Continuing from Chap 3c . . . .

The Exodus: Metaphor Preceded “History”

Other examples of changing names and wordplay:

The narrative can even culminate in the bestowing of a new name, or make the point that the change of name is itself the central point, along with all that it signifies:

Isaiah 62:1-4

for Jerusalem’s sake I will not remain quiet,

. . . .

you will be called by a new name

that the mouth of the Lord will bestow.

. . . .

No longer will they call you Deserted,

or name your land Desolate.

But you will be called Hephzibah [=My Delight is in Her]

and your land Beulah [=Married]

As mentioned earlier, Philo found much of interest in the names assigned to biblical characters, especially when names were changed. Noteworthy was the pattern of the three patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (Israel), and the fact that the first and third had name-changes but that the middle one, Isaac, remained Isaac throughout. This was seen by Philo to point to Isaac being the central character to which we all must aspire. Abram to Abraham and Jacob to Israel — these figures were “becoming”, progressing; Isaac represented a timeless ideal for all.

Recall from earlier posts Charbonnel’s discussion of assonance as part of the word-play that moulded the meaning of the narrative. Further examples:

Jeremiah 1:11-12

11 The word of the Lord came to me: “What do you see, Jeremiah?”

“I see the branch of an almond tree [שָׁקֵ֖ד] =šā·qêḏ],” I replied.

12 The Lord said to me, “You have seen correctly, for I am watching [שֹׁקֵ֥ד = šō·qêḏ] to see that my word is fulfilled.”

Amos 8:1-2

Thus hath the Lord God shown unto me: And behold, a basket of summer fruit [קָ֑יִץ = qā·yiṣ].

2 And He said, “Amos, what seest thou?” And I said, “A basket of summer fruit.” Then said the Lord unto me: “The end [הַקֵּץ֙ = haq·qêṣ] is come upon My people of Israel; I will not again pass by them any more.

Another instance where narratives resonate through the level of text predominating over literal meaning is found in a comparison of Noah and Moses. Noah was saved in an ark, a very large boat — תֵּבַ֣ת / tê·ḇaṯ; Moses was saved in a basket lowered into the Nile — תֵּבַ֣ת / tê·ḇaṯ. Comment by Marc-Alain Ouaknin in Mystères de la Bible,

Noah and Moses were not saved because they were protected by a boat, but because they entered into the universe of language, they were protected by the same word. (A wild and woolly paraphrase. I do not have access to Ouaknin’s book.)

Let’s look at another case. See here how the language of military conquest and release becomes the history of an Exodus from Egypt. NC cites passages from Mario Liverani’s Israel’s History and the History of Israel, though she does so from the French publication. I quote sections from the English-language text, pp. 277-279 in which he shows how an image of exodus from a foreign kingdom was a common metaphor before our well-known Pentateuchal story was composed. Liverani uses the traditional eighth-century dating of the early prophets.

The Exodus Motif

. . . The sagas of the ‘patriarchs’ offered an inadequate legitimation, because they were too remote and were localized only in a few symbolic places (tombs, sacred trees). A much more powerful prototype of the conquest of the land was created by the story of exodus (sē’t, and other forms of yāsā’ ‘go out’) from Egypt, under the guidance of Moses, and of military conquest, under the leadership of Joshua.

The main idea of the sequence ‘exit from Egypt –> conquest of Canaan’ is relatively old: already before the formulation of the Deuteronomistic paradigm, the idea that Yahweh had brought Israel out from Egypt is attested in prophetic texts of the eighth century (Hosea and Amos). In Amos the formulation has a clearly migratory sense:

Did I not bring Israel up from the land of Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor and the Arameans from Kir? (Amos 9.7).

In Hosea, the exit from Egypt and return there are used instead as a metaphor (underlined by reiterated parallelism) for Assyria, in the sense of submission or liberation from imperial authority. Because of its political behaviour, and also for its cultic faults, Ephraim (= Israel, the Northern Kingdom, where Hosea issues his prophecies) risks going back to ‘Egypt’, which is now actualized as Assyria:

Ephraim has become like a dove

silly and without sense;

they call upon Egypt, they go to Assyria (Hos. 7.11).Though they offer choice sacrifices

though they eat flesh,

Yahweh does not accept them.Now he will remember their iniquity,

and punish their sins;

they shall return to Egypt (Hos. 8.13; see 11.5).They shall not remain in the land Yahweh;

but Ephraim shall return to Egypt,

and in Assyria they shall eat unclean food (Hos. 9.3).Ephraim…they make a treaty with Assyria,

and oil is carried to Egypt (Hos. 12.2 [ET 1]).In these eighth-century formulations, the motif of arrival from Egypt was therefore quite well known, but especially as a metaphor of liberation from a foreign power. The basic idea was that Yahweh had delivered Israel from Egyptian power and had given them control – with full autonomy – of the land where they already lived. There was an agreed ‘memory’ of the major political phenomenon that had marked the transition from submission to Egypt in the Late Bronze Age to autonomy in Iron Age I.

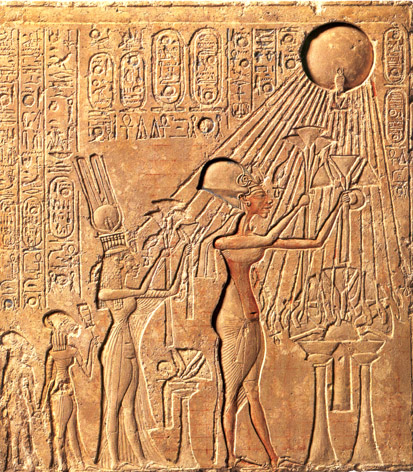

We should bear in mind that the terminology of ‘bringing out’ and ‘bringing back’, ‘sending out’ and ‘sending in’, the so-called ‘code of movement’, so evident in Hosea, had already been applied in the Late Bronze Age texts to indicate a shifting of sovereignty, without implying any physical displacement of the people concerned, but only a shift of the political border. Thus, to take one example, the Hittite king Shuppiluliuma describes his conquest of central Syria in the following way:

I also brought the city of Qatna, together with its belongings and possessions, to Hatti… I plundered all of these lands in one year and brought them [literally: ‘I made them enter’] to Hatti (HDT 39-40; cf. ANET, 318).

And here is another example, from an Amarna letter:

All the (rebellious) towns that I have mentioned to my Lord, my Lord knows if they went back! From the day of the departure of the troops of the king my Lord, they have all become hostile (EA 169, from Byblos).

Egyptian texts also describe territorial conquest in terms of the capture of its population, even if in fact the submitted people remain in their place. This is an idiomatic use of the code of movement (go in/go out) to describe a change in political dependence.

But when, towards the end of the eighth century, the Assyrian policy of deportation began (with the physical, migratory displacement of subdued peoples), then the (metaphorical) exodus from Egypt was read in parallel with the (real) movement from Israel of groups of refuges from the north to the kingdom of Judah (Hos. 11.11). The inevitable ambiguity of the metaphor of movement gave way to a ‘going out’ which was unambiguously migratory, though it maintained its moral-political sense of ‘liberation from oppression’. The first appearance of this motif occurs, significantly, in the Northern kingdom under Assyrian domination.

Thus in the seventh century the so-called exodus motif took shape in proto-Deuteronomistic historiography. The expression ‘I (= Yahweh) brought you out from Egypt to let you dwell in this land that I gave to you’ (and similar expressions) became frequent, as if alluding to a well known concept. Evidently this motif, influenced by the new climate of Assyrian cross-deportations, and the sight of whole populations moving from one territory to another, was now connected to the patriarchal stories of pastoral transhumance between Sinai and the Nile Delta, to stories of forced labour of groups of habiru (‘pr.w) in the building activities of the Ramessides, and to the more recent movements of refugees between Judah and Egypt: such movement was therefore no longer understood as a metaphor, but as an allusion to an actual ‘founding’ event: a real ‘exodus’, literally from Egypt.

Just as in Hosea the Exodus motif already provided a metaphor for the Assyrian threat, so in prophetic texts of the exilic age the exodus became (more consistently) a prefiguration of the return from the Diaspora – at first, fleetingly, from the Assyrian, to a (still independent) Jerusalem; then firmly, from the Babylonian disapora:

Therefore, the days are surely coming, says Yahweh, when it shall no longer be said, ‘As Yahweh lives who brought the people of Israel up out of the land of Egypt,’ but ‘As Yahweh lives who brought out and led the offspring of the house of Israel out of the land of the north and out of all the lands where he had driven them.’ Then they shall live in their own land’ (Jer. 23.7- 8; 16.14-15).

(Liverani, 277 ff)