.

This post is a continuation of Making Sense of the Letters and Travels of Ignatius (Peregrinus?)

TDOP = The Death of Peregrinus by Lucian. Harmon’s translation here.

| All posts so far in this series: Roger Parvus: Letters Supposedly Written by Ignatius

|

.

So far I have called attention to the many similarities between Peregrinus and the author of the so-called Ignatians.

Failed explanations for the similarities

I have explained that, to account for the similarities, it is not enough to simply claim that Lucian, for his portrait of Peregrinus, probably borrowed from Ignatius.

It is not enough, for instance,

- to say with William Schoedel that “Lucian (as Lightfoot and others have suggested) probably had Ignatius in mind when he wrote the following concerning Peregrinus: ‘They say that he sent letters to almost all the famous cities more or less as testaments, counsels, and laws; and he appointed … certain of his companions as ambassadors. . . for the purpose, calling them messengers of the dead and couriers of the shades . . . ” (Ignatius of Antioch, p. 279). . . .

- Or to say with Allen Brent that “Lucian, as he describes Peregrinus, endows him with many of the characteristics of Ignatius as typical of an imprisoned Christian martyr.” (Ignatius of Antioch – A Martyr Bishop and the origin of the Episcopacy, p. 50).

That explanation doesn’t work. That kind of borrowing by Lucian would only have compromised his ridicule of Peregrinus. He couldn’t have expected to convincingly expose Peregrinus by substituting a lot of characteristics from someone else, especially when he was writing so soon after the demise of his target. People would have noticed that his portrait was false.

More convincing explanations

But I have also now shown that the letters themselves contain puzzling features that point to a different explanation for the similarities. The similarities exist because the letters were in fact written by Peregrinus, but the puzzles exist because changes were later made to the letters to disguise his authorship.

Fortunately, with help from TDOP, enough telltale traces of the true provenance of the letters remain so that the puzzles can be solved.

Fortunately, with help from TDOP, enough telltale traces of the true provenance of the letters remain so that the puzzles can be solved.

- Authorship by Peregrinus provides a more convincing reason for the urgency of the request that Ambassadors of God be sent from Asia to Antioch.

- And that request for Asian Ambassadors matches up with the presence of Asian delegates in Syria who, according to Lucian, helped, defended and encouraged Peregrinus.

- My theory also provides a more convincing reason for the request that a most God-pleasing council be convoked.

- And it can plausibly reconstruct the circumstances of Peregrinus’ arrest and detect the route that was originally in the letters.

- It can give a definite meaning to the otherwise vague expression “May I have the joy of you.”

- Moreover the theory can explain, for instance, why the name of Polycarp is not found in the letter to the Smyrneans, but is found awkwardly lodged in another letter.

- And why, for instance, only in the so-called letter to Rome is there no mention of a bishop, presbyters and deacons.

- And it can explain the ‘filtering out’ that has occurred in the church addressed by that letter.

Other lesser anomalies find similarly satisfying solutions.

And, of course, since Peregrinus at some point became an apostate, there is an overall plausible reason why a later Christian would have needed to disguise the letters if he wanted to use them.

.

Second Century Witness — or Lack Thereof — to an Ignatius of Antioch

My theory can explain too, why the name ‘Ignatius’—with a single questionable exception to be considered shortly—is nowhere to be found in any second-century Christian writings outside of the letter collection itself.

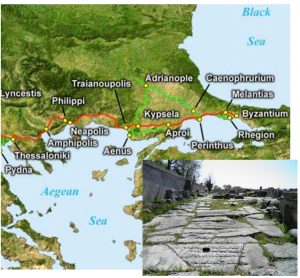

One would expect that if the scenario presented by the Ignatians in their present state was authentic, Ignatius of Antioch would receive frequent mention in the early record. After all, here supposedly was an early Christian bishop of one of the major cities in the Roman Empire who travelled to Rome itself for his martyrdom. He supposedly travelled, then, from Antioch through important cities and ports in Asia Minor, then through Philippi and the other towns and cities on the Via Egnatia, and then on to Italy and Rome.

And everywhere he went he received visits from members of the local churches. And “even those that did not lie on my actual route hastened to see me in city after city.” (IgnRom. 9:3).

And everywhere he went he and his religious brethren publicized his upcoming sacrifice, by letters and by messengers: “I am writing to all the churches, and I charge them all to know that I die willingly for God…” (IgnRom. 4:1); “You will write to the churches which lie in front…” (IgnPoly. 8:1)

The letters, moreover, connect him with Polycarp, making him a friend and mentor to a figure who himself was widely known to Christians.

It is safe to say that few second-century Christians received the amount of exposure enjoyed by the author of the letter collection. And that is why there has to be something wrong with the scenario presented by the Ignatians in their present state, for Ignatius of Antioch is absent from the second-century Christian record!

My theory can explain that absence.

- First, the author of the letters was not a bishop. He was a deacon.

- And he was not led to Rome. He was led back to Antioch.

- And he was not friends with Polycarp and did not write a letter to him. He wrote the letter to a bishop installed at Antioch after peace had been restored in the church there.

- And he did not die a martyr. The governor of Syria ultimately released him.

- And his name wasn’t Ignatius. It was Peregrinus, and although he was well-known and very popular with his fellow Christians for a time, he ultimately became an embarrassment to them when he became an apostate.

The considerable publicity for his prospective execution that he generated amongst them by letters, ambassadors, couriers and a Christian gathering at Antioch all dissipated once he was released and, especially, when he abandoned Christianity to become a Cynic philosopher. It was only thanks to a later Christian who took up the letters and made changes to them—including changing the name of their author—that Ignatius of Antioch came into being. But those changes were only made around 200 CE, too late for any second-century Christian to be aware of the new creation.

To Origen, writing around 235 CE, belongs the distinction of being the first to indisputably mention Ignatius, bishop of Antioch.

.

Polycarp’s Letter to the Philippians

I noted above that the second-century Christian record does contain one writing, outside of the letter collection itself, that arguably makes reference to Ignatius of Antioch. In chapter nine of the Letter of Polycarp to the Philippians there is a martyr named ‘Ignatius:’

(9:1) Therefore I exhort you all to obey the word of righteousness and to practice all endurance, which you also saw before your eyes not only in the blessed Ignatius and Zosimus and Rufus, but also in others from among you and in Paul himself and the other apostles;

(9:2) being convinced that all these did not run in vain, but in faith and righteousness, and that they are in their due place in the presence of the Lord, with whom they also suffered.

Ignatius, Zosimus and Rufus are apparently three men who had been martyred at Philippi, for the passage asserts that they were “from among you” (i.e., from among the Philippians), suffered before their eyes, and are now in the presence of the Lord. However the passage is imprecise enough that it could conceivably be understood to mean that the Philippians saw the three men suffering—but not dying—as they passed through Philippi and that they were put to death somewhere else.

And in line with that interpretation many scholars hold that there is nothing in the passage to prevent the Ignatius who is one of the three martyrs from being the Ignatius whose name is presently is at the head of each of the Ignatian letters.

And in support of this contention they can call upon two other passages in the Philippians letter, passages however that have always posed difficult problems for scholars. One of the passages occurs at the end of the letter. Polycarp writes:

(13:1) You and Ignatius wrote to me asking that, if any one goes to Syria, he take along the letters from you. I will do so if I have an opportunity, either I myself or someone I will send to be ambassador on your behalf and mine.

(13:2) We have sent you, as you directed, the letters of Ignatius that he sent to us, and all the others we had in our possession. They accompany this letter. From them you will be able to derive great benefit, for they embrace faith and endurance and every kind of edification which pertains to our Lord. And if you have any definite news concerning Ignatius and those who are with him, let us know.

The problem with this passage that scholars openly admit has not yet been resolved is that in chapter 9 Ignatius and his companions are spoken of as if they were already dead, but in chapter 13 they are spoken of as being still alive!

How is it that Polycarp knew of the martyrdom when he wrote chapter 9, but didn’t know it four chapters later?

Many solutions have been offered but nothing even close to a consensus has been reached.

- Some have simply suppressed the last sentence of 13:2 (e.g., Eusebius, the Acta Romana);

- some have rejected the whole Philippians letter as spurious (e.g., Schwegler, Baur, Zeller, Hilgenfeld);

- some have attempted strained retranslations of the offending passage (e.g., Pearson, Zahn, Funk, Lightfoot, Bauer).

- For a time a solution put forward by P.N. Harrison was very popular. He proposed that the letter was put together from what were originally two distinct letters. Someone stitched them together, he claimed, and, regrettably, they stitched them together backwards. That is to say, the earlier of the two letters was accidentally put at the end of the composite letter instead of its beginning. But gradually scholars recognized weaknesses in Harrison’s solution too, and many have abandoned it and returned to single-letter solutions.

The scholars who reject the authenticity of the Ignatians (e.g., Völter, Turmel, Loisy, Weijenborg, Rius-Camps, Joly, Lechner, Hübner, Vinzent) see chapter 13 as an interpolation. It was made, they contend, at the same time and by the same person who reworked the so-called Ignatians. The interpolator’s intent was apparently both to present Polycarp as the one who gathered the letters into a collection and to attach the collection to a real martyr. I agree.

Peregrinus, as it turned out, was only a would-be martyr.

When the interpolator decided to disguise his letters he went looking for an actual martyr to replace him and he found one in chapter 9 of Polycarp’s letter to the Philippians. It happens often enough in pseudepigraphical writing that the author attaches his fiction to a known figure from a previous generation. It adds some credibility to the work. He wants the reader to think: “I do recall that there was a martyr named Ignatius in Polycarp’s letter. These must be a set of letters written by him.” It was to be expected that someone disguising the letters of Peregrinus would try to attach them to another figure instead of just leaving them free-floating.

I think too that the carelessness that caused the confusion in chapter 13 of Philippians is reminiscent of the carelessness that the interpolator displayed in his reworking of Peregrinus’ letters. This is just another instance of the same.

- It can be added, for example, to his careless insertion of Polycarp’s name into IgnPoly. 7:2;

- and to his making the prisoner into a bishop in the letter to the Romans while letting him remain a deacon in the other six letters;

- and to his leaving the words “You are the passageway of those put to death for God” in the letter to the Ephesians even though the new itinerary he introduced ruled out a stop in Ephesus.

Other examples have been given. By his careless work ye shall know him!

Ignatius an interpolation in Polycarp’s letter? Pro and con

Before going on I want to clarify that a few of the partisans of interpolation in the Philippians letter think that even the name ‘Ignatius’ in chapter 9 may be an interpolation. They suspect that Zosimus and Rufus may have been the only Philippian martyrs named in the original letter. I find that proposal tempting only for one reason. I have identified Peregrinus as the one being replaced by Ignatius, and the folk etymology of ‘Ignatius’ associates it with the Latin word for fire (ignis). So the ‘fiery one’ would be a singularly apt—and humorous!—replacement name for Peregrinus, the man who chose to die by fire. Or, to use Lucian’s words, the man who “after turning into everything for the sake of notoriety and achieving any number of transformations, here at last has turned into fire.” (TDOP 1, Harmon).

Before going on I want to clarify that a few of the partisans of interpolation in the Philippians letter think that even the name ‘Ignatius’ in chapter 9 may be an interpolation. They suspect that Zosimus and Rufus may have been the only Philippian martyrs named in the original letter. I find that proposal tempting only for one reason. I have identified Peregrinus as the one being replaced by Ignatius, and the folk etymology of ‘Ignatius’ associates it with the Latin word for fire (ignis). So the ‘fiery one’ would be a singularly apt—and humorous!—replacement name for Peregrinus, the man who chose to die by fire. Or, to use Lucian’s words, the man who “after turning into everything for the sake of notoriety and achieving any number of transformations, here at last has turned into fire.” (TDOP 1, Harmon).

But I hesitate. Philippi was located on the Via Egnatia, the famous road built by and named after Gnaeus Egnatius in the second century BCE. And Ignatius is thought to be a later Latin form of Egnatius. It would not be surprising if that name was in use in the cities and towns along the Via Egnatia. Moreover, as I said above, pseudepigraphical writers often hang their creations on a real peg. So while folk etymology may be the reason the interpolator chose Ignatius for makeover instead of Zosimus or Rufus, I do not think the name ‘Ignatius’ in 9:1 is an interpolation.

Another problem in Polyarp’s letter

There is a second problematic passage in Polycarp’s letter to the Philippians, right at the beginning of the letter:

(1:1) I rejoice greatly with you in our Lord Jesus Christ [because you received the images of true love and sent on their way, as was given you, those bound in holy chains, which are diadems for those who have been truly chosen by God and our Lord, and] (1:2) because the steadfast root of your faith, renowned from earliest times, still lives on and bears fruit in our Lord Jesus Christ, who endured etc.

I have bolded and put in brackets the problematic part. The “images of true love” and “those bound in holy chains” would be Ignatius and his companions who were supposedly received and sent on their way to Rome by the Philippian Christians. And wouldn’t you know it, in the Greek there is a grammatical inconsistency which occurs, as William Schoedel acknowledges, in “precisely the section that contains the allusion to Ignatius and his companions.” (“Polycarp’s Witness to Ignatius of Antioch,” 1987, issue 41 of Vigiliae Christianae).

The first reason for Polycarp’s joy is introduced with a participial phrase (literally: “you having received”), while the second reason is introduced with a ‘because’ clause. The grammatical problem is serious enough that some kind of surgery is necessary to fix it. Schoedel discusses the possibilities and ultimately decides on the least invasive: The deletion of the “and” at the end of 1:1. He explains how easy it would have been for either Polycarp himself or a later copyist to be distracted and mistakenly put an “and” where it didn’t belong. He concludes his article by saying:

Defenders of the authenticity of Polycarp’s allusion to Ignatius and companions in Phil. 1:1 may regret that any emendation, however modest, is required to save the text. It may be hoped, however, that a sufficiently natural explanation of the data has been given to alleviate their distress and that it will soften the doubts of others about the witness of Polycarp to Ignatius. (p. 8)

Need I say that my distress was not alleviated nor were my doubts softened? Why should we attribute the carelessness to Polycarp or a copyist instead of an interpolator, especially in view of the corresponding problem in chapter 13?

Far from being a witness to the existence of an Ignatius of Antioch, the letter of Polycarp to the Philippians confirms our doubts. The problem passages occur precisely where the letter refers to Ignatius. And those problems would exist even if the so-called Ignatians were no longer extant and no one knew their contents. Alfred Loisy, in his The Birth of Christian Religion, writes:

“Moreover, the Epistle of Polycarp to the Philippians seems to have been interpolated into the collection of the Ignatian letters, by their author or editor, for the purpose of recommending them; this alone would seem to prove them apocryphal…” (p. 32).

He’s right. Authentic letters don‘t require bogus props.

.

“As one of our people said . . .”

There is one other second-century witness of sorts that needs to be considered. It is not a witness to the existence of an Ignatius of Antioch, but to the existence of a verse from one of the letters and to the “one of our people” who said it. Irenaeus, in his Against Heresies (5,28,4) writes:

As one of our people said, when he was condemned to the wild beasts because of his testimony to God, “I am the wheat of Christ, and am ground by the teeth of wild beasts, that I may be found the pure bread of God.”

The words Irenaeus is quoting are found in IgnRom. 4:1. Now what is curious here is the way that Irenaeus refers to the author of the quote as “one of our people.” Irenaeus must have known who the author of this quote was. It is not the kind of quote that would just float around unaccounted for. It is very personal and memorable.

Why then did Irenaeus not indicate who its author was? If he knew it as a quote by a bishop from Syria named Ignatius why would he have withheld that information? Why not let the quote redound to the honor of Ignatius? Irenaeus honors other heroes by name. He praises, for instance, Clement of Rome. And Polycarp, of course. Why withhold praise from Ignatius?

But one could object that often Irenaeus just says: “a certain presbyter said such and such… A certain elder said such and such…” Okay. But Ignatius was supposedly a bishop. Why did Irenaeus not at least say: “A certain bishop of ours, when he was condemned to the wild beasts etc.” Why does he withhold even the ecclesiastical station of the martyr?

My theory can account for Irenaeus’ reticence. When Irenaeus wrote his Against Heresies the letters of Peregrinus had not yet been converted into letters of Ignatius. Irenaeus knew the words he quoted were words of Peregrinus. He liked the quote but, even though twenty years had passed since the death of Peregrinus, it would still have been embarrassing to acknowledge that the words were his. Thus Irenaeus used the quote but conveniently omitted to say who the eloquent martyr was.

Irenaeus’ manner of proceeding might work in an individual instance, but there were undoubtedly many more quotes from the popular and edifying Peregrinus that later Christians wanted to use. Around 200 CE, when the persecution by Septimius Severus was gaining steam, someone came up with a way to use quotes from the letters that Peregrinus wrote when he expected to die a martyr. The solution was to disguise the letters and attribute them to a martyr named Ignatius.

Peregrinus was mined for the Pauline Pastorals and the ektroma?

I suspect, by the way, that some of the quotes in the letters of Peregrinus had already been mined earlier by whoever fabricated the Pauline Pastoral letters, for example, and the interpolation in 1 Corinthians 15: 3-11.

- Thus, for instance, 2 Tim. 1:16, “was not ashamed of my chains” was taken from IgnSmy. 10:2.

- And 2 Tim. 4:6, “for I am already being poured out as a libation” was taken from IgnRom. 2:2.

- Likewise the “premature baby” of 1 Cor. 15:8 would come from IgnRom 9:2: “But as for me, I am ashamed to be spoken of as one of them, for I am not worthy, since I am the last of them, and a preemie (child born prematurely). But I have obtained mercy to be someone, if I attain to God.”

The Greek word ektroma was used for premature live births, not just for stillborns. Thus Peregrinus, with his usual rhetorical exaggeration, is humbly taking a position below Paul whose name means ‘child; little one.’ Peregrinus is even less significant. He is a mere preemie.

From Ignatius to the Pastorals

Regarding this, although Paul Foster dates the Pastoral and Ignatians earlier than I do, what he says about the direction of dependence is pertinent:

The question remains as to the direction of dependence. This is not as easily resolved as may at first appear to be the case. The dating of the Pastorals is notoriously difficult. Arguments about the more primitive and complex forms of parallels are often easily reversed, and discussions about theological developments fail to recognize the pluriform and non-linear evolution of Christianity. The issue cannot be treated in detail here; suffice it to note that the latest period suggested for the composition of the Pastorals, the early second century, overlaps with the traditional date of the martyrdom of Ignatius in the reign of Trajan. The dating of the Ignatian correspondence may not be as secure as is often supposed, and may itself come from a later period. Perhaps all that can be concluded is that the balance of probability is in favour of Ignatius knowing 1 and 2 Timothy, rather than vice versa. (“The Epistles of Ignatius of Antioch and the Writings that later formed the New Testament, “ pp. 171-2 in The Reception of the New Testament in the Apostolic Fathers, edited by Andrew Gregory and Christopher Tuckett).

I will bring this section to a close by saying that no one named Ignatius of Antioch is indisputably mentioned in the second-century record. And, in contrast, someone named Peregrinus was known both to second-century Christians (Athenagoras and Tertullian) and to non-Christians (Lucian and Aulus Gellius).

.

The Bearer of Godly Things

I have argued that the proto-Catholic who modified the letters of Peregrinus found him a suitable replacement name, Ignatius, in the letter of Polycarp to the Philippians. But in the letter collection as it presently stands the prisoner has a second name, Theophorus, which means ‘the bearer of God.’ He is ‘Ignatius who is also Theophorus.’ The name ‘Theophorus’ is very distinctive. It is unknown as a proper name until its appearance in these letters. So if it had really been adopted by Peregrinus it could not help but identify him and make all the redactor’s efforts to disguise the letters a waste of time. ‘Theophorus’ must, then, be a replacement for some other name. And I think that, without engaging in excessive speculation, a good guess can be made as to the name it replaced.

When reading the letters it is hard not to miss how proud the prisoner is of the chains he bears. Maxwell Staniforth, in a note to his translation of the Ignatians, points out that “the curious pleasure which Ignatius takes in his chains recurs at nearly every mention of them in his letters.” (Early Christian Writings, p. 67)

When reading the letters it is hard not to miss how proud the prisoner is of the chains he bears. Maxwell Staniforth, in a note to his translation of the Ignatians, points out that “the curious pleasure which Ignatius takes in his chains recurs at nearly every mention of them in his letters.” (Early Christian Writings, p. 67)

The prisoner calls them his “spiritual pearls” (IgnEph. 11:2). In IgnSmyr. 11:9 he even uses his ultimate superlative, ‘most God-pleasing,’ for them. Allen Brent’s observation is on target:

Ignatius describes himself as ‘bound in bonds that evoke tremendous awe for the divine (theoprepestatoi)’. As such, he was like a hagiophoros in a pagan procession, a bearer of a divine object invoking awe for the divine. (Ignatius of Antioch – A Martyr Bishop and the origin of the Episcopacy, p. 156).

Now in IgnMag. 1:2 the prisoner uses theoprepestatoi again—this time to describe his name—and he immediately establishes a connection between it and his chains:

“For having been deemed worthy to bear a most God-pleasing name, in the chains I bear I sing to the churches…” (my emphases).

It does not seem to be too much of a stretch, therefore, to guess that the name Peregrinus gave himself when he was arrested was Hagiophorus i.e., the bearer of godly things. The godly things were his most God-pleasing chains. The person too who interpolated 1:1 of Polycarp’s Letter to the Philippians was apparently aware of the sanctity the prisoner conferred on his bonds, for the insertion describes the martyrs as

“bound in holy chains, which are diadems for those who have been truly chosen by God and our Lord.”

Finally, this guess would also explain yet another unusual feature found in the letters, one that appears in the inscription to the letter to the Smyrneans:

To the church of God the Father and Jesus Christ the beloved, which has mercifully obtained every gift, which has been filled with faith and love, which is not lacking in any gift, most pleasing to God and bearing godly things, which is at Smyrna in Asia, heartiest greeting in a blameless spirit and in the word of God.

I have italicized the expression that sits oddly after the author’s reference to God. I suspect but cannot prove that in the original version the Smyrneans were most pleasing to God and to the bearer of godly things i.e., to Peregrinus. The reason that the church was particularly pleasing to the prisoner was that, as Schoedel expresses it,

The Smyrneans had provided a hospitable environment for the activity of Ignatius . . . (Ignatius of Antioch, p. 219).

As I see it, when the interpolator changed the prisoner’s second name from ‘Hagiophorus’ to ‘Theophorus,’ he altered this letter’s inscription slightly to make the one bearing godly things refer not to Peregrinus, but to the church of Smyrna.

I submit, then, that ‘Ignatius who is also Theophorus’ was, in reality, ‘Peregrinus who is also Hagiophorus.’ And to be complete, Peregrinus went on, after his transformation from a Christian into a Cynic, to also be ‘Proteus’, the god of transformations. And for the four final years of his life, after announcing that he would depart in flames from this world, he was also—appropriately—Phoenix.

Roger Parvus

Roger Parvus

Latest posts by Roger Parvus (see all)

- A Simonian Origin for Christianity? — A few more thoughts - 2023-03-08 00:03:04 GMT+0000

- Revising the Series “A Simonian Origin for Christianity”, Part 4 / Conclusion – Historical Jesus? - 2019-03-07 00:35:19 GMT+0000

- Revising the Series “A Simonian Origin for Christianity”, Part 3 - 2019-03-06 23:57:30 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Roger, thanks for all the installments of this study. They have been most helpful. I enjoyed watching your methods–like a really good detective story. I used to wonder at the Ignatius character and how awfully pretentious he was and how strained I thought his relations with the churches must have been. The man Peregrinus as portrayed by Lucian, exactly fills the bill. (It would also be interesting to see a study of the development of church hierarchy as seen in these letters, if anything can be ascertained.)

Bob,

I briefly address the origin of monarchial bishops in the second half of the series. I first argue that the author of the letters (Peregrinus) belonged to a small and short-lived Christian community founded by the ex-Marcionite Apelles in the 140s. And I argue that the reason Peregrinus pushed for a monarchial type of bishop was that he saw it as the best way of insuring the survival of his small community.

Walter Bauer recognized the minority status of the communities addressed by the letters (although he did not identify them specifically as Apellean). He wrote:

And Bauer also recognized, again correctly in my opinion, that monarchial episcopacy was not yet firmly established in the communities addressed by the letter collection:

The author of the letters was trying to get the authority of the bishops of his church accepted as monarchial but, as Bauer convincingly shows on pages 66 – 70 of his book, there are many indications in the letters that an authority of that nature had not yet securely taken hold there.

My identification of the communities in question as Apellean can account for the situation described by Bauer. Apelleans would have been a newly formed community situated precariously between two more numerous and powerful Christian communities: the Marcionite church that Apelles had abandoned and the proto-orthodox church he had not yet embraced. . I can see no reason why Apelles, in breaking away from Marcionism, would not have retained the bishop-as-leader-of-the-community setup. But I expect that the bishops he put in place in his newly formed communities would have consisted of those most loyal to his interpretation of Christianity.So, as Peregrinus saw it, the most direct and immediate way to keep the other members faithful and prevent them from being led astray by the more impressive rivals was to prop up the authority of the Apellean bishops and urge obedience to them.

And this scenario would also explain why there is no impression conveyed by the letters that the communities addressed had much of a history. They are nowhere praised for fidelity to any belief that an earlier generation of members had handed on to them. And in praising the bishops of the communities (Onesimus, Damas, Polybius) the prisoner says not a word about any predecessors of theirs. In establishing their authority there is no appeal to apostolic succession. This fits my Apellean scenario. Apelleans had no continuous connection—-and claimed none—-to apostolic times. Marcion and Apelles held that the church had gone wrong almost from the start. They viewed their work as a work of restoration, but a restoration based largely on their understanding of Paul, his letters and his gospel–not on any unbroken tradition or succession of teachers in the past.

These then are some of the reasons I suspect the monarchial type of episcopacy began in the Apellean church. The hign degree of authority it conferred on its bishops was likely envied by the bishops of the other churches and laid claimed to in short order.

Thanks Roger,

You and Bauer have made the pieces of the puzzle come together for me.

I’ll disclose my bias. My real name is… Ignacio (Spanish for Ignatius). I owe my name to Ignacio de Loyola who, in turn, switched his name from Íñigo to Ignacio as a homage to that bishop of Antioch. How ironic it would be if the first Jesuit paid honour to an apostate… How shocking to discover that my true name could have been Peregrinus 🙂

Roger, how have your theories been received by the ‘experts’?

Ignacio who is also Gorit,

I don’t know that any experts are aware of my Ignatian theory. I’m going to try to change that but I don’t really expect success. My credentials (former Catholic priest with just a standard seminary education) would normally not be sufficient to be taken seriously by the scholarly community. But you never know for sure until you try. So my plans at the moment are to revise the first part of the theory (i.e., the Ignatians are reworked letters of Peregrinus) and to submit it to some scholarly journals. The aim of the revision will be to make that part of the theory able to stand alone without bringing in my views about Peregrinus’ particular brand of Christianity (Apellean). I also intend to get some professional help to “unconvolute” my prose.

In the Lucian says that Pereginius had lots of names, and you even proposed in another article that none of the three Lucian refers to was his given birth name. So I don’t see what you want to make this theory dependent on the idea that Ignatius was not a name this person actually went by. It could be all three names Lucian used were tied to the post excommunication phase of his career.

I think this theory would be more viable if you made it less of a conspiracy theory. The Separation of these two figures into different people was more a slow process of not wanting to mention these letter were written by a figure Lucian made a fool out of.

Turing the subject to another work of Lucian, could Alexander The False Prophet be connected to The False Prophet of the Revelation?

Hi Jared,

I don’t think that “Ignatius” was another name that Peregrinus himself adopted. As I see it, the main motivation of whoever reworked the letters was probably just to preserve and put to good use the Christian sentiments expressed in the originals. But to gain a hearing for that inspiring material he had to distance the letters from their lapsed Christian author, Pereginus, who ended his days as a Cynic, outside of the church. Keeping the name “Ignatius” in the letters — if that was one of Peregrinus’ names — would have been counterproductive.

In regard to Alexander: I’m not aware of any attempts to connect him to the False Prophet in the book of Revelation.

I think this basic theory could be true without presuming the letters changed at all.