The chronological debate

In the case of canonical gospel chronologies, debate on the matter of Synoptic vs. Johannine has continued decade after decade with no apparent end in sight. Apologists, for whom clever harmonization is a virtue, have diligently tried to make all the pieces fit, using every well-known tool. Sadly, the plain meaning of the text will rarely survive the most ingenious attempts at harmonization.

When confronted with two bits of contradictory evidence, X and Y, we have four possibilities:

- X and Y are both true. (We simply need to explain away the “apparent” contradictions.)

- X is true, and Y is false.

- Y is true, and X is false.

- Neither X nor Y is true. (Or at least, not entirely true.)

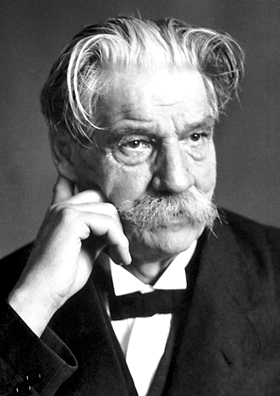

Schmidt surveyed the existing works on the subject, pointing out how champions of either chronology (Johannine or Synoptic) easily saw the discrepancies on the opposite side while blind to their own — mote vs. beam, so to speak. Ultimately, we can’t rely on any of the gospels when it comes to sequence or duration.

Harmonization

Those brave souls who tried to fit both chronologies into a single coherent timeline earned some measure of admiration in Schmidt’s eyes. Heaven knows they put forth a valiant effort. However, at some point, such scholars must argue for an interpolation here or there, or argue that the plain meaning of this or that verse actually meant something else. Or perhaps, as Hans Windisch would insist, some of the chapters must be out of order.

In our own day, we still see scholars arguing that Jesus cleansed the Jerusalem Temple early in his career (John) and then again during his last week on Earth (Synoptics). Maybe he did it several years in a row without ever getting arrested, because — well, why the hell not? If we step back and honestly evaluate the process of apologetic harmonization, we see that it is at least as corrosive as “skeptical” critical analysis. Why, we must finally ask ourselves, do we continually rework the evidence to fit an unchanging (and unchangeable) conclusion? At best, it is harmless busy work. At worst, it’s dishonest mental gymnastics. [I’m expressing my own thoughts here, not Schmidt’s, by the way.] Continue reading “K. L. Schmidt’s “Framework” Part 1: Introduction — Duration and Timeline”

While doing a little background research on folklore and oral tradition, I happened upon something written by

While doing a little background research on folklore and oral tradition, I happened upon something written by

Bart gets on a roll in

Bart gets on a roll in