[Updated 12 hours after original posting]

I’d like to place here some balance or corrective to Tim O’Neill’s criticism of Catherine Nixey’s The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World. James McGrath has lent his support to O’Neill’s attack on Nixey’s book by expressing disdain for both atheists and their “gullible” audiences:

When atheists misrepresent ancient Christians as typically having been intellectual terrorists who burned great works of literature and philosophy, are they not themselves doing the equivalent themselves, burning the actual history in the minds of those gullible enough to blindly accept their claims, in order to replace our accurate knowledge of the past with their own dishonest dogma and that alone?

Just this morning I see that another biblioblog has collated some “critical reactions” to Nixey’s book.

To begin, Catherine Nixey makes it clear in her Introduction that what readers are about to encounter is a one-sided polemic.

This is a book about the Christian destruction of the classical world. The Christian assault was not the only one – fire, flood, invasion and time itself all played their part – but this book focuses on Christianity’s assault in particular. This is not to say that the Church didn’t also preserve things: it did. But the story of Christianity’s good works in this period has been told again and again; such books proliferate in libraries and bookshops. The history and the sufferings of those whom Christianity defeated have not been. This book concentrates on them. (p. xxxv, my emphasis)

It seems to me a little awry to condemn an author’s work because it accomplishes what its author intended it to do. But it is more serious to give the impression that a book denies something that it clearly does not: Nixey clearly says that the Church did, also, “preserve things”. Are we to think that even in the twenty-first-century one cannot speak ill of Christian history without attracting an avalanche of hostility?

Nixey, I understand, is a journalist and is writing for a popular audience. Often she adds little imaginative (novelistic) flourishes to fill out a dramatic historical episode. The book is neither a textbook nor original research. Nixey relies heavily on secondary literature rather than original research. That said, much of her secondary sources are highly respected scholars in the field (e.g. Robert Wilken, Dirk Rohmann).

Where to begin? Let’s return to the passage quoted above. Note that Nixey does not speak of “Christians” or “Christianity” as if these terms are labels of a monolithic movement. Christians in late antiquity were divided. Yet some of the attacks (they are more attacks than fair criticisms) appear at times to speak erroneously of Christianity as a united voice with a single attitude towards pagan learning. O’Neill writes:

The idea that the loss of ancient works came as a result of active suppression by “Christian authorities” coupled with ignorant neglect is the persistent element in these laments. In her recent debut book The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World, British popular history writer Catherine Nixey harps on this theme. “Works by censured philosophers were forbidden,” she solemnly assures her readers, “and bonfires blazed across the empire as outlawed books went up in flames.” (p. xxxii) I imagine this kind of stuff sells popular books, but if we actually turn to the evidence and the relevant scholarship, we find very little to support these ideas.

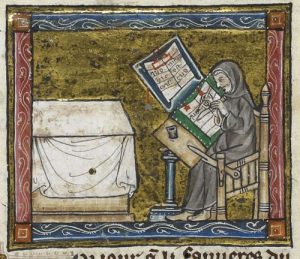

It is a powerful image, this: Christianity as the inheritor and valiant protector of the classical tradition – and it is an image that persists. This is the Christianity of ancient monastic libraries, of the beauty of illuminated manuscripts, of the Venerable Bede. It is the Christianity that built august Oxford colleges, their names a litany of learnedness – Corpus Christi, Jesus, Magdalen. This is the Christianity that stocked medieval libraries, created the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, the Hours of Jeanne de Navarre and the sumptuous gold illustrations of the Copenhagen Psalter. This is the religion that, inside the walls of the Vatican, even now keeps Latin going as a living language, translating such words as ‘computer’, ‘video game’ and ‘heavy metal’ into Latin, over a millennium after the language ought to have died a natural death.

It is a powerful image, this: Christianity as the inheritor and valiant protector of the classical tradition – and it is an image that persists. This is the Christianity of ancient monastic libraries, of the beauty of illuminated manuscripts, of the Venerable Bede. It is the Christianity that built august Oxford colleges, their names a litany of learnedness – Corpus Christi, Jesus, Magdalen. This is the Christianity that stocked medieval libraries, created the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, the Hours of Jeanne de Navarre and the sumptuous gold illustrations of the Copenhagen Psalter. This is the religion that, inside the walls of the Vatican, even now keeps Latin going as a living language, translating such words as ‘computer’, ‘video game’ and ‘heavy metal’ into Latin, over a millennium after the language ought to have died a natural death.

And indeed all that is true. Christianity at its best did do all of that, and more. But there is another side to this Christian story, one that is worlds away from the bookish monks and careful copyists of legend. (– Nixey, Darkening Age, p. 140f, my bolding)

If we are still willing to read Nixey’s book after such a bald assertion about what to expect we will be taken aback to find that Tim O’Neill’s warning is very wide of the mark. We would not expect to read the following passage about the philosophical works and the attitude of “Christian clerics” more widely in Nixey’s work (again with my emphasis):

Even philosophers like Plato, whose writings fitted better with Christian thought – his single form of ‘the good’ could, with some contortions, be squeezed into a Christian framework – were still threatening. Perhaps even more so: Plato would continue to (sporadically) alarm the Church for centuries. In the eleventh century, a new clause was inserted into the Lenten liturgy censuring those who believed in Platonic forms. ‘Anathema on those,’ it declared, ‘who devote themselves to Greek studies and instead of merely making them a part of their education, adopt the foolish doctrines of the ancients and accept them as the truth.’38

For many hard-line Christian clerics, the entire edifice of academic learning was considered dubious. In some ways there was a noble egalitarianism in this: with Christianity, the humblest fisherman could touch the face of God without having his hand stayed by quibbling scholars. But there was a more aggressive and sinister side to it, too. St Paul had succinctly and influentially said that ‘the wisdom of this world is foolishness with God’.39 This was an attitude that persisted. Later Christians scorned those who tried to be too clever in their interpretation of the scriptures. One writer railed furiously at those who ‘put aside the sacred word of God, and devote themselves to geometry . . . Some of them give all their energies to the study of Euclidean geometry, and treat Aristotle . . . with reverent awe; to some of them Galen is almost an object of worship.’40

And so, in part from self-interest, in part from actual interest, Christianity started to absorb the literature of the ‘heathens’ into itself. Cicero soon sat alongside the psalters after all. Many of those who felt most awkward about their classical learning made best use of it. The Christian writer Tertullian might have disdained classical learning in asking what Athens had to do with Jerusalem – but he did so in high classical style with the metonymy of Athens’ standing in for ‘philosophy’ and that prodding rhetorical question. Cicero himself would have approved. Everywhere, Christian intellectuals struggled to fuse together the classical and the Christian. Bishop Ambrose dressed Cicero’s Stoic principles in Christian clothes; while Augustine adapted Roman oratory for Christian ends. The philosophical terms of the Greeks – the ‘logos’ of the Stoics – started to make their way into Christian philosophy.51

. . . . . .

Christianity was caught in an impossible situation. Greek and Roman literature was a sump of the sinful and the satanic and so it could not be embraced. But nor could it entirely be ignored either. It was painfully obvious to educated Christians that the intellectual achievements of the ‘insane’ pagans were vastly superior to their own. For all their declarations on the wickedness of pagan learning, few educated Christians could bring themselves to discard it completely. Augustine, despite disdaining those who cared about correct pronunciation, leaves us in no doubt that he himself knows how to pronounce everything perfectly. In countless passages, both implicitly and explicitly, his knowledge is displayed. He was a Christian, but a Christian with classical dash and he deployed his classical knowledge in the service of Christianity. The great biblical scholar Jerome, who described the style of sections of the Bible as ‘rude and repellent’,49 never freed himself from his love of classical literature and suffered from nightmares in which he was accused of being a ‘Ciceronian, not a Christian’.50

. . . . . .

Philosophers who wished their works and careers to survive in this Christian world had to curb their teachings. Philosophies that treated the old gods with too much reverence eventually became unacceptable. Any philosophies that dabbled in predicting the future were cracked down on. Any theories that stated that the world was eternal – for that contradicted the idea of Creation – were, as the academic Dirk Rohmann has pointed out, also suppressed. Philosophers who didn’t cut their cloth to the new shapes allowed by Christianity felt the consequences. In Athens, some decades after Hypatia’s death, a resolutely pagan philosopher found himself exiled for a year. (pp. 147-152)

Yet those paragraphs really are from Catherine Nixey’s own book and not from Tim O’Neill’s criticism of it. Even in focussing on “the other side” of the story Nixey still reminds readers that that narrative was neither all black nor all white. Continue reading “Christians, Book-Burning, Temple Destruction and some balance on Nixey’s popular polemic”