Dazed and confused

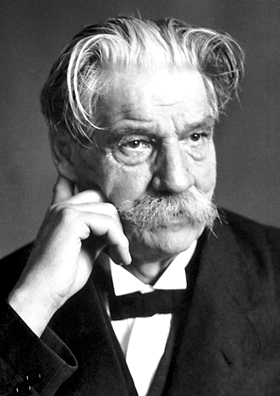

As you no doubt recall, scholars frequently divide the quest for the historical Jesus into phases or periods. The first period, following Albert Schweitzer‘s analysis, began with Hermann Samuel Reimarus and ended with William Wrede and Schweitzer himself. Conventional wisdom holds that the quest took a breather at that point, with scholars somewhat shell-shocked by the implications of the works by Wrede, Schweitzer, and Karl Ludwig Schmidt.

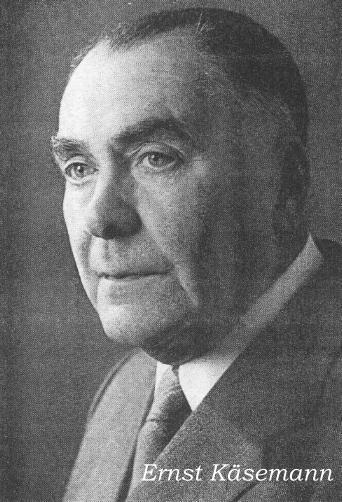

This same conventional wisdom marks the beginning of the “Second Quest” (or, at the time, “New Quest”) in the early 1950s with Ernst Käsemann’s lecture, “The Problem of the Historical Jesus” (published in Essays on the New Testament). The supposed hiatus between Schweitzer and Käsemann is sometimes called the period of “No Quest.”

Miffed scholars

Recently, just out of curiosity, I was Googling “no quest”, and I found several references to indignant conservative and not-so-conservative biblical scholars. They just don’t like that term. It’s dishonest, they insist, and if it’s one thing they can’t stand, it’s dishonesty.

Are they right? And if the pause or moratorium in the first half of the 20th century is a myth, then where did the idea come from and why does it persist?

A “No Quest” period?

First of all, here’s the typical description we get from survey courses and books on the Quest. The front matter for the Fortress Press “First Complete Edition” of The Quest of the Historical Jesus contains Marcus Borg’s “An Appreciation of Albert Schweitzer,” which ends with the following paragraph:

[Schweitzer’s] claim that historical Jesus scholarship has no theological significance has been very influential, contributing to a relative lack of scholarly interest in the historical Jesus for a major portion of this [i.e., the 20th] century. His work was thus not only the highwater mark of the “old quest” for the historical Jesus, but brought the quest to a temporary close. Only in the past few decades — with the “new quest” of the 1950s and 1960s and the “third quest” of the 1980s — has substantial interest in the historical Jesus revived. (Quest, p. ix, emphasis mine)

Gerd Theissen and Annette Merz (The Historical Jesus, A Comprehensive Guide) divide the quest into five phases in which two phases comprise the First Quest. Hence for them “No Quest” is the Third Phase, which they describe as “the collapse of the quest of the historical Jesus.” (Theissen and Merz, p. 9)

“Just not true”

Next, here’s a response from an offended, “anti-no-quest” scholar. In his essay, “The Secularizing of the Historical Jesus” (link downloads the PDF), Dale Allison complains about N.T. Wright’s characterization of the first half of the last century as experiencing a “moratorium” on the quest: