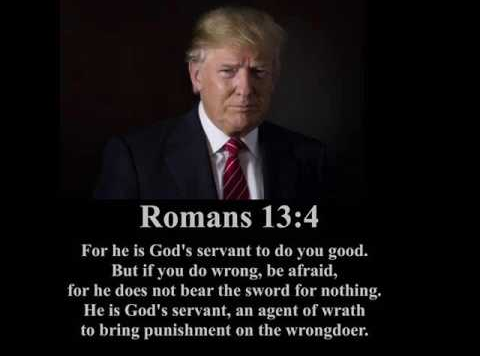

The Religion Prof tagged those words with this image:

Meanwhile, another “religion prof” has singled out his research into this same passage for special attention with a title that on the basis of a confusing document from an ancient civilization strangely advises modern readers on their contemporary civic responsibilities:

When to Disobey Government – Quick Look at Romans 13

This post is a recycling of appreciation from a “religion master”, again providing instruction for readers today on how they should relate to political authorities:

How Should Christians Relate to Governing Authorities? Michael Bird Clarifies

How strange. Would anyone today turn to the recordings of the Sibyl Oracle for messages of guidance? Or to Hammurabi’s Code for how to treat a purveyors of faulty goods? Or to Plato or the wisdom of Imhotep? Or to the heavenly influences on human affairs according to Porphyry?

I am all for studying ancient documents. I have always loved studying ancient history. But the point has always been to understand how the ancients thought and lived, not how I can learn from them as guiding lights for my own life.

But notice how religion profs and masters take an ancient writing and strain and pull to make it somehow “relevant” as an instruction to readers today:

Consider Stanley Porter’s condition: qualitative superiority. “According to Porter, Paul only expects Christians to obey authorities who are qualitatively superior, that is, authorities who know and practice justice.” (449) The Greek for “governing authorities” (exousiais hyperechousais) seems to suggest this, given that hyperecho carries with it a “qualitative sense of superiority in quality.” (449) Therefore, the only governing powers to which Christians should submit are those that reflect the qualitatively divine justice they’ve been entrusted to bear, enact, and steward.

Woah there! Where to begin?

A raft of scholars have found reason to doubt that the passage in question was even original to the writing addressed to Romans: Pallis (1920); Loisy (1922: 104, 128; 1935: 30-31; 1936: 287); Windisch (1931); cf. Barnikol (1931b); Eggenberger (1945); Barnes (1947: 302, possibly); Kallas (1964-65); Munro (1983: 56f., 65-67); Sahlin (1953); Bultmann (1947). And who was this Paul, anyway? What independent evidence do we have to establish anything for certain? And how does one get from “a qualitative sense of superiority in quality” to modern readers’ concepts of “God” and “divine justice” (whatever “divine” justice is)? What was the original context and provenance of the document — we can only surmise — and what in the name of Mary’s little lamb does it have to do with anything in today’s world?

It would be naïve to suggest this passage is the last word on church/state relations, given that our conception of “state” is conditioned by post-Enlightenment views and the original context for Paul’s instructions came during a time of relatively benevolent and well-behaved authorities.

Amen. But why oh why does it deserve to be introduced into today’s discussion at all? Why not bring in Plato as well?

Bird reasons there are occasions resistance to governing authorities is both required and demanded by Christian discipleship. “Just as we have to submit to governing authorities on the basis of conscience, sometimes we have to rebel against governments because of the same conscience.” (450) When governments misuse their power, sometimes Christians must say, “We must obey God rather than human beings!” (Acts 5:29)

Bird likes John Stott’s summary of this discussion: “Whenever laws are enacted which contradict God’s Law, civil disobedience becomes a Christian duty.”

Deep. Just what everyone instinctively knows and follows. We all acknowledge the need for some form or organization and cooperation. We are social mammals, after all. And we all live this way for the sake of peace and getting along. But of course those of us who have crises of conscience will very often find themselves resisting or evading those causing them such grief. It’s the stuff of thousands of movies and novels and pages of history books. “Christian discipleship” is no exception to the common experience of humanity and living in organized societies. Just dressing up the same conflict in the verbiage of one’s particular ideology makes no difference. My god, Sophocles’ Antigone has remained a timeless classic because of the way it epitomizes the theme of the individual standing up for right against the state.

This human universal owes precious little to a few words written from a vaguely understood context and provenance in a civilization far removed from ours.

And religion careers and publishing businesses are built on the determination to wrestle with problematic Roman era discourses in the belief that they offer something exceptional for initiates into the arcane mysteries.