Dr Patrik Lindenfors, an associate professor at the Stockholm University, has asked me if I would be willing to help him by advertising his crowdfunded research project on this blog. I am honoured to do so and have just sent a donation to help out as well. He’s asking for public assistance because it’s outside his normal area of research.

His university website lists his areas of research and publications. He also has a personal webpage.

His Facebook page contains summaries of the new project.

The following is extracted from his webpage dedicated to explaining the project and the campaign for public assistance.

I propose to review potential placebo effects of religion and how these may explain why religious beliefs and practices are so common across human populations.

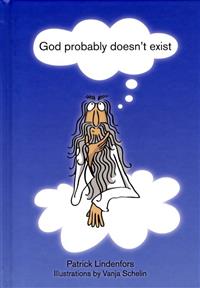

In my regular work I am a researcher of cultural evolution at Stockholm University. I have previously authored the books God Probably Doesn’t Exist, which has been translated into seven languages, and “Samarbete“, a popular science book in Swedish about the biological and cultural evolution of cooperation, currently being translated into English.

Now, I want to explore a proposal that has circulated in books and on-line discussions for a while – if there are any placebo effects of religion and whether these may be a partial explanation of the spread of religious beliefs and practices across human societies. . . . . .

You can read more and find out how to assist on the above links, in particular at the Divine Placebo webpage. Don’t delay though. He’s running out of time.

More from the site:

Scientific studies have found measurable effects of sham treatments on several different ailments – placebo effects. Religious rituals often invoke very similar mechanisms as those used to invoke such placebo responses, including suggestion, trust in authority figures, generated expectations and classical Pavlovian conditioning. In this way placebo (beneficial) and nocebo (detrimental) effects may function as religion’s stick and carrot, something which may have expedited the spread and maintenance of religious beliefs and rituals across human populations.

Importantly, placebos can provide actual benefits, resulting in both immediate and evolutionary advantages for people who are persuaded by pretend treatments and religious practices. This indicates real benefits of gullibility and suggestibility in humans, providing an explanation of the universal spread of religions across human populations. In the final chapter of the book I will discuss potential methods to harness the power of placebo for the benefit of the ever growing number of people who are not religious.

The field of evolutionary research on religion is exploding, with new research groups, journals and papers emerging all the time. Thus, there should be a ripe market for a book reviewing and summarizing a novel general argument.

I plan to write the book in English, in an easily accessible manner and with an anti-theistic slant, tapping into the large audience reading atheistic literature.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Comparing religion to drugs goes back to at least ancient Athens. For example, we know Plato wrote about it.

But I think framing the inquiry as one into placebo effects eclipses the underlying mechanisms that define human “rationality,” obscuring them from view and study.

As far as I can tell, human beings do not experience life, they interpret it by comparing what they observe to what they expect and acting according to the emotion evoked by that comparison. The more certain somebody is of their expectations, the more likely cognitive biases are to smooth over any differences between what was observed and what was expected, thus confirming that everything is okay. Whether somebody arrives at a high level of certainty through religion or secular ideology, the effects (and the consequences) are the same, and calling them “placebo effects” for religion while not doing so for secular ideologies seems misguided. A sense of false certainty shared throughout a society is what drives cultural evolution (or retards it). Instead of pretending that this basic feature of human cognition is pathological, perhaps we should accept it as normal.

Shared delusions of false certainty are a feature of a scalable society, not a bug.