know? The obvious giveaway is the name: the author tells us that the vision is a metaphor of the “Word of God”. The Word of God is what will judge the world, according to this text. But even that turn of phrase is metaphorical – a personification. In reality, a word is merely a pattern of sound or shapes of lines that humans have encoded to register a certain meaning. It is hard to get beyond the metaphors, the personifications, when one thinks deeply about the teachings of Christianity.

* This is not the place to explore other arguments that identify different strands of Christian traditions in the various canonical texts.

** C’est bien l’équivalent apocalyptique de Jésus. Pourquoi alors reconnaître que «Le Verbe de Dieu est le nom propre du cavalier eschatologique. La parole est identifiée à une personne»[quoting Frédéric Manns], et ne pas saisir le même processus dans les Évangiles? (p 431)

The reader of the Christian canon recognizes the above figure as the apocalyptic equivalent of the Jesus encountered in the gospels.* NC asks** rhetorically, why, since we can recognize that the Word of God is being personified in the end-time horseman, do we fail to grasp the same personification at work in the gospels.

As we have seen NC demonstrate in the previous posts, literary figures of speech have taken on ontological realities and dimensions in their own right, existences beyond mere metaphors and similes. Reality is further confused with prolepsis (speaking of events that really belong to the future as if they were past history) and analepsis (the converse, removing past events to the present), so that prophecy is confused with history and history with prophetic sayings.

I am not fluent enough in French to grasp the full import of NC’s writings at this point so I will copy a passage in its original French and hope some readers can clarify the meaning for me. I think NC is saying in the following that the expression for “humbled oneself” is an extreme hyperbole (figure of speech) and never meant literally, but that it has been interpreted literally by the faithful readers. But I look forward to clarification on the third point listed here:

On pourrait montrer les rapports étroits des théologèmes chrétiens, avec ce que nous appelons des figures de rhétorique ontologisées, saisies dans un Régime sémantique qui n’est pas le bon. Ainsi il faudrait :

° non seulement rattacher Prolepse et prophétie,

° mais s’interroger sur l’étonnante proximité de grands dogmes avec des figures de rhétorique ontologisées : la Transfiguration, en grec Metamorphosè ; l’Ascension, en grec Analepsis, qui est aussi le nom de la figure de rhétorique qu’est non le retour en arrière, mais le saut (pseudo)-logique ; la Trinité et l’Hendyadin… ;

2 On le trouve aussi en 2 Cor. 10, 1 (« humble parmi vous »), et Jacques 1, 9.° et l’on pourrait rapprocher aussi la Kénose et la Tapinose. On sait que la kénose désigne, dans le célèbre passage de la Lettre aux Philippiens 2, 8, le ‘’vidage’’ que la divinité fait, et que juste après ce passage, apparaît le verbe tapeinoun (s’humilier volontairement). On le trouve aussi en Matthieu 18, 4 ; 23, 12 ; 11, 29 (l’adjectif tapeinos2 traduit dans ce dernier cas par « je suis doux et humble de coeur »). Or la Tapinôsis (en latin humiliatio, extenuatio) est en grec l’hyperbole négative, l’exagération voulue dans la dépréciation, la caractérisation apparemment dépréciative et à ne pas prendre en réalité comme telle.

The Christ story has long been acknowledged as containing a mystery at its core. NC cites from the fourth century the words of “Pseudo-Chrysostom”,

All that we know of Christ is not only a pure proclamation of the Word, but a mystery of piety. For the whole order of salvation of Christ is called a mystery because the mystery does not appear only in a pure letter, but is published in an act, in fact preached.”

And that, in a nutshell, is NC’s hypothesis. Christian teachings owe their success to the creative and superlative way they have combined realism and figurative techniques so that distinguishing reality from mere image, the physical from the moral, the natural from the artificial: these supposed opposites have become so intertwined that together they have emerged as new realities for believers.

We go back to the mid-nineteenth-century’s Ernest Renan, renowned as “the” pioneer of an attempt to recover “the historical Jesus” with his Life of Jesus, who arguably failed to grasp as fully as he might have the depth of the figurative character of his sources:

The figurative language of the gospels has always been an invitation to erroneous readings. As far back as Chrysostom, Ambroise and Cyrill we find that the parable of the rich man and Lazarus was interpreted literally. Notice once more from Chateaubriand’s account of his travels to Jerusalem:

Here the path, which was heading east-west reached a bend and turned north, and I saw, on the right hand, the place where Lazarus the beggar lay, and opposite, on the other side of the street, the house of the rich sinner.

‘There was a certain rich man, which was clothed in purple and fine linen, and fared sumptuously every day:

And there was a certain beggar named Lazarus, which was laid at his gate, full of sores,

And desiring to be fed with the crumbs which fell from the rich man’s table: moreover the dogs came and licked his sores.

And it came to pass, that the beggar died, and was carried by the angels into Abraham’s bosom: the rich man also died, and was buried;

And in hell he lift up his eyes, being in torments, and seeth Abraham afar off, and Lazarus in his bosom.’ (Luke 16:19-23)

Saint Chrysostom, Saint Ambrose and Saint Cyril believed that the story of Lazarus and the rich sinner was not simply a parable, but a true and established fact. The Jews themselves have preserved the name of the rich sinner, whom they call Nabal (see 1 Samuel:25).

Pope Gregory I of sixth-seventh century fame, known in history as “the Great”, came closer than he knew to identifying the game at play when he wrote in his 23rd Homily on the Gospels about the experience of the two disciples on the road to Emmaus:

Pope Gregory I of sixth-seventh century fame, known in history as “the Great”, came closer than he knew to identifying the game at play when he wrote in his 23rd Homily on the Gospels about the experience of the two disciples on the road to Emmaus:

[Jesus] exchanged a few words with them, reproached them with their slowness in understanding, explained to them the mysteries of Holy Scripture concerning him, and yet, their hearts remaining foreign to him for lack of faith, he pretended to go further. Feindre [Fingere] can also mean [in Latin] modeling; that’s why we call potters’ clay modelers [Figuli]. Truth, which is simple, did not do anything with duplicity, but it simply manifested itself to the disciples in its body as it was in their minds.

It was necessary to test them to see if, not yet loving him as God, they were at least capable of loving him as a traveler.

The passage alluded to is Luke 24:28 where the word for “pretended” is a “once only” in the gospels, προσεποιήσατο (prosepoiēsato), to seem, to shape or form into another appearance. The exegesis of the believer is to recognize the pretence and the hidden meaning behind it but nonetheless to still believe the pretence itself is another level of reality. Close, but so far. The last word of that verse is a form of the same Greek word used to translate the Hebrew Halakhah, to take one’s journey, πορεύωμαι (poreuōmai), another intriguing irony in the context of all that NC has been addressing up to this point.

NC introduced this section of her discussion with a look at a significant idea we read in Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. I found the language barrier just a little too far beyond my reach to share her thoughts in the way they surely deserve so I quote the section in its original French here. The theme is the phrase “as if”: recall where Paul instructs his converts to live in the remaining time they now have left (between the death and resurrection of Jesus and his return and “end of this world”) “as if” this present situation no longer has any relevance. They are to make use of the world and their place in the world but not to think of themselves as belonging to the world. They are to live an “as if” existence.

. . . the time is short. From now on those who have wives should live as if they do not; those who mourn, as if they did not; those who are happy, as if they were not; those who buy something, as if it were not theirs to keep; those who use the things of the world, as if not engrossed in them. For this world in its present form is passing away. — 1 Cor. 7:29-31

The Greek word translated as “form” is schema and means appearance or in some contexts, apparently, figurative language. I would be grateful to anyone who can help me with the key points NC makes of her discussion of another philosopher’s discussion of this passage. (I don’t mean to provide a mere literal translation, an easy enough task, but an explanation of the key ideas that I believe need to go beyond a merely literal translation.) Continue reading “The Secret of the Power Behind the Gospel Narrative (Charbonnel Continued)”