When I hear of how Russia “attacked” the USA in the 2016 elections, and when I hear of verbal abuse being labeled a form of “violence”, and when I think a purple dot is blue because fewer blue dots have been appearing lately, then I think of “concept creep”. And then I recall how many of those of us leaving cults or other extreme fundamentalist churches were said to be experiencing the same disorder as returning soldiers with war experiences, “post traumatic stress disorder”.

Concepts that refer to the negative aspects of human experience and behavior have expanded their meanings so that they now encompass a much broader range of phenomena than before. This expansion takes “horizontal” and “vertical” forms: concepts extend outward to capture qualitatively new phenomena and downward to capture quantitatively less extreme phenomena. The concepts of abuse, bullying, trauma, mental disorder, addiction, and prejudice are examined to illustrate these historical changes. In each case, the concept’s boundary has stretched and its meaning has dilated. A variety of explanations for this pattern of “concept creep” are considered and its implications are explored. I contend that the expansion primarily reflects an ever-increasing sensitivity to harm, reflecting a liberal moral agenda. Its implications are ambivalent, however. Although conceptual change is inevitable and often well motivated, concept creep runs the risk of pathologizing everyday experience and encouraging a sense of virtuous but impotent victimhood.

- Haslam, Nick. 2016. “Concept Creep: Psychology’s Expanding Concepts of Harm and Pathology.” Psychological Inquiry 27 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2016.1082418.

—

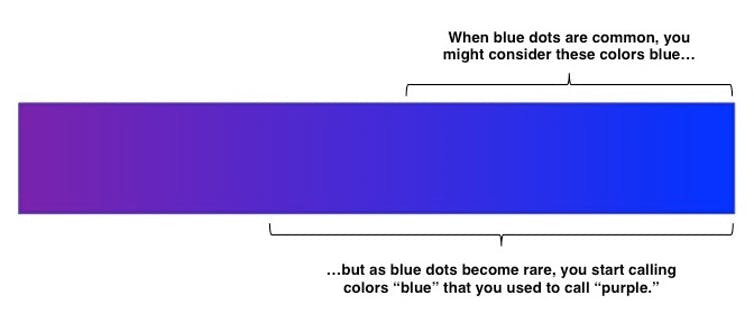

Why do some social problems seem so intractable? In a series of experiments, we show that people often respond to decreases in the prevalence of a stimulus by expanding their concept of it. When blue dots became rare, participants began to see purple dots as blue; when threatening faces became rare, participants began to see neutral faces as threatening; and when unethical requests became rare, participants began to see innocuous requests as unethical. This “prevalence-induced concept change” occurred even when participants were forewarned about it and even when they were instructed and paid to resist it. Social problems may seem intractable in part because reductions in their prevalence lead people to see more of them.

- Levari, David E., Daniel T. Gilbert, Timothy D. Wilson, Beau Sievers, David M. Amodio, and Thalia Wheatley. 2018. “Prevalence-Induced Concept Change in Human Judgment.” Science 360 (6396): 1465–67. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap8731.

—

Looking for trouble

To study how concepts change when they become less common, we brought volunteers into our laboratory and gave them a simple task – to look at a series of computer-generated faces and decide which ones seem “threatening.” The faces had been carefully designed by researchers to range from very intimidating to very harmless.

As we showed people fewer and fewer threatening faces over time, we found that they expanded their definition of “threatening” to include a wider range of faces. In other words, when they ran out of threatening faces to find, they started calling faces threatening that they used to call harmless. Rather than being a consistent category, what people considered “threats” depended on how many threats they had seen lately.

- Levari, David. n.d. “Why Your Brain Never Runs out of Problems to Find.” The Conversation. Accessed July 26, 2018. http://theconversation.com/why-your-brain-never-runs-out-of-problems-to-find-98990.

“Expanding one’s definition of a problem may be seen by some as evidence of political correctness run amuck,” Gilbert said. “They will argue that reducing the prevalence of discrimination, for example, will simply cause us to start calling more behaviors discriminatory. Others will see the expansion of concepts as an increase in social sensitivity, as we become aware of problems that we previously failed to recognize.”

“Our studies take no position on this,” he added. “There are clearly times in life when our definitions should be held constant, and there are clearly times when they should be expanded. Our experiments simply show that when we are in the former circumstance, we often act as though we are in the latter.”

- “‘Prevalence Induced Concept Change’ Causes People to Re-Define Problems as They Are Reduced, Study Says.” n.d. Accessed July 26, 2018. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2018-06-prevalence-concept-people-re-define-problems.html.

I position concept creep within the recent historical trend of rising political polarization, particularly “affective partisan polarization,” which refers to the increasing hostility felt by partisans toward people on the other side. I tell this story in three graphs. Together, the trends in these graphs can explain why concepts of trauma and victimhood have undergone such rapid expansion on university campuses and among psychologists. In brief, the loss of political diversity in many universities–and in psychology in particular–at a time of rising cross-partisan hostility has amplified the already powerful process of motivated reasoning. Concepts are morphing to become ever more useful to “intuitive prosecutors” (Tetlock, 2002) who are prosecuting their enemies in the culture war.

- Haidt, Jonathan. 2015. “Why Concepts Creep to the Left.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2702523. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2702523.

—I am not claiming that this is necessarily a bad thing. Indeed, I believe there is much good that has come from these concepts receiving attention. Indeed, the societal changes associated with each of the six concepts that Haslam reviews require their own analysis in terms of harms and benefits. However, thanks to Halsam’s work, we can now reflect on some of the implications of concept creep in general.

- Henriques, Gregg. n.d. “The Concept of Concept Creep.” Psychology Today. Accessed July 26, 2018. https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/theory-knowledge/201701/the-concept-concept-creep.

Benson, Ophelia. 2018. “More Blue Dots – Butterflies and Wheels.” July 24, 2018. http://www.butterfliesandwheels.org/2018/more-blue-dots/.<

Burkeman, Oliver. 2018. “Are Things Getting Worse – or Does It Just Feel That Way? | Oliver Burkeman.” The Guardian, July 20, 2018, sec. Life and style. http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/jul/20/things-getting-worse-or-feel-that-way.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- No Evidence Cyrus allowed the Jews to Return - 2024-04-22 03:59:17 GMT+0000

- Comparing Samaria and Judah/Yehud – and their religion – in Persian Times - 2024-04-20 07:15:59 GMT+0000

- Samaria in the Persian Period - 2024-04-15 11:49:57 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Psychological violence can be just as harmful as physical violence. Human history is an ugly spectacle of intolerance and cruelty, often masked as normal. We have made progress in some respects. Public torture and executions are no longer viewed as public entertainment in most places. Slavery has been outlawed. Women and minorities are accorded more rights than in the past. At long last, homosexuals are regarded as human.

Whatever the underlying causes of this progress, a sense of moral outrage has been a primary tool in combating cruelty and injustice. But much cruelty and injustice remain and there is still ample reason for moral outrage. Because we no longer enjoy watching other humans being skinned alive, or being choked on their own entrails, is no reason to dismiss our condemnation of taking children from their parents as “concept creep”. Public intellectuals do not serve the cause of civilization or humanity by dismissing the efforts of “snowflakes” to address more subtle forms if discrimination and injustice. You are fortunate that you were not traumatized by your cult experience, but that doesn’t give you license to dismiss the suffering of those who have been.

The really disturbing “concept creep” that we are experiencing today is the accommodation of large numbers of people to escalating acts of cruelty. Separating babies from their parents is justified by saying that if the parents cared about their babies they wouldn’t bring them here. Germans were hardened to accept the murder of six million people by the gradual exposure to thousands of acts of cruelty. To be worrying about “creeping” sensitivity to cruelty in an age of creeping insensitivity to cruelty is perverse and ominous.

If we are fighting over what our expert definitions are and what qualifies as suffering or injustice, I think we are in a good place. Those blue dots that are now mostly missing represented things like slavery and packing people into boxcars. Isn’t this a sign of human progress?

Haidt, Jonathan. 2015. “Why Concepts Creep to the Left.”

What does this even mean, given that the concept of “Left” has itself changed?

There’s a lot of talk about the ‘Overton Window’ which in American politics seems to be tracking rightward, thus creating a situation where opinion leaders are calling mainstream ideas like universal healthcare and education ‘extreme leftist’ proposals.