The previous post covered some of the indications that the heroine of Greek novel Chaereas and Callirhoe was modelled on Ariadne of Theseus and the Minotaur fame. This post looks at the way the author Chariton has constructed his hero, Chaereas, from cuts of other mythical and legendary figures, in particular from Achilles.

The previous post covered some of the indications that the heroine of Greek novel Chaereas and Callirhoe was modelled on Ariadne of Theseus and the Minotaur fame. This post looks at the way the author Chariton has constructed his hero, Chaereas, from cuts of other mythical and legendary figures, in particular from Achilles.

Once again, of equal significance is that these fictional characters whose creation was inspired by mythical figures interact with real historical characters in the novel. This is similar to what we find in the Gospels: fictional characters and events modelled on Jewish and Greek stories interacting with historical persons such as Pilate, Caiaphas and Herod.

In the first post of this series we saw that the hero Chaereas was based on Achilles, Nireus, Hippolytus and Alcibiades. From Reardon’s translation we read in the opening paragraph of the novel:

There was a young man named Chaereas, surpassingly handsome, like Achilles and Nireus and Hippolytus and Alcibiades as sculptors portray them.

Cuevas comments:

These four men serve to illustrate the multifaceted persona of Chaereas. (p. 24 of Cueva’s Myths of Fiction)

Homer’s Iliad relates how both Achilles and Nireus fought with the Greeks in the Trojan War. Achilles was said to be the most handsome of the Greeks, while Nireus was the second-most handsome.

And Nireus brought three ships from Syme – Nireus, who was the handsomest man that came up under Ilius of all the Danaans after the son of Peleus [Achilles] – but he was a man of no substance, and had but a small following. (Iliad, 2)

So Nireus, while handsome, is flawed. He can only attract a small following.

Chariton perhaps is pointing to a dichotomy in Chaereas’s character: on the outside Chaereas may be physically strong and handsome like Achilles, but inside he is less than perfect. This dichotomy is observable in the many scenes that the handsome Chaereas either cries or opts for suicide rather than facing his problems. (p. 24)

Similarly the comparison with Hippolytus is a silver cloud with a dark lining. Hippolytus was the son of Theseus, also astonishingly handsome, who rejected the worship of Aphrodite. Aphrodite had therefore to punish him.

Likewise, Chaereas commits an outrage against Aphrodite and, accordingly, must suffer the consequences. (p. 25)

Then there is the unexpected comparison with Alcibiades. All the other comparative figures are mythological. Alcibiades is historical. He was reputed to have been handsome, but he was also infamous for his self-centred and rakish life-style.

It may be that although Achilles, Nireus, and Hippolytus are much better models than Alcibiades, Chariton, in keeping with the historical veneer of his work, includes Alcibiades, a historical figure, because the background of his novel is historical rather than mythical.

The comparison to Achilles is positive, but the other three comparisons have negative qualities . . . . Chariton delineates his character’s qualities by likening him to legendary or mythological heroes who adumbrate a likeable but faulty character. (p. 25)

Chariton draws heavily on Homer’s epics by adapting lines and motifs from the Iliad in his own novel.

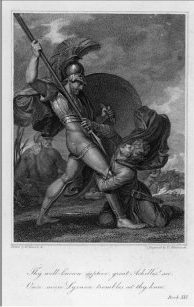

One line that Chariton repeats throughout the novel is one that is taken from the cruel moment when Achilles slays Lycaon (Iliad, 21:114)

λύτο γούνατα καὶ φίλον ἦτορ = knees were loosened and his heart was melted

Again from Reardon’s translation of Chariton’s novel, at the moment when Callirhoe is told she is to be married, thinking she is to be married to someone she did not know,

And then he limbs gave way, her heart felt faint.

Chariton’s line was well known from Homer.

This line refers to the murder of Lycaon by Achilles, which ranks second in vileness only to the shameful treatment of Hector’s body. This easily recognized line foreshadowed Chaereas’s atrocious treatment of Callirhoe: she will be kicked to death (really a Scheintod). A closer examination of this line, in view of its new literary surroundings, may also hint at the adventures of Callirhoe: she will be captured, sold as a slave, and sail to islands and coastal cities. Even if Chariton does not intend the background of this line to prefigure the adventures of Callirhoe, the line itself, with its undertones of death, relentless vengeance, and cruelty, should alert the reader to its special qualities, in that it was associated with a time that should have been filled with immense joy for Callirhoe. (p. 26)

Again, just as Achilles fainted upon hearing the news of the death of his friend Patroclos, Chaereas, on hearing that Callirhoe had been unfaithful (and like Nireus unable to gather the support of his fellow suitors) also faints with Homeric allusions. Both Achilles and Chaereas lament in the dust for a considerable time.

Cueva analyzes Chariton’s use of Homeric phrases showing how their Homeric associations heightened the dramatic moments in the novel.

Cueva shows the way many details of the narrative action and character traits are taken from Homer’s epics in the earlier part of the novel, but over time the Homeric allusions become merely decorative.

Callirhoe’s dream in which she sees Chaereas coming to talk to her is based on Achilles’ dream in which he sees his close friend Patroclos speak to him. But there are many scenes of trials and tribulations in which Homeric textual and character allusions abound.

I wonder if some biblical scholars who have very harshly judged Dennis MacDonald’s study of Homeric allusions throughout the Gospel of Mark would be so severe in their rejections of links between a Greek “historical novel” and Homer.

Analysis of Chaereas and Callirhoe shows that Chariton wrote a work with a predominantly historical background. The mythical element, however, is sizable, and cannot be disregarded. It takes many forms, such as allusion, quotation, and simile. One might even say that the social and historical conditions have a mythical quality about them. For example, women are included in assemblies, a woman conquers a barbarian king, and altogether too much importance is awarded to the demos.

The use of myth in Chaereas and Callirhoe is primarily limited to the depiction of character through mythological comparison.

Thus Callirhoe is compared to Aphrodite, Helen, the nymphs, Medea and Ariadne.

The last of the mythological analogues [Ariadne] is very important, because Chariton uses the adventures of Ariadne to direct parts of the action of the plot. (p. 33)

Chaereas is modelled on Achilles, Nireus, Hippolytus and Alcibiades. In the first half of the novel Chaereas’s character is revealed as one not up to the standard of the best qualities of a hero. But in the second half his character is explored more deeply.

In the second half of the novel the author depicts Chaereas’s character more through his acts than through mythological reference. In fact, historical characters displace the mythological as models for Chaereas.

In the second part of the novel Chaereas’s and Callirhoe’s adventures bring them face to face with the “historical” king Artaxerxes and his wife. I use quotation marks for historical because though Artaxerxes was a figure of history, his portrayal in the novel is, of course, really literary. In the same way one can say that the historical Pilate and Herod have been transformed into literary characters in the gospels. Pilate does not really act true to what is known of his historical character when he caves in to a mob calling for Jesus’ death. And Herod was very bad but we have no reason to believe he killed all the babies in Bethlehem. These are historical characters who are being bent to the requirements of a Jewish novelist(?)

Chariton’s novel is not a “gospel”. The differences are obvious and scarcely need elaborating. But there are also significant similarities that deserve attention. The gospels do have an aura of verisimilitude about them. They have historical settings and involve real historical figures. At the same time there are a number of other characters in the gospels who various scholars have argued are literary fictions (e.g. Judas, the twelve disciples, the daughter of Jairus and the son of the widow of Nain, the parents of John the Baptist, etc), some of them even based on Homeric characters (e.g. Joseph of Arimathea). Even Jesus has been compared with Moses, Elijah and Odysseus. . . . .

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- Samaria in the Persian Period - 2024-04-15 11:49:57 GMT+0000

- No Evidence Jerusalem/Judea had a “Writing Culture” in Persian times — Israel Finkelstein - 2024-04-12 09:45:34 GMT+0000

- Questioning the Hellenistic Date for the Hebrew Bible — continuing - 2024-04-11 20:54:16 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I like what you are saying in this latest series of posts. It peers into the Hellenistic cultural world of the creators of the Christ myth. Just add some Greek OT and DSS “Judaism,” stir together, and out comes Christianity. I’m still convinced that the people at History Hunters International are on the right track for finding the kind of people who could have done this. The roots are very deep, as they research the creation of divine men from Alexander the Great to Jesus and tie it all plausibly together. I don’t know if you’ve looked at the links I’ve posted, and I realize there is a ton of information on the site and you might not have time to read everything, but the nucleus of it all appears to be the “scene” surrounding Marc Antony’s daughter Atonia Minor, the Lysimachus Dynasty in Egypt, and how they brought the Flavians to power.

While I don’t agree with Joseph Atwill’s idea in Ceasar’s Messiah that Josephus and the gospels were intended to be read together and consitute a “joke” that those “in the know” would “get,” I feel that he too is generally on the right track as far the kind of people who made the gospels and the “reason” they did it.

Eisenman, too, speculated as much in JBJ. It’s interesting to think about these people. Though the roots are deep, as I said, the key time period for gospel production (at least one of them) is during the Flavian era (69-96).

Where I disagree with Atwill and HHI (and the Dutch radicals) is on the genuineness of Paul’s letters. Yes, some of them have been tampered with and some are entirely made up, but I do think the contents of some are real because they show awareness of DSS and/or “Jamesian” ideas (e.g., the three nets of Belial, things sacrificed to idols, lying, etc.). Eisenman really drives this home convincingly.

John:

Joseph Atwill’s book is so weird that it is almost unreadable. One has to agree with Prof. R.M. Price, who writes: “There are indeed surprising parallels between Josephus and the gospels that traditional exegesis has never been able to deal with adequately, but surely the more natural theory is the old one, that the gospel writers wrote late enough to have borrowed from Josephus and did so.”

Atwill does however make one interesting point, namely, that each of the gospel writers seems to have been familiar with Josephus’ writings. Several years ago, Neil discussed the striking parallels between the Passion story of Jesus Christ and the Josephus story of Jesus ben-Ananias. In 2005, Prof. Weeden argued that Mark and John had both been reading Josephus: “While in my presentation before the Jesus Seminar I did not think that Mark was dependent directly on Josephus. I now think that he was… Additional support for the likelihood that Mark got the story from Josephus, and not the reverse, is John’s dependency on the story of Jesus-Ananias which he appropriated from Josephus for his own unique depiction of Jesus’ Roman trial. If, as I argue, both Mark and John drew upon the Josephus story directly, then it is hardly likely that Josephus was dependent upon Mark and John for elements of the Jesus-Ananias’ story peculiar to their own depiction of Jesus’ trials. I cannot imagine Josephus sorting through Mark and John looking for good material to create his own story of this character…” (crosstalk2 at Yahoo). I should have liked to know whether or not Prof. Weeden has presented these latter thoughts in a peer-reviewed paper.

Michael:

A big difference between Jesus ben-Ananias and the gospel Jesus story is that in the gospel story Jesus is not set free. It’s a one time event before Pilate that leads to the crucifixion.

Actually, if one is taking a literary view of this Josephan story – then it may as well be the wonder-worker story in Slavonic Josephus that would be of interest. In that story the wonder-worker is set free – and continues his activities until a later arrest that leads to his crucifixion.

As to Jesus ben-Ananias being whipped in the Josephan story – well, history details the flogging of Antigonus after the siege of Jerusalem in 37 bc.

Jesus ben-Ananias:

…”the man, brought him to the Roman procurator, where he was whipped till his bones were laid bare……………… Albinus took him to be a madman, and dismissed him…”

Antigonus:

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/49*.html

“These people Antony entrusted to a certain Herod to govern; but Antigonus he bound to a cross and flogged,— a punishment no other king had suffered at the hands of the Romans,— and afterwards slew him.”

Angigonus is historical – Jesus ben-Ananias? Most probably a literary creation of Josephus – Josephus wearing his prophetic historian’s hat….

Michael:

Just a footnote to my last post – regarding the two arrests and on after the first arrest set free. Antigonus was twice arrested – he was not set free the first time – he escaped.

“He was the second son of Aristobulus II., and together with his father was carried prisoner to Rome by Pompey in 63 B.C. Both escaped in 57, and returned to Palestine.”

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=1580&letter=A

Creating a literary figure from historical personalities?

Have that figure crucified – by a Roman procurator, Pilate ,(stand-in for Mark Antony) at the instigation of fellow Jews (stand-ins for Herod the Great ). Antigonus ruled for 3 years – so your fictional figure has a 3 year ministry. Antigonus cut off the ears of his uncle to prevent him from every again ruling as High Priest/King. Your fictional character has one of his followers cut of the ear of a servant of the high priest. Antigonus was the last King/Priest of the Jews. Your fictional character has a notice above his cross labelling him King of the Jews – and you have him crucified after his 3 year ministry – around 33 ce – 70 years from that earlier tragic event in 37 bc. Antigonus was crucified in Antioch – and your literary story has Antioch as the place in which followers of the dead crucified figure first begin to be known by his name, followers of the anointed one.

( I don’t think Antigonus = JC of the gospels – JC is a composite literary figure reflecting more than one historical figure).

Thanks! Antigonus the Hasmonean is a fascinating character in his own right. It seems worth noticing that, according to Josephus, Antigonus was beheaded. Apparently, it was Dio Cassius who introduced the notion that Antigonus had been scourged and crucified. Even if he never mentions Christianity, the possibility cannot be ruled out that Dio Cassius’ version is influenced by the gospels.

I agree that Jesus ben-Ananias is most probably a literary creation. His message of woe against Jerusalem and the fact that he was beaten and tortured are reminiscent of Jeremiah.

You wrote: “JC is a composite literary figure reflecting more than one historical figure…” Zacharias, the son of Baris (see Josephus, Jewish War 4.334-344) is yet another figure who may have provided elements for the construction of Jesus; cf. J.B. Gibson, “The Function of the Charge of Blaphemy,” in: G. Van Oyen, T. Shepherd, eds, The Trial and Death of Jesus (Peeters, 2006). According to Gibson, “it seems difficult to escape the conclusion that Mark has cast his story of Jesus’ Sanhedrin “trial” and condemnation so as to call to mind the Zealot trial and condemnation of Zacharias” (p. 186).

Michael: “Thanks! Antigonus the Hasmonean is a fascinating character in his own right. It seems worth noticing that, according to Josephus, Antigonus was beheaded. Apparently, it was Dio Cassius who introduced the notion that Antigonus had been scourged and crucified. Even if he never mentions Christianity, the possibility cannot be ruled out that Dio Cassius’ version is influenced by the gospels. “

Or Josephus has his own reasons to only record the beheading of Antigonus – and Dio Cassius has caught him out! If there were Roman records – then Dio Cassius probably had access to them. Josephus can do his nut re his Jewish prophetic interpretations – but he was not able to rule the roost with Roman history. Just think about it. If Josephus had recorded the scourging and crucifixion of Antigonus – the connection with the gospel storyline is easily discerned.

Michael: “I agree that Jesus ben-Ananias is most probably a literary creation. His message of woe against Jerusalem and the fact that he was beaten and tortured are reminiscent of Jeremiah.”

And the dating – 63 ce is 100 years back to 37 bc and the death of Antigonus by the Roman Mark Antony. Quite a historical moment for someone interested in replaying the historical tape – as I think Josephus is often doing. Sure, dress up Jesus ben-Ananias as some sort of madman – but the 100 year anniversary of the end of the Hasmonean rule is particularly noteworthy as a date upon which to connect Jesus ben-Ananias. The 37 bc siege of Jerusalem, by some accounts, was around 5 months – and Josephus is making Jesus ben-Ananias preach woe for 7 years – and 5 months. (and Josephus, himself, or whoever is writing under than name – claims Hasmonean decent…)

Thanks for the book references. I don’t think, in trying to understand the gospel storyline, that one can just consider the short 3 years given (gJohn) for the ministry of Jesus. One has to consider earlier history – and one is free to do that once one has decided for a non-historical Jesus figure. Luke 3.1 can be spread out – back to Lysanias of Abilene in 40 bc. (Also, of course, the year in which Antigonus became King/High Priest in Jerusalem). A 70 year period of Jewish history. A period that saw the end of the Hasmonean King/Priests, ie the end, the terrible end of the last King of the Jews, Antigonus. It’s not just history one is after of course, it’s a particular history – the history of early Christianity. And if the gospels, in the creation of their main literary figure, are showing an interest in using Hasmonean history – then that does indicate that the early Christian writers found some relevance in it for their salvation history interpretations. Which leads to the question of Why?

(just as a side note – Antigonus produced bilingual coins, Greek and Hebrew. King Antigonus in Greek and Matisyahu the High Priest, in Hebrew – and that gospel Jesus figure – well its a trilingual sign over his cross – King of the Jews in Aramaic, Latin and Greek.)

Michael:

I agree. I only mentioned his book because he talks about Antonia Minor et al. I don’t like the book otherwise and I don’t buy what he’s selling.

Neil:” In the same way one can say that the historical Pilate and Herod have been transformed into literary characters in the gospels. Pilate does not really act true to what is known of his historical character when he caves in to a mob calling for Jesus’ death. And Herod was very bad but we have no reason to believe he killed all the babies in Bethlehem. These are historical characters who are being bent to the requirements of a Jewish novelist(?)”

Pilate, according to Philo was a corrupt Roman official.

http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book40.html

ON THE EMBASSY TO GAIUS

“But this last sentence exasperated him in the greatest possible degree, as he feared least they might in reality go on an embassy to the emperor, and might impeach him with respect to other particulars of his government, in respect of his corruption, and his acts of insolence, and his rapine, and his habit of insulting people, and his cruelty, and his continual murders of people untried and uncondemned, and his never ending, and gratuitous, and most grievous inhumanity. (303)

According to Slavonic Josephus, Pilate caved in to the “teachers of the Law” when they bribed him with the 30 talents to have the wonder-worker crucified.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/chr/gno/gjb/gjb-3.htm

26. “The teachers of the Law were [therefore] envenomed with envy and gave thirty talents to Pilate, in order that he should put him to death. 27. And he, after he had taken [the money], gave them consent that they should themselves carry out their purpose.”

The gospels have Pilate caving in to the Jews – but forget to mention the bribe in the Slavonic Josephus storyline – why? Well, the gospels are wanting to have Judas in the role of betrayer for the 30 pieces of silver. The change of direction, the developing storyline, consequently, leads to a picture of Pilate as a weak character in the gospels….

Regarding Herod the Great and the slaughter of innocents. History places this not in Bethlehem but at the Herod’s siege of Jerusalem in 37 bc.

“….so they were murdered continually in the narrow streets and in the houses by crowds, and as they were flying to the temple for shelter, and there was no pity taken of either infants or the aged, nor did they spare so much as the weaker sex….yet nobody restrained their hand from slaughter, but, as if they were a company of madmen, they fell upon persons of all ages, without distinction.’ Ant. Book XIV ch.XVI. 1

Re the gospel Judas story: One could go a step further: Pilate takes the 30 talents from the teachers of the Law, which leads to the wonder-worker crucified in Slavonic Josephus. Judas takes the 30 pieces of silver from the priests, which leads to the crucifixion of the gospel Jesus. In history, Mark Antony takes a ‘great deal of money’ from Herod the Great in order to crucify and behead Antigonus, the last King/Priest of the Jews, in 37 bc. (Ant.16.4)

“Out of Herod’s fear of this it was that he, by giving Antony a great deal of money, endeavored to persuade him to have Antigonus slain, which if it were once done, he should be free from that fear”. (Ant.16.4)

Wikipedia: Antigonus II Mattathias

Footnote: “Josephus merely says that Marc Antony beheaded King Antigonus. Antiquities, XV 1:2 (8-9). Roman historian Dio Cassius says scouraged, crucified then put to death. See The University Magazine and Free Review, Volume 2 edited by John Mackinnon Robertson and G. Astor Singer (Nabu Press, 2010) at page 13. Merging the material from Josephus and Dio Cassius leads to the conclusion that Antigonus was scourged, crucified, and beheaded.”

Methinks the gospels are a little bit more than novels – albeit much within them is of a literately nature. Salvation history interprets history, it seeks out some meaning or other, some relevance. A great Jewish pastime – which if it’s early Christian origins we are after, we need to pay some attention to. It’s not simply a case of Paul’s Christ figure being historicized ie given a literary pseudo-history in the gospels. It’s rather a case, with the gospels, of history being interpreted from a salvation scenario. Salvation history is history scripturalized. Working from Paul is only getting one to a literary pseudo-history; Paul’s spiritual construct historicized – from which history cannot be discerned. Working from history can provide a way into the gospel interpretation of it. Don’t, say the mythicist, read the gospels into Paul. Then the other way around must also have value – don’t read Paul into the gospels. Treat both stories separately until one can discern where they can be ‘fused’, where they can be seen to be complementary instead of contradictory.

I think the name of this genre is historical fiction. I had a period where I devoured everything I could find about about antiquity in this genre, certain standouts being Julian by Gore Vidal and Raptor by Gary Jennings. Both mix real people and events with fictional ones. In these cases the main point is to entertain and not to “deceive,” but the genre can be used for whatever purpose, I suppose. In Julian, surely Vidal wants you to think that Julian was “cool” guy. In the case of the gospels I feel the point is to undermine/claim/absorb messianic Judaism for Rome.

JW:

In my related Thread at FRDB:

http://www.freeratio.org/showthread.php?t=262303

“Wrestling With Greco Tragedy. Reversal From Behind. Is “Mark” Greek Tragedy?”

I just linked to this post. The ancient technique of using elements of settings from previous famous works is a clear Marker of Fiction. This is the type of criterion that Burridge should have to help distinguish ancient genre, known fictional styles.

Joseph

“Chariton draws heavily on Homer’s epics by adapting lines and motifs from the Iliad in his own novel.”

It sounds like what we are saying is that Chariton is engaging in Greek “midrash”. Are there any good studies of this kind of exegesis in the pagan world?

The term generally used to refer to the use and adaptation of lines and motifs from other literature is intertextuality. Midrash has a wider range of meanings and applies to Jewish theological writings. Yes, intertextuality is a well-known literary practice among the ancient writers of the time we are interested in. We have ancient texts discussing writing practices (Aristotle’s being the best known) such as these. Dennis MacDonald also refers to these discussions in his book on Mark and Homer, and Thomas Brodie likewise discusses the methods, with examples, at some length in his Birthing the New Testament.