The first part of this series concentrated on Hasert’s research into the relationship between the gospels of Luke and Matthew. Here we examine the evidence for the connections between the Gospel of Luke and Paul’s life and letters. But we begin with what Hasert interpreted as the third evangelist’s denigration of the Twelve, especially when contrasted with their treatment in the Gospel of Matthew. (See the previous post for bibliographic and author references.)

Salt of the earth no more

Matthew’s Jesus addresses his (twelve) disciples and tells them they are the salt of the earth (5:13). Luke omits those words; Luke’s Jesus does not so compliment the twelve.

Bad timing

Luke finds a vicious way to twist the knife into the Twelve when he moves the scene of the disciples arguing amongst themselves about who will be the greatest into the Last Supper, immediately after Jesus told them that one of them would betray him.

Luke 22:

21 But the hand of him who is going to betray me is with mine on the table. 22 The Son of Man will go as it has been decreed. But woe to that man who betrays him!” 23 They began to question among themselves which of them it might be who would do this.

24 A dispute also arose among them as to which of them was considered to be greatest. 25 Jesus said to them, “The kings of the Gentiles lord it over them; and those who exercise authority over them call themselves Benefactors. 26 But you are not to be like that. Instead, the greatest among you should be like the youngest, and the one who rules like the one who serves. 27 For who is greater, the one who is at the table or the one who serves? Is it not the one who is at the table? But I am among you as one who serves. 28 You are those who have stood by me in my trials. 29 And I confer on you a kingdom, just as my Father conferred one on me, 30 so that you may eat and drink at my table in my kingdom and sit on thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel.

Such a relocation of this incident makes a complete mockery of the disciples, intimating that they are ironically disputing over which of them would betray Jesus.

Peter’s light fades from view

We know Matthew’s famous moment when Jesus declared Peter to be the possessor of the keys to the kingdom and the rock upon which the church was to be built (16:18-19). Luke’s Jesus finds no occasion on which to bestow such honourable status upon Peter.

Democratizing the family

In Matthew 12:49 Jesus once again confers special status upon his disciples:

Pointing to his disciples, he said, “Here are my mother and my brothers. (NIV)

Luke, on the contrary, has Jesus say that any and everyone (not only his disciples) who hear and do the words of Jesus are his mother and brothers, (8:21):

He replied, “My mother and brothers are those who hear God’s word and put it into practice.” (NIV)

Who is the faithful servant?

Hasert interpreted Luke’s account of Jesus contrasting the faithful and unfaithful servants as symbolic of Paul and Peter, 12:41-45:

41 Peter asked, “Lord, are you telling this parable to us, or to everyone?”

42 The Lord answered, “Who then is the faithful and wise manager, whom the master puts in charge of his servants to give them their food allowance at the proper time? 43 It will be good for that servant whom the master finds doing so when he returns. 44 Truly I tell you, he will put him in charge of all his possessions.45 But suppose the servant says to himself, ‘My master is taking a long time in coming,’ and he then begins to beat the other servants, both men and women, and to eat and drink and get drunk. (NIV)

With Paul’s description himself as a faithful servant in mind Hasert saw the faithful manager of the household in Luke 12 as an allusion to Paul. Notice Paul’s self-portrayal in 1 Corinthians 4:1-2:

This, then, is how you ought to regard us: as servants of Christ and as those entrusted with the mysteries God has revealed. 2 Now it is required that those who have been given a trust must prove faithful. (NIV)

Kicking the Twelve

In Luke we find “the Twelve are accused of

- hypocrisy

- love of power

- denial of the Lord out of fear of the people (Luke 12:1-21)

- inactivity (13:6-9)

- disbelief (17:5)

- ungrateful oblivion of their Saviour (17:12-17)

- and, finally, lack of understanding of the most holy: the Last Supper and the death of the Lord.“

(Wittkowsky summing up Hasert’s summary, p. 13 — my formatting)

Enter the Seventy to set the standard

Recall also Matthew’s Jesus forbidding the disciples to go to the gentiles and least of all to the Samaritans (Matthew 10:5). Luke sets up a sharp contraposition between the sending of the Twelve and the commissioning of the Seventy. The Seventy are apparently

appointed in Samaria and sent to preach the Gospel to the Samaritans, i.e. non-Jews, which stands in complete contradiction to Matt 10.5. (p. 13)

We mentioned above Hasert’s suggestion that Luke’s faithful and wicked servants represent Paul and Peter. Other allusions to Paul in the Gospel of Luke, according to Hasert, are found in Jesus’ mission for the Seventy: e.g. snakes will not harm them: Luke 10:19 and Acts 28:3-6

Paul versus Peter

The same is said to be found in the parable of the unjust steward (Luke 16:1-8), the story of Zacchaeus (Luke 19:1-10) and possibly in the parable of the prodigal son where Paul is opposed to his “older brother” (Peter).

Hasert further saw Luke implicitly referencing “an open and zealous, almost irreconcilable enmity between Peter and Paul”:

Luke 12:13-14

13 Someone in the crowd said to him, “Teacher, tell my brother to divide the inheritance with me.”

14 Jesus replied, “Man, who appointed me a judge or an arbiter between you?” (NIV)

Luke 12:51-53

51 Do you think I came to bring peace on earth? No, I tell you, but division. 52 From now on there will be five in one family divided against each other, three [James, Peter, John – Gal 2.9] against two [Paul and Barnabas; later Paul and Luke – Gal 2.9, 2 Tim 4.11] and two against three. 53 They will be divided, father against son and son against father, mother against daughter and daughter against mother, mother-in-law against daughter-in-law and daughter-in-law against mother-in-law.” (NIV)

Luke 12:57-59

57 “Why don’t you judge for yourselves what is right? 58 As you are going with your adversary to the magistrate, try hard to be reconciled on the way, or your adversary may drag you off to the judge, and the judge turn you over to the officer, and the officer throw you into prison. 59 I tell you, you will not get out until you have paid the last penny.” (NIV)

Finally,

The language of Luke shows many similar feature with that of Pauline epistles. Hasert does not make any distinction between authentic and non-authentic epistles; he does provide, though, a considerable number of examples form the first group. (p. 14)

But…

I find some of the above suggested allusions to Paul in the Gospel of Luke to be strained (e.g. the division between two and three is paired with divisions among fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, and would expect that there should be similar allusions in those roles as well; besides, the account of divisions and warnings directed at both parties hardly seems to favour Paul over Peter). But I do remind myself that I am only reading a summary of a summary. I don’t have access to Hasert’s 1845 original, Die Evangelium, ihr Geist, ihre Verfasser und ihr Verhältnis zu einander.

Lists and tables

More positively I will conclude some of the examples of similarities between the language in Luke’s Gospel and Paul’s epistles that Wittkowsky finds stronger than others:

| Luke 10.7-8

Stay there, eating and drinking whatever they give you, for the worker deserves his wages. Do not move around from house to house. “When you enter a town and are welcomed, eat what is offered to you. |

1 Cor 10.27

If an unbeliever invites you to a meal and you want to go, eat whatever is put before you without raising questions of conscience. |

| Luke 10.20

However, do not rejoice that the spirits submit to you, but rejoice that your names are written in heaven.” |

Phil 4.3

Yes, and I ask you, my true companion, help these women since they have contended at my side in the cause of the gospel, along with Clement and the rest of my co-workers, whose names are in the book of life. |

| Luke 11.49

Because of this, God in his wisdom said, ‘I will send them prophets and apostles, some of whom they will kill and others they will persecute.’ |

1 Thess 2.15

who killed the Lord Jesus and the prophets and also drove us out. They displease God and are hostile to everyone (I believe this verse is an interpolation, but see comments below.) |

| Luke 12.42

The Lord answered, “Who then is the faithful and wise manager, whom the master puts in charge of his servants to give them their food allowance at the proper time? |

1 Cor 4.1-2

This, then, is how you ought to regard us: as servants of Christ and as those entrusted with the mysteries God has revealed. 2 Now it is required that those who have been given a trust must prove faithful. |

| Luke 12

(In general) |

1 Cor 4.1-5

This, then, is how you ought to regard us: as servants of Christ and as those entrusted with the mysteries God has revealed. 2 Now it is required that those who have been given a trust must prove faithful. 3 I care very little if I am judged by you or by any human court; indeed, I do not even judge myself. 4 My conscience is clear, but that does not make me innocent. It is the Lord who judges me.5 Therefore judge nothing before the appointed time; wait until the Lord comes. He will bring to light what is hidden in darkness and will expose the motives of the heart. At that time each will receive their praise from God. |

| Luke 18.1

Then Jesus told his disciples a parable to show them that they should always pray and not give up. |

Rom 1.10; 1 Thess 5.17 (cf 2 Thess 1.11) etc

in my prayers at all times . . . . . pray continually, . . . . . (With this in mind, we constantly pray for you, …) (Again, 2 Thess is not generally considered an authentic Pauline letter, but see note below.) |

| Luke 20.38

He is not the God of the dead, but of the living, for to him all are alive.” |

Rom 14.8

If we live, we live for the Lord; and if we die, we die for the Lord. So, whether we live or die, we belong to the Lord. |

| Luke 21.19

Stand firm, and you will win life. |

Rom 2.7, 2 Cor 1.6 etc

To those who by persistence in doing good seek glory, honor and immortality, he will give eternal life. . . . . If we are distressed, it is for your comfort and salvation; if we are comforted, it is for your comfort, which produces in you patient endurance of the same sufferings we suffer. |

| Luke 21.24

They will fall by the sword and will be taken as prisoners to all the nations. Jerusalem will be trampled on by the Gentiles until the times of the Gentiles are fulfilled. |

Rom 11.25

I do not want you to be ignorant of this mystery, brothers and sisters, so that you may not be conceited: Israel has experienced a hardening in part until the full number of the Gentiles has come in |

| Luke 21.34

“Be careful, or your hearts will be weighed down with carousing, drunkenness and the anxieties of life, and that day will close on you suddenly like a trap. |

1 Thess 5.3-8

While people are saying, “Peace and safety,” destruction will come on them suddenly, as labor pains on a pregnant woman, and they will not escape. 4 But you, brothers and sisters, are not in darkness so that this day should surprise you like a thief. 5 You are all children of the light and children of the day. We do not belong to the night or to the darkness. 6 So then, let us not be like others, who are asleep, but let us be awake and sober. 7 For those who sleep, sleep at night, and those who get drunk, get drunk at night. 8 But since we belong to the day, let us be sober, putting on faith and love as a breastplate, and the hope of salvation as a helmet. |

| Luke 22.19-20

And he took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body given for you; do this in remembrance of me.” 20 In the same way, after the supper he took the cup, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is poured out for you. |

1 Cor 11.23-25

For I received from the Lord what I also passed on to you: The Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed, took bread, 24 and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, “This is my body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of me.” 25 In the same way, after supper he took the cup, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood; do this, whenever you drink it, in remembrance of me.” |

Other researchers conclude that the final canonical form of the Gospel of Luke was finalised as late as the mid second century, around the same time as the pastoral epistles in Paul’s name appeared. If Hasert finds as many similarities in Luke to the non-authentic Pauline letters as he does to the authentic Paulines, I would suggest that that is additional data to be used in support of the thesis that the final author or redactor of the Gospel of Luke (and Acts) was not so much a follower of Paul (that is, not the Luke who supposedly accompanied Paul in his life-time) but was as interested in reshaping Paul to make him suitable for “orthodoxy”. If we hold back from seeing as many or as trenchant criticisms of Peter in Luke’s gospel as Hasert does, we may instead notice a more dedicated focus on a narrative that attempts to unite, to equalise, the factions of Paul and Peter.

Wittkowsky notes,

Nowadays this problem is not a broadly discussed one. At the SNTS Annual Meeting in Louvain (2012) Michael Wolter in his response to a paper by Daniel Marguerat pointed at a large number of similarities between the texts of Luke and Paul, asking for an explanation. Unfortunately, Marguerat had no explanation for this fact; it seems that no answer can be found either in all the main commentaries of the last one hundred years which insist on assuming Luke’s ignorance of Pauline letters. See, however, Goulder, Luke, 129-46 (Chapter 4: “Paul”) (p. 14)

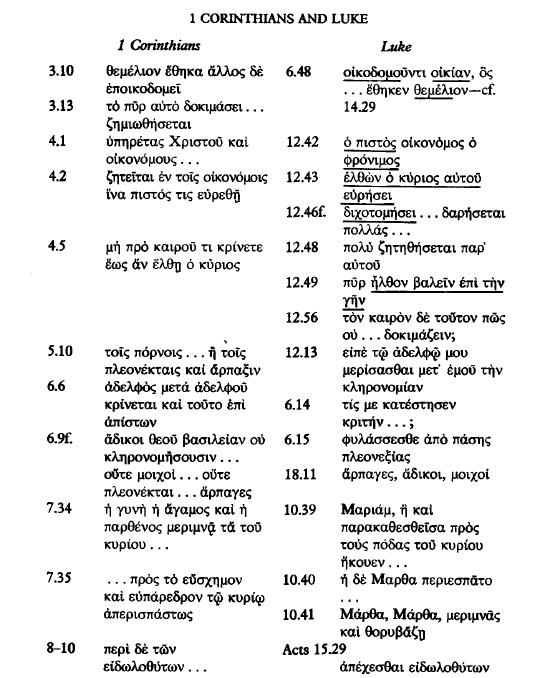

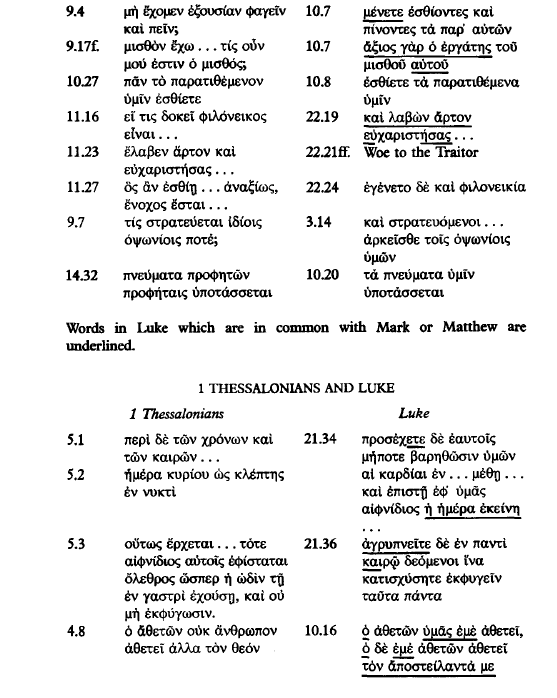

Michael Goulder’s chapter on Paul and Luke requires another post or three, but I will add here two comparative tables that conclude Goulder’s chapter.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- Samaria in the Persian Period - 2024-04-15 11:49:57 GMT+0000

- No Evidence Jerusalem/Judea had a “Writing Culture” in Persian times — Israel Finkelstein - 2024-04-12 09:45:34 GMT+0000

- Questioning the Hellenistic Date for the Hebrew Bible — continuing - 2024-04-11 20:54:16 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Archive.org lists that title (https://archive.org/details/MN41964ucmf_10), but the document uploaded is James Bennett’s Lectures on the Acts of the Apostles. (Oddly, the PDF file is some truncated document in Fraktur which I did not have time to identify).

Out of curiosity, I searched for & found Bennett’s Lectures listed at Archive.org (https://archive.org/details/MN41964ucmf_9). The document uploaded there, however, is Johannes Schneider’s Die Christusschau des Johannesevangeliums.

A search for Schneider came up empty, though perhaps further musical chairs might uncover Hasert’s tome.

Die Evangelien, ihr Geist, ihre Verfasser und ihr Verhältniß zu einander : Ein Beitr. zur Lösung d. krit. Fragen über d. Entstehung ders.

Autor / Hrsg.: Hasert, Christian A.

Verlagsort: Leipzig | Erscheinungsjahr: 1852 | Verlag: Wigand

Signatur: 8051869 Exeg. 337 n 8051869 Exeg. 337 n

Permalink: http://www.mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10410569-3

FYI: linked to from https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_Adolf_Hasert

Hasert, Christian Adolf (1845). Die Evangelien, ihr Geist, ihre Verfasser und ihr Verhältniss zu einander: ein Beitrag zur Lösung der kritischen Fragen über die Entstehung derselben. Wigand. @ https://books.google.com/books?id=GKleAAAAcAAJ

FYI:

You can get page images of old books from books.google @ https://books.google.com/books/content?id=GKleAAAAcAAJ&pg=PR3&img=1&zoom=3&hl=en&sig=ACfU3U3HAgazbjIhPAmmLuMZ9Yypig21qw

and croppped images @ https://books.google.com/books/content?id=GKleAAAAcAAJ&pg=PR3&img=1&zoom=3&hl=en&sig=ACfU3U3HAgazbjIhPAmmLuMZ9Yypig21qw&ci=197%2C1405%2C546%2C207&edge=0

note. the crop size may be manually adjusted by altering the &ci=197%2C1405%2C546%2C207parameters. (the URL hexadecimal %2C decodes to a comma (,).)

Does anyone know of an online or open source translating tool that recognizes that Gothic(?) font?

Per the Bavarian State Library website in English mode (click on the UK flag top right) @ http://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/fs1/object/display/bsb10410569_00001.html

PDF-Download is availble with text OCR optional.

[Search within tome] [PDF-Download] [OPAC] [DFG-Viewer]

https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=de&tl=en&u=https%3A%2F%2Fdownload.digitale-sammlungen.de%2FBOOKS%2Fdownload.pl%3Fid%3Dbsb10410569

Per the Download Form, you have to click on the UK flag again to enable English mode @ https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/BOOKS/download.pl?vers=e&id=10410569&ersteseite=1&letzteseite=464&nr=&x=4&y=5

Excellent YouTube vid:

The History of Typography – Animated Short @ https://youtu.be/wOgIkxAfJsk

FYI: As Italic type became more common, popular books had to be printed with mirrored pages of Blackletter (Gothic script), since the older generation (and Germans ???) could not read Italic.

Per Google Books (ref. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Books):

Books in the public domain are available for “full view” and can be downloaded as: PDF

or viewed online as:

EBOOK @ https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=GKleAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb_hover&pg=GBS.PA251

note. selected text may be translated via a pop up context menu.

Sounds like some corruption has entered into their system. They need to be notified but I don’t see any contact details to enable that. There must be something somewhere. Maybe some clue can be found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_Archive — but that’s a lot of reading.

“[Per] that period in New Testament studies when it was considered quite natural that Luke ”should have been” a sort of critic and one who deconstructed the Gospel of Matthew. This starting point even dominated scholarship in the nineteenth century. The contemporary authors of the time. mostly German. would have been surprised to hear that precisely the “scattering” should be seen as a huge problem with regard to Luke’s dependence on Matthew. These scholars. who have been unmeritedly forgotten, can in part be considered as the predecessors of Austin Farrer, Michael Goulder, Mark Goodacre and …Eric Franklin” (Wittkowsky 2016, p. 4) Ibid.

Per Farrer hypothesis @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Farrer_hypothesis

In his 1955 paper On Dispensing with Q, Austin Farrer made the case that if Luke had been acquainted with the gospel of Matthew, there would be no need to postulate a lost Q gospel. Farrer’s case rested on the following points:

The Q hypothesis was formed to answer the question of where Matthew and Luke got their common material if they did not know of each other’s gospels. But if Luke had read Matthew, the question that Q answers does not arise.

We have no evidence from early Christian writings that anything like Q ever existed.

When scholars have attempted to reconstruct Q from the common elements of Matthew and Luke, the result does not look like a gospel.

Although many scholars originally thought of Q as a sayings gospel, a collection of teachings with no narrative content, all alleged reconstructions of Q from the common parts of Matthew and Luke include narrative about John the Baptist, Jesus’ baptism and temptation in the wilderness, and his healing of a centurion’s servant.

However, they don’t include an account of Jesus’ death and resurrection.

But from the earliest Christian writings, we see a strong emphasis on precisely the element that a putative Q omits, Jesus’ death and resurrection.

Some scholars have attempted to overcome problems with Q reconstructions by claiming we cannot know the actual contents of the Q gospel. However, postulating Luke’s acquaintance with the gospel of Matthew overcomes these same problems and gives the source for the common material.

Does it, however, account for the way it’s organized?

One of the things I’ve heard about Q is that the originators of the hypothesis noted that this material is in a few blocks in Luke, but scattered in various places in Matthew. If this is the case, it seems a bit odd that Luke would have copied it from Matthew.

Collecting everything that’s common to Matthew and Luke and isn’t in Mark seems to me to be a great prescription for collecting some stuff that really doesn’t belong with the rest. Of course, there’s no way of knowing what that stuff is.

Wittkowsky discusses in some length just how common in the nineteenth century was the idea that Luke knew and rewrote Matthew and that no-one considered it problematic at all that Luke would scatter the material in Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount.

We are in slippery territory when we build cases on what we imagine an author “would” do. We need cogent reasons, evidence.

Thanks for this series of posts, Neil. I’ve been on the fence about “Q” for twenty years but lately I’ve been leaning towards the Farrer Hypothesis. I can see Wittkowsky’s (and Goodacre’s) chapter on Google Books, and I think he does a good job of outlining the case that Luke is “representative of the ‘Pauline’ Christianity involved in a theologically significant dialogue, including sharp polemics against the theologians of another Christian school, conveniently called ‘Jewish-Christian.’ The Gospel of Matthew provides, according to this interpretation, the most important negative pretext to the Gospel of Luke…” (pg. 24).

Goulder reading list per, Goodacre, Mark (19 July 2016). “The Farrer Hypothesis”. In Stanley E. Porter. The Synoptic Problem: Four Views. Bryan R. Dyer. Baker Publishing Group. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4934-0445-2. @ https://books.google.com/books?id=8At4DAAAQBAJ&pg=PT73

Goulder, M. D. (1996). ”Is Q a Juggernaut?”, Journal of Biblical Literature 115: 667–681.

Goulder, M. D. (1989). ”Luke: A New Paradigm”. Volume 20 of Journal for the study of the New Testament: Supplement series, ISSN 0143-5108. 2 vols. JSOT Press. ISBN 978-1-85075-101-4.

Michael D. Goulder (March 5, 2002). “Is Q a Juggernaut, Michael Goulder”. http://www.markgoodacre.org. Retrieved 14 April 2017. “This article first appeared in Journal of Biblical Literature 115 (1996), pp. 667-81.” – available online @ http://www.markgoodacre.org/Q/goulder.htm

This raises an interesting question: for the material that’s in all three Gospels: Mark, Matthew and Luke, are the differences between Matthew and Luke due to additions of Matthew over Mark, or deletions of Luke from Mark? Or can the case be made that Luke differs from both in those cases where he wants to harmonize with Paul?

This seems to feed my suspicions of the importance of Marcion in the mix of the development of the gospel, as I understand that Marcion used an ur-Luke gospel which leaned heavily upon Flavius Josephus along with a grab-bag of Pauline epistles. Marcion’s publishing of these documents would engender the reaction amongst the proto-orthodox to create a canon of official documents, claiming that Marcionite heretics had stolen and perverted the epistles of Paul.

To my inexpert senses, Pauline religious expression seems much closer to what I understood Marcionite christianity to have been. Could not what we have received of the ‘original’ Pauline materials be expurgated and edited versions of what was reclaimed from Marcion? And, an ur-Luke? Is the Luke we have a sanitized version of what the Marcionites were using? Or, did a quasi-gnostic Marcionite version exist alongside a proto-orthodox version of the Lukan storyline?

I have tended to view Luke as a later attempt to ‘harmonize’ the whole Peter/Paul dichotomy.

Our views are in some ways similar. (You may also be aware I have posted often on the questions you raise.)

I can’t say I have any “proof” but I tend to like the idea espoused by a few scholars that the Gospel of Luke as we know it was the last of our canonical gospels and written with a catholicising agenda, attempting to tie together what had till then been competing “traditions” (with the leadership of the church at Rome).

Yes, I’d place GLuke as the last of the Synoptics, for sure. As for John…well, it seems like later christology, but I can see the APaul grooving on much of the Johanine material. I date the late Synoptics well in to the second century. GJohn seems to have the oldest extant snippet in Rylands P52, but the tolerance interval leaves a lot of room and includes the middle of the second century.

After the threat posed by the Marcionite churches, it seems to me that the proto-orthodox would pull together what traditions they had amongst the congregations, trying to shoehorn in variant congregations by adapting storylines, and coming down to sets of stories, one which would have been the ur-Luke used by Marcion as part of his gospel. Since it had to be reworked to make it fit the proto-orthodox dogma, it would have been the late-date candidate for a universal harmonization effort. The proto-orthodox seem to be more the ‘Judaizers’ the Pauline author warned against, yet they co-opted the teachings. Because they were their teachings, or because they were popular teachings with strong and influential adherents?

• “Did Luke Have a Doctrine of the Atonement? Mailbag September 24, 2017”. The Bart Ehrman Blog.

A “Lukan model of non sin debt atonement” cites the claim of certain verses not originally being in Luke’s Gospel :

Comment by 1Heidegger1!—29 May 2022—per”The Christ Myth Theory”. Internet Infidels Discussion Board.