This is the second of two articles by Professor of Religion Sarah Iles Johnston. (The first article was addressed in Why Certain Kinds of Myths Are So Easy to Believe) I have been led to Johnston’s articles and books (along with other works addressing related themes by classicists) as I was led down various detours while reviewing M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths. I expect interested readers will see the relevance of Johnston’s thesis to Christian myths in the gospels and understand more deeply the mechanics at work that make them so believable for so many people.

Many Greek mythical narratives (whether poetry, drama or prose) appear to have no necessary relationship with a particular festival or other special occasion. They appear to have a life of their own and can be recited in quite different contexts and often with variations of details and even basic storylines. Variations, hearing only parts of a story that must be somehow fitted with a larger narrative, but with some difficulty because of certain differences of character or details, such presentations of the myths had the potential to arouse intense curiosity and discussion, with individuals surely acquiring their own understanding, view and relationship with a god or hero.

Who would ever imagine any similarity between Socrates and the Homeric hero Achilles? Johnston does not raise this illustration but it is one that illustrates her point well. Plato informs us that Socrates compared himself with Achilles. The philosopher with the warrior? Yes, because Socrates could explain to his audience that like Achilles, he likewise heroically followed what he believed to be the right or pious course of life even knowing it would result in his premature death. Variations in narratives encouraged deeper reflection and personal relationships with what the gods and heroes represented.

As Johnston points out, Greek myths generally were not point by point analogies to the real world but were metaphorical tales that were subject to reinterpretation and different functions or applications. The myth of Persephone, as we saw in the previous post, served equally well for a celebration of the hope for a good harvest and hope for a happier afterlife for initiates into the mysteries.

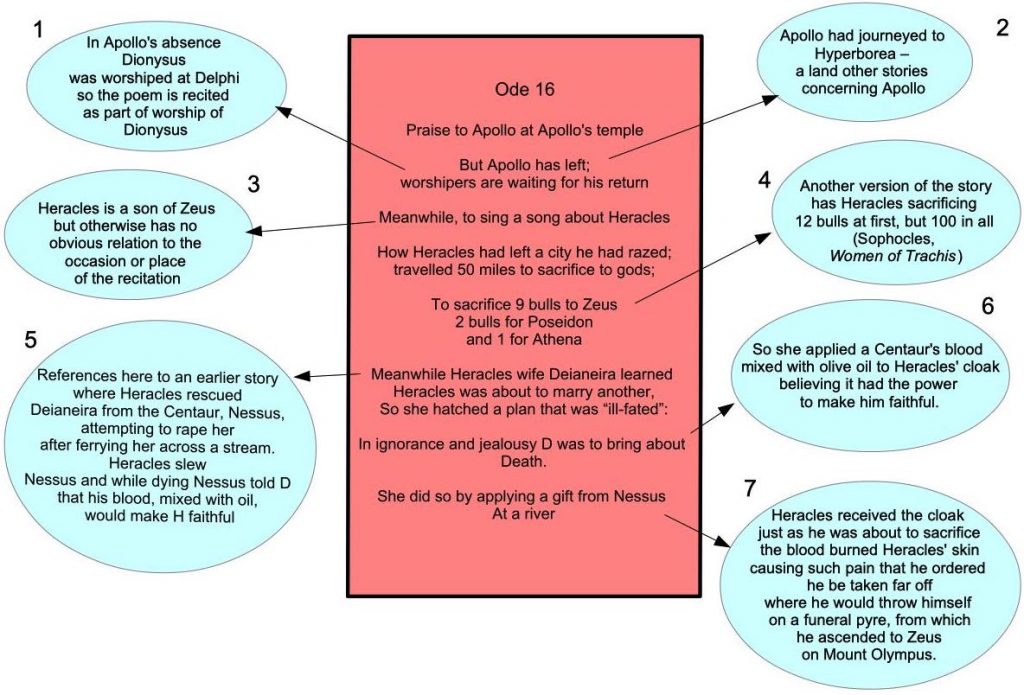

There is a poem by a fifth-century BCE poet, Bacchylides, that offers us another instance such devices that encouraged curiosity and engagement with the myths. In the centre I outline the thought-flow of the poem (in paraphrase) and beside it I have circled all the points that the poem in references in the wider world of Greek myth. Notice how much detail is left to the audience’s imagination, how many questions are potentially raised among those who are perhaps not fully acquainted with all of the associations or who are aware of differences with other accounts, or what questions of character arise when set in the wider mythical world. And why is Heracles being honoured at a festival in honour of Dionysus anyway? The Greeks evidently did not find any strong need to bind each story to a specific or analogous occasion (Johnston). The conclusion is surely designed to provoke much thought and discussion about the death of Heracles and his relations with his first wife, and the role of the Centaur.

One detail not brought out in the following diagram is that several of the related myths are linked to familiar places in the Greek peninsula: the city Heracles razed was in Eritrea, the place where he offered to Zeus was Cape Lithada, for example.

Click on the diagram if it does not appear in full in normal Vridar page setting.

The point of the above? Johnston explains:

The point of the above? Johnston explains:

. . . . the Greeks cared less about always making tightly logical connections between festivals and myths than we have imagined—or to put it otherwise, that the contributions that mythic narratives made to creating and sustaining belief in the gods and heroes could be more broadly based than we have previously acknowledged. More specifically, I suggest that an essential element that enabled this breadth of applicability was the tightly woven story world that was cumulatively being created on a continuous basis by the myths that were narrated. The closely intertwined nature of this story world validated not only each individual myth that comprised it but all the stories about what had happened in the mythic past, the characters who inhabited them, and the entire worldview upon which they rested. Because it was embedded in this story world, a skillfully narrated myth about Heracles, for example, had the power to sustain and enhance belief not only in Heracles himself but in the entire cadre of the divine world of which he was a member, including those divinities to whom the festival at which the myth was performed was dedicated.

(Johnston, Greek Mythic Story World, 284)

It should be kept in mind that these myths were often performed publicly, at temples and festivals in honour of certain gods.

The audiences were primed by these conditions to open their minds to the ideas that the myths conveyed, and thus the two, festival and myth, mutually supported one another.

So what is it that “makes story worlds in general coherent and credible”, Johnston asks.

Story Worlds

According to J.R.R. Tolkien there is the Primary World, the world in which we live, and then there is a Secondary World, one that an author creates and into which a reader enters — through “willing suspension of disbelief” (Coleridge?)? through “willing activation of pretense” (Saler)?, or, as Johnston prefers,

truly well-constructed story world requires no conscious decision at all on the part of audience members who participate in it — neither the suspension of disbelief nor the activation of pretense. It immerses readers or viewers so completely, yet so subtly, that they pass into it without even noticing that they are doing so.

(286)

A Secondary World needs to have a fence, a partition of some sort to separate it from our quotidian Primary World (Wolf). Dividing walls include wardrobe doors, rabbit holes, deserts traversed by houses carried in cyclones, interdimensional travel technology. Secondary Worlds are very different from Primary Worlds by virtue of strange inhabitants, strange landscapes, strange technology, and so forth. Greek myths are not exactly like that, nor are the gospels or other biblical stories. Yes, they do contain monsters, talking snakes and donkeys, but these oddities are placed in “our world”, a “real world”, the Primary World in which we all exist. They are the oddities in our “real” world; in Greek myths and biblical stories we have not, as a rule, entered worlds that are entirely strange in every way. (There are a few exceptions such as when Odysseus is on an island with a witch who changes his crew into wild beasts but such stories are set in a larger more recognizable world — with normal geographical, botanical and zoological features.)

Even when a monster does enter a Greek myth the author tends to indicate only minimal interest in its oddities. They are described as if in passing. The story is set in “a real-world” that we recognize as our own, or as the Greeks recognized as theirs:

Consider this passage from the Iliad in which the story of Bellerophon and the Chimaera is told (Il. 6.171–83):

So off went Bellerophon to Lycia, under the excellent escort of the gods. And when he reached the river Xanthus, the king welcomed him and honored him with entertainment for nine solid days, killing an ox each day. But when the tenth dawn spread her rosy light, the king questioned him and asked to see the tokens that his son-in-law Proetus had sent. And when he saw the evil tokens, he ordered Bellerophon to kill the furious Chimaera, a creature that was not human but divine; a lion in front, a serpent in the rear, and a goat in the middle, and breathing fire. Bellerophon killed her, trusting in signs from the gods. (trans. Lombardo, slightly modifi ed).

Homer does not fail to mention the Chimaera’s triple physiognomy and fiery breath, but he does not take full advantage of their narrative possibilities . . . . In this and many other cases, moreover, that which is marvelous is situated squarely within familiar activities or against a familiar backdrop: Bellerophon departs to fight the Chimaera after a series of feasts such as Homeric kings typically serve to important visitors; in Pindar’s narration of Jason’s exploits on Colchis, the sheer physical strength that the hero displays while yoking Aeetes’ oxen and guiding their plow merits more attention than the oxen’s fiery breath and brazen hooves (P. 4.232–38). Similarly, Theseus’s visit to the marvelous undersea palace of Poseidon and Amphitrite, as narrated by Bacchylides in his seventeenth dithyramb, is well integrated into an eventful but otherwise realistic voyage across the Aegean.

(289)

Readers who have been following my series on M. David Litwa’s book, How the Gospels Became History, will hear a distinct echo here.

A story world can be entirely imaginative yet still a step back from a fantasy Secondary World. Novelists can set stories in real places or in imaginative locations that are based on real cities, real streets, real neighbourhoods and people. They are like the Primary World.

There are, furthermore, stories that are very like the Primary World but manage to incorporate a monster, like Dracula, for instance. The point here is that one or very few fantastical elements do not of themselves create a Secondary World of fantasy. A Secondary World is different in a host of ways from the Primary one. The world in which a single monster appears may be set in a world very much like reality, so that rather than leading readers to think, That’s ridiculous!, they lead them to imagine an “expansion of the narrative world’s possibilities.”

Yet overall, the monstrous and the marvelous are treated with relative restraint by ancient authors. The effect is much like that produced in the modern genre of magic realism, where elements that, in isolation from their narratives, might stand out as magical or fantastic — ghosts conversing with the living, telepathy, and extraordinary longevity, for instance — are integrated into the everyday world in such a way as to be accepted by audience members unhesitatingly. This does not rob them of their marvelousness; rather, it enables them to contribute to an expansion of the narrative world’s possibilities.

(290)

To digress once more, one is reminded of apologists’ stress on the “simplicity” with which Jesus’ miracles are narrated, drawing attention to how “realistic” they are. It is not just their simplicity, however, if we are following Johnston’s thesis, it is that they are embedded so completely in a “real world”, the Primary World.

My initial conclusions, then, are that the story world of Greek myths is not a strongly secondary one, that the secondary qualities that it does possess focus upon single, circumscribed events or characters, and that those events or characters are often integrated into descriptions of the Primary World in such a way as to expand possibilities within the latter rather than highlight the extraordinariness of the former.

(290)

When Greek authors did spread their wings and launch into tales of the fantastic (e.g. Lucian’s True History) contemporaries recognized them as genuinely “not of this world”, not real, but fantasy, even satire. Normally mythical tales were mapped on to the real world and real places known to audiences.

But is that how you feel in your bones?

But is that how you feel in your bones?

Johnston anticipates doubts. Surely when we reflect on the Greek myths we know we tend to imagine a distinctive world alien to the historical one.

Nonetheless, I suspect that many of us feel in our bones that Greek myths do, collectively, have a distinct story world. One reason for this is that we grew up surrounded by books that corral individual myths into anthologies. Translated or re-narrated by the voice of a single author, illustrated by the pen or brush of a single artist, and then bound between two covers, the myths are perforce given cohesiveness. The practice has a long history: Ovid and Apollodorus were already doing it, as were predecessors such as Pherecydes and Hellanicus. Centuries of European art cemented the idea, not only insofar as the artists took particular pleasure in illustrating Ovid, the greatest of all unifiers, but also insofar as there was a tacit agreement that Greek myths — virtually any Greek myths, whether they came through Ovid or not — were among the few appropriate subjects for upper-class décor. Walking today through a museum gallery in which such works have been gathered together is like strolling through a mythographic handbook.

(292)

The Mythic Network

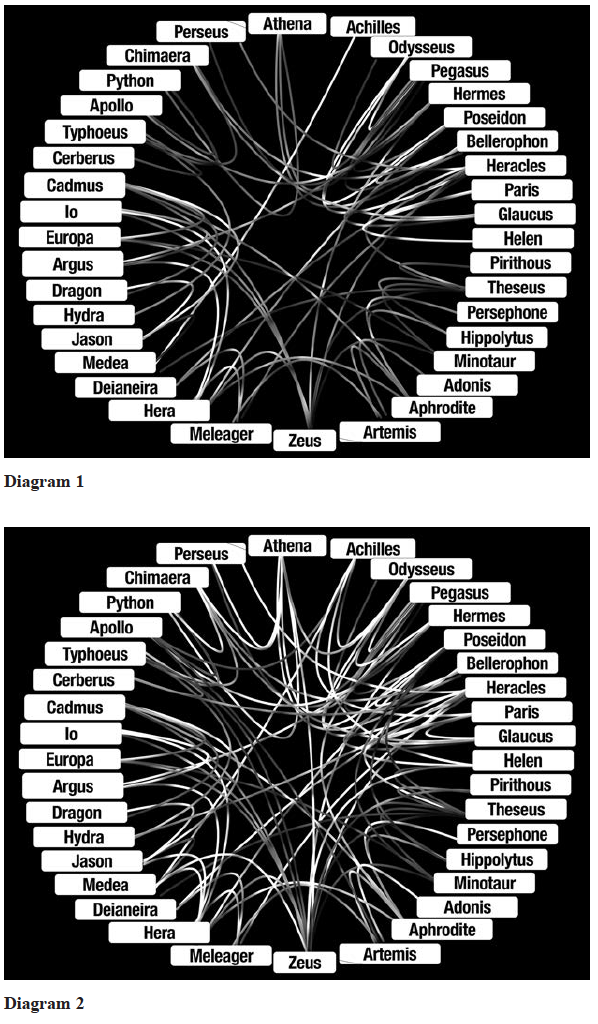

Here is another feature of Greek myths that contributes towards their story world. The gods, the heroes and the monsters that appear in any one story are always part of a vast network. See again the diagram of Bacchylides’ Ode 16 to Heracles above. There are no stand-alones in Greek myths. Even the python slain by Apollo is linked to a world of other monsters. One illustration:

The monstrous Python may have been new to some people the first time they heard the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, but the narrator ties her into the larger family of mythic monsters by mentioning that

- the Python had been the nursemaid of Typhoeus, a dreadful creature about whom Hesiod had a lot to say.

- And the narrator makes Apollo himself tell us a few lines later that the Python was a pal of the Chimaera, who first appeared in the Iliad

- and whom Hesiod said was the child of Typhoeus (as were Cerberus and the Hydra).

(293, my formatting)

Gods, heroes, monsters, — each story involved characters who were connected with other characters in other stories and events were connected with other events in other myths, sometimes the links being traditional, sometimes a poet perhaps inventing them — everyone was connected in some way, if not always consistently.

Those who wished to create new myths, moreover, understood the importance of tying their threads securely into the familiar, existing tapestry . . . .

But when embedded in myths, the relationships not only come to life but help to create a coherent story world that serves to anchor and validate each individual myth in an infinitely reciprocal way. That is, effective narration of Theseus’s adventure with the Minotaur also lends credibility to Perseus’s defeat of Medusa or to the birth of Erichthonius as a creature half-snake and half-human, because all of these figures are presented as inhabiting the same realm — a realm that is thickly crisscrossed by the relationships that I have been talking about. Each story stands as a guarantor of the existential rules underlying the others and is, in turn, guaranteed by them. Each of them contributes to a completely furnished world from which audience members may subsequently break off pieces to use as a situation demands — pieces that still refract the authority and allure of the whole (cf. Eco 1985.198). This is one reason that figures and incidents from myths are so powerful as symbols: even when we regard them singly, they are never actually alone.

In a sense, what I am describing is a sort of hyperseriality: an extended version of the seriality common to Greek myths that I described in my earlier article.

(296 f)

As we saw in the previous post, the seriality of the myths becomes as compelling as the serial adventures of soap operas today, or as the early novels of Dickens and Hardy. Characters who are central heroes in one narrative can appear in another as support figures, perhaps only for one or two scenes.

characters fade in and out of one another’s stories in a manner that begins to dissolve any single story into something much larger. (299)

(I suggest that we see similar networks in the way the gospel narratives are tied so closely by a variety of mechanisms to the stories and characters of the “Old Testament”.)

I want to highlight, once more, the dense intertwining of characters and their stories in these sorts of narratives and the difficulty of completely disengaging anyone of them from the much larger network of which they are a part. . . . I want to emphasize that the Greek mythic hyperserial, like all hyperserials, constitutes a network that stretches in many directions at once, thickly intertwining its participants with one another. Were we to diagram all of the relationships that I mentioned in the first three paragraphs with which Section 3 began, representing each relationship as a line between the two characters involved, we would end up with a diagram like the first one that I provide: the lines cross thickly. Were I to add lines representing just some of the other relationships amongst these characters that could not be easily inserted into my linear narrative (e.g., Odysseus received moly from Hermes, Poseidon sent the bull that frightened Hippolytus’s horses, Apollo and Artemis were twins, Paris killed Achilles), the lines would cross more thickly still.

(300)

Crossovers

When I first read Apollonius’s Argonautica (the story of Jason’s quest for the golden fleece) I was thrown back for a while trying to grasp how it was that so many major mythical figures from widely diverse stories were all coming together in this epic. I was not expecting to see Heracles, for instance, among Jason’s crew. Happily, in the course of the journey, he did find a reason to leave the crew behind and no doubt was thus free to encounter is “traditional” adventures. So I found Johnston’s discussion of this phenomenon of particular interest:

The surprise of meeting a familiar character where we don’t expect to generates an additional level of interest in the story. . . . Crossovers may also reward audience members with a sense of having special knowledge that makes them feel complicit with the narrator and thus further encourages them to buy into the narrative . . . .

But crossovers frequently serve another important purpose: by evoking a story world that is already familiar and accepted, a crossover is a powerful way of giving verisimilitude to a new tale and its characters. . . . Some times a crossover confirms or reorients a character by bringing him or her into contact with one or more characters who are already well established.

(302)

Again, to digress: do we not see a similar operation with the introduction of Moses and Elijah at the Transfiguration of Jesus? Or Noah’s dove at the baptism of Jesus?

Again, to digress: do we not see a similar operation with the introduction of Moses and Elijah at the Transfiguration of Jesus? Or Noah’s dove at the baptism of Jesus?

Crossovers, to sum up, can do a number of things very efficiently: establish the existential, ethical, and operational rules of a new story, lend it credibility and authority by their mere presence, and establish a particular climate or mood by gesturing towards other myths. . . . . Both stories, in other words, implicitly claim to reveal “how it all came about” — a perennial object of human curiosity. . . .

Everything can be made to fit together; everything can be understood as part of a single, bigger picture and thus ratifi ed, if only you know where to look for the missing pieces — or how to fashion them yourself.

(305 f)

In other words, it’s kind of like a set of citations, a way to add authority to an article. (See the letter to Howard dated August 14, 1930, at http://www.hplovecraft.com/creation/necron/letters.aspx — Johnston’s citation.)

The Story World of Greek Myth

Myth is a different genre from fantasy. A Secondary World is made up of characters and paraphernalia that society does not intend readers to believe are real. Myths, on the other hand, even though containing gods, heroes and monsters, take place in a world that “looked very much like the Primary World”. Myths encouraged the belief that gods and heroes continued to exist in “our world”. We saw in recent posts that there is no sharp dividing line between a remote mythical heroic age and the world of recent history and contemporary concerns: gods and heroes have continued to appear and act in the Primary World.

- Greek Gods and Heroes Active in the Historical World

- Greek Gods and Heroes with Multiple Historical Eyewitnesses

- Miracles with Multiple Jewish and Roman Eyewitnesses

- Ancient Belief that Divinities Appeared on Earth in the Present and Historical Past — (with half a glance at Christian origins)

- Ancient Epiphanies and a Comparison with Christian Counterparts

Johnston’s explanations appear to concur:

The myths’ representations of gods, heroes, and monsters existing in a world that looked very much like the Primary World is a reflection of two things:

a belief that the gods and heroes continued to exist in, and to affect, the world in which those myths were being narrated (a belief that was sustained by the ways in which the myths were narrated, as I explore in my first article),

and the Greek understanding that . . . the things, people, and events of an earlier age during which the actions of the myths were set . . . had melted into those of the present age without an abrupt change.

There was no single moment at which the mythic world decisively changed into the world that we know today, and, therefore, the deeds described by the myths existed on a continuum that flowed uninterruptedly into the time of the listeners.

(307, my formatting)

So Greeks might be frequently noticing beaches, streams, caves, mountains, that were locations of actions by heroes and gods, and they were definitely reminded of those “mythic” persons and events by the monuments and landmarks throughout their cities. The geographer Pausanias documented the many mythical tales that were associated with the places he described.

According to such a view, although it might not be reasonable to expect to encounter more nine-headed snakes in Lerna or three-bodied monsters in Spain (the passage of time was understood to have changed some things, after all; while they still dwelt on earth, Heracles and the other heroes had cleared the land of such creatures), or to expect gods to transmogrify people into new animals and plants (the natural world had been holding steady for some centuries), it would be reasonable to expect the heroes and the gods to remain an active part of the contemporary world.

(308)

And so we come full circle. It was at this point, after reading the above, that I began my series of accounts of gods and heroes turning up and acting with historical and contemporary witnesses, a series that had been sparked by Johnston’s article.

When I resume discussing Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History I expect to refer back to these posts.

Johnston, Sarah. 2015. “The Greek Mythic Story World.” Arethusa 48 (3): 283–311. https://doi.org/10.1353/are.2015.0008.

The following article was the basis of the previous post:

Johnston, Sarah Iles. 2015. “Narrating Myths: Story and Belief in Ancient Greece.” Arethusa 48 (2): 173–218. https://doi.org/10.1353/are.2015.0011.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- No Evidence Cyrus allowed the Jews to Return - 2024-04-22 03:59:17 GMT+0000

- Comparing Samaria and Judah/Yehud – and their religion – in Persian Times - 2024-04-20 07:15:59 GMT+0000

- Samaria in the Persian Period - 2024-04-15 11:49:57 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

One thought on “How Mythic Story Worlds Become Believable (Johnston: The Greek Mythic Story World)”