Let’s try to make it clearer with a picture. Mark Erickson has attempted to have Joseph Hoffmann and Stephanie Fisher clarify their central argument for the historical Jesus:

“The political and religious conditions of the time of Jesus plausibly give us characters like Jesus. This is a tautology that must be confronted.”

Hoffmann attempts to clarify with this (unedited):

The poltical (sic) conditions of the time of late republican Rome give us characters like Antony and Caesar. Not characters like Sargom(sic), Elijah or Darth Vadar (sic). if (sic) then I have literary artifacts that conform to those condtions (sic) and contexts, how should they not be facors (sic) in establoishing (sic) the historicity of it. It’s basic historical process–the 1000 pound premise mythtics (sic) routiney (sic) dance past in their quest for improbable substitutes and “parallels” that explain the sources.

I think what Hoffmann means is that he gets cranky with anyone who suggests the source of the Jesus we find in the Gospels was, ultimately, not a historical Jesus and but some other mythical deity like Attis or Hercules.

I don’t think the evangelists were thinking of Attis or Hercules when they wrote about Jesus, and I don’t know many mythicists who do think like that, so as far as I’m concerned I’m not the least interested in his having a go at something that looks like a straw-man.

But let’s look at his “one airtight argument” Hoffmann has for the historical Jesus. As Stephanie expressed it:

The one airtight argument in [Hoffmann’s] piece [is] that the conditions for the existence of Jesus necessarily produce people of like description, so to choose an analogous over a known figure is non-parsimonious and tautologies are eo ipso true statements.

| Question for Steph: Steph, are you saying that Hoffmann’s argument is true because he has expressed it as a tautology? Tautology (rhetoric), using different words to say the same thing, or a series of self-reinforcing statements that cannot be disproved because they depend on the assumption that they are already correct |

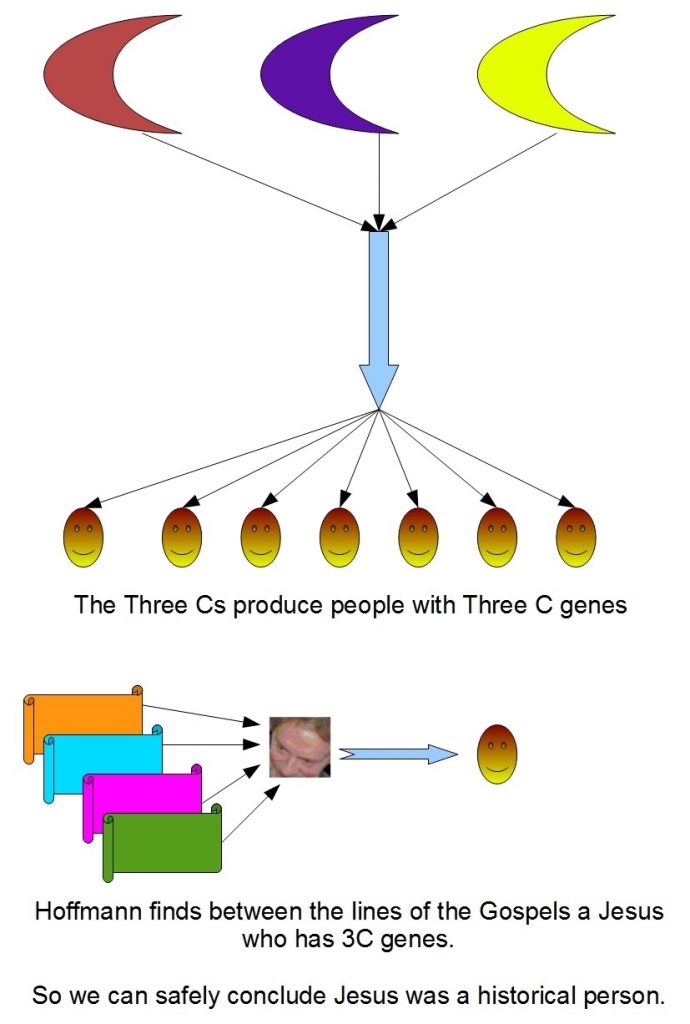

Let’s start with a graphic to try to get this clear in our heads. (See the previous post where the 3 C’s are explained: Conditions, Context and Coordinates):

Hang on! Isn’t this the same text-book fallacy we (should) know so well?

Mrs Smith’s farm produces green apples. (The 3Cs produce this type of person)

This is a green apple. (Jesus is this type of person)

Therefore this apple comes from Mrs Smith’s farm. (Therefore the 3Cs produced — historically, not just literarily — Jesus)

And that’s before we even get to finding out how Hoffmann managed to find (something like his own reflection in the Gospels and call it) Jesus with the 3C traits. (I look forward to reading how Hoffmann does that without begging the question.)

If I am wrong and am misrepresenting Hoffmann I am sure Steph or someone will let me know. . . . . Continue reading “Hoffmann’s historical Jesus argument for dummies — with a graphic to clarify it all”